第54話(2023/1)

‘Hiharin’

in 1940s South Uist: A Remnant of an Earlier

Tradition?

パイプのかおり

第52話の David

Murray の文章の中で触れられていた、Joshua

Dickson の 記事です。彼のエジンバラ大学に於ける博士論文の一部との事。

パイプのかおり

第52話の David

Murray の文章の中で触れられていた、Joshua

Dickson の 記事です。彼のエジンバラ大学に於ける博士論文の一部との事。1940年代の Sout Uist 島のパイパーが演奏していたピーブロックの 'hiharin' に、オールド・スタイルの痕跡が残っているのは、果たして Sout Uist 島でピーブロック伝承の脈が途切れず続いて来たのか、それとも、いずれかの時点で、外から入って来た痕跡なのか? と言った内容。お楽しみ下さい。

| 原 文 |

日本語訳 |

|---|---|

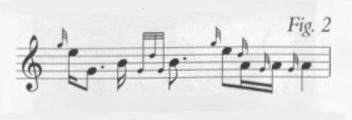

| According to living

memory, very few individuals in South Uist

displayed practical knowledge of ceol mor

in the years leading up to the twentieth

century. It is commonly held by piping

authorities that the classical form completely

died out in the Hebrides with the decline of

musical patronage in the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, and that it was

re-introduced to the South Uist community with

spectacular and long-lasting effect by the

Piobaireachd Society who sent instructors from

1909 to 1958. This is true to an extent, in that it was re-introduced from outside on a largescale, organised basis, but the idea that ceol mor had totally evaporated from the community by then is difficult to accept when considering that South Uist had been regarded by folklorists throughout the previous fifty years as the last great storehouse of Gaelic tradition. There is evidence from oral and written sources that challenges the notion. Local pipers remembered nowadays as having played it before the arrival of the Piobaireachd Society include Lachlan MacCormick, Neil Campbell (father of Angus Campbell of Frobost) and William MacLean, the last having won the Inverness gold medal in 1901 and that of Oban in 1912. However, MacLean cannot rightly be considered as a bearer of any specific Uist tradition because he was an incomer from Mull and learned ceol mor from Calum Piobair in Badenoch. The case of MacCormick presents another difficulty: although a native of Benbecula and a very successful competitor in both ceol mor and ceol beag around the beginning of the century, contemporary reports in the Oban Times show that ceol mor was not played in competition in South Uist prior to 1908 ; therefore, what it claimed in oral tradition can not be verified by written records. Despite these difficulties, oral tradition asserts that ceol mor was indeed known and played in South Uist before the involvement of the Piobaireachd Society and this is supported by several points. Lachlan MacCormick was known to play settings of tunes in competition which conflicted with the Society’s, and there is no reason to doubt that he learned them within the Uist community rather than, say, in the Army where tuition was by Society instructors. Furthermore, Neil Campbell of Frobost is reputed to have been taught ceol mor by a family of MacGillivrays who leased land in Eoligarry, Barra, in the early 1880s. Additional (if ambiguous) support is found in the military record of Neil Maclnnes, a native of South Uist who enlisted in the Cameron Highlanders in 1889; appointed Piper in the 1st Battalion in 1892, he took second place in ceol mor at the regimental games in Malta in 1893 and first place in 1896. This is inconclusive, however, in that he may have learned ceol mor in the army rather than in Uist. The memoirs of Frederick Rea, an English Catholic schoolmaster in Garrynamonie from 1890 to 1913 provide further glimpses of a pre-twentieth century ceol mor tradition. He observed that the now-legendary parish priest of Eriskay, Fr. Allan McDonald, was a great lover of the piping arts and would often hold ceilidhs in his own kitchen, inviting others to dance to the pipes while he preferred to stand aside and, in his own words, “bask in the heat of the reel”. Among the local pipers who would regularly play for Fr. Allan who, one should note, died four years before the Piobaireachd Society split their first instructor ー Rea remembered a “peculiar looking man with almost lint-white hair, smooth hairless face, was of squat figure and spoke no English. There was no doubt about his ability as a piper. His speciality was the piobaireachd, and as he played the others seemed to listen to him in awe ー I believe that he read and wrote music for the bagpipes and was him self a composer.” By far, however, the most compelling evidence of a pre-Kilberry tradition, of ceol mor performance in South Uist comes from Calum Beaton, a highly-regarded piper from Stoneybridge whose first lessons in ceol mor were by a man from a neighbouring township in the late 1940s. Calum’s father was a piper, but he had refused to teach his son the pipes because he himself had learned by ear - as did the vast majority of pipers of his generation in South Uist - and he felt that he was ill-qualified in the new era of competition and literacy. Calum turned instead to an older cousin, an army piper who had recently returned home from the war, but, as it turned out, this did not last long. Calum remarked (translated from Gaelic) : “The man who I had for teaching, Alasdair Beaton, said that he didn’t know how to play ceol mor, and he asked me to go to another man, John Archie MacLellan, who stayed in the next township ... I went to him and he said that he didn’t play much at all he knew two or three. He gave me a ‘Lament for Mary MacLeod’ and ‘Lament for Patrick Og MacCrimmon’. He gave me a different style ... I thought that it was the correct way, and I played it like that.” John Archie MacLellan was taught by one of the Smiths of Howmore, a well-known Uist piping family who in turn may have been taught by pipers either from Eochar or Barra in the late nineteenth century. In these two tunes, he taught Beaton to play the ‘hiharin’ movement, or the ‘pibroch birl’, in a very different way than was then, and is now, heard in mainstream competition performances ; a way which in fact recalls an eighteenth, and early nineteenth-century, style which appears to have gone largely out of fashion between the publication of Angus MacKay’s Ancient Piobaireachd (1838) and the Piobaireachd Society’s second series of tune collections which began in 1925. Contemporary notation suggests that in the former time period, ‘hiharin’ comprises a pulse on the low A note followed by a division of the A by two low G gracenotes in quick succession ; the whole of the movement making, apparently, two distinct beats. The A would invariably be introduced by a cadence of short G- E-D gracenotes, such as in Donald MacDonald’s setting of ‘Patrick Og’ in his published collection, c. 1820. Shown below is the last bar of line 1 of the ground: |

20世紀までの South Uist

に於いては、ピーブロックに関して実践的な知識を持っていた人はほとんど居なかった、と言われている。18世紀から19世紀にかけての音楽的パトロンの衰

退とともに、ヘブリディーズ諸島では古典的な形式が完全に消滅し、1909年から1958年までの間、

指導者を派遣していたピーブロック・ソサエティーによって、華々しくかつ長期にわたって South

Uist のコミュニティに再導入された、とパイプの専門家は一般的に考えている。 これは(ピーブロックの演奏文化が)大規模かつ組織 的に外部から再導入されたという点ではある程度正しいが、それまでの 50年間、民俗学者たちにとっては、South Uist がゲール語伝統の最後の大貯蔵庫として認識されていたことを考えると、それまでにピーブロックがコミュニティから完全に消滅したという考え方は、受け入れ がたいものである。 口承や文書による資料から、この考え方に疑問を投げかける証拠がある。 今日まで記憶されている、ピーブロック・ソサエティーが到来する前に演奏していたとされる地元のパイ パーには、Lachlan MacCormick、Neil Campbell(Frobost の Angus Campbell の父)、William MacLean がおり、最後の一人は1901年に Inverness のゴールドメダル、 1912年には Orban のゴールドメダルを獲得している。しかし、MacLean は Mull島からの移住者で、Badenoch の Calum Piobair からピーブロックを学んだため、Uist 独自の伝統を受け継ぐ者とは言えない。 MacCormick の場合は、もう一つの難点がある。Benbecula 島出身で、20世紀初頭にはピーブロックとライトミュージックの両方で大成功を収めたが、オーバン・タイムズ紙によると「1908年以前には South Uist でピーブロックが競技として演奏されたことはない。」とされている。したがって、口頭で伝わって来た言い伝えを、文字の記録として検証することができな い。 このような難しさにもかかわらず、言い伝えでは「ピーブロック・ソサエティーが関与する以前に、 South Uist でピーブロックが実際に認知され演奏されていた。」と伝えられていて、いくつかの点からも裏付けられている。 Lachlan MacCormick は、 コンペティションに於いてソサエティーの推奨するセッティングと相反するセッティングを演奏したことが 知られており、彼がソサエティーのインストラクターが指導する陸軍ではなく、Uist のコミュニティーの中で学んだ事を疑う理由はないだろう。 更に、Neil Campbell of Frobost は、1880年代前半に Barra 島の Eoligarry に土地を借りていた MacGillivray 家からピーブロックを教わったと言われている。1889 年にキャメロン・ハイランダーズに入隊した South Uist 出身の Neil Maclnnes の軍歴にも(曖 昧ながら)裏付けがある。彼は、1892年に第1大隊のパイパーに任命され、1893年に Malta で行われた連隊によるハイランド・ゲームのピーブロック部門の2位、1896年には1位を獲得してい る。 しかし、彼は Uist ではなく陸軍でピーブロックを学んだ可能性があるため、この点については結論が出せない。 1890年から1913年まで Garrynamonie に滞在した英国人カトリック校長 Frederick Rea の回想録から は、20世紀以前のピーブロックの伝統をさらに垣間見ることができる。 彼は、今では伝説となっている Eriskay の教区司祭、Allan McDonald 牧師がパイピン グ芸術の大ファンであり、しばしば自宅のキッチンでケイリーを開催し、友人たちを招いてパイプに合わせ て踊る一方で、自分は脇に立って、彼自身の言う所の「リールの熱に浴する」ことを好んでいたと述べてい る。Allan 牧師のもとで定期的 に演奏していた地元のパイパーの中で、Rea はピーブロック・ソサエティーが最初の講師を派遣する4年前に亡くなった「ほとんど糸くずのような白い 髪で、毛のない滑らかな顔、ずんぐりした体型で、英語を話さない奇妙な男」を覚えていた。彼のパイプ奏 者としての才能は疑う余地がなかった。彼の得意技はピーブロックで、彼が演奏すると、他の人たちは畏敬 の念を持って彼の演奏に耳を傾けていたようだ。彼はバグパイプのための音楽を読み書き出来て、彼自身も 作曲家であったと信じられる。 しかし、South Uist にキルベリー以前にもピーブロックが演奏されていた伝統があることを示す最も有力な証拠は、Stoneybridge 出身の高名なパイパー、Calum Beaton が1940年代後半に隣町の男性から初めてピーブロックを習ったというものである。 Calum の父親はパイパーだったが、息子にパイプを教えることを拒んだ。な ぜなら彼自身は、South Uist の同世代のパイプ奏者の大多数と同じように、耳で学んでいたため、コンペティションへの対応と読み書きの能力が求められる新しい時代に、自分は指導者とし て不適格だと感じたのであ る。Calum は 代わりに、最近戦争か ら帰ってきた、陸軍のパイパーであった年上の従兄弟を頼ったが、結果的にそれは長くは続かなかった。 カルムは次の様に語った(ゲール語から翻訳)。 「Alasdair Beaton はピーブロックの演奏方法を知らないと言い、隣の町に住む John Archie MacLellan のところへ行くようにと言いました..。私は彼のところへ行きましたが、彼はたいした演奏はできないと言いつつ、2つか3つは知っていると言いました。彼 は私に "Lament for Mary MacLeod" と "Lament for Patrick Og MacCrimmon" を教えてくれました。彼は私に違うスタイルを教えてくれていたんだ....。私はそれが正しい方法だと思って、そのように演奏しました。」 John Archie MacLellan は、Uist の有名なパイピングファミリーである Smiths of Howmore の一人から教えを受け、その後 19世紀後半に Eochar か Barra のパイパーから教えを受けたと思われる。 この2曲で、彼は Beaton に 'hiharin' ムーブメントや 'pibroch birl' を、当時や現在の主流のコンペティションで聴く事ができるそれらとは全く異なる演奏方法で教えた。この演奏方法は、実際、Angus MacKay の Ancient Piobaireachd(1838年)の出版と1925年に始まった ピーブロック・ソサエティーの第2シリーズの曲集の間にほとんど流行らなくなったような、18世紀、 19世紀の初期のスタイルを思い起こさせる。 現代の表記法から推測すると、以前の時代には、'hiharin' は、"low A" のパルスに続いて、"A" を2つの "low G" の装飾音で分割し、素早く連続させたもので、この動き全体で、明確な2ビートを形作っていた。 "A" は、1820年頃に出版された Donald MacDonald Book の "Patrick Og" のセッティングに見られるように、必ず短い "G-E-D" によるカデンツのイントロを伴うことになる。下図は、この曲の1行目の最後の小節である。 |

|

|

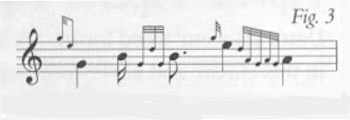

| MacKay’s publication eighteen

years later, however, represents the

introductory E in general as having greater

value. Whether MacKay’s notation in this

instance reflects a dif ferent style that

MacDonald’s, or sim ply a different way of

depicting the same style, is an ongoing debate

; but in the case of the ‘hiharin’, one

can clearly see that it absorbs some of the

value of the themal A: |

しかし、18年後に出版された MacKay の表記法の方が、イントロ

"E" の値が大きい事を表している。この場合の MacKay

の表記が、MacDonald と

異なるス タイルなのか、それとも同じスタイルを異な

る方法で表現したに過ぎないのかは、現在も議論が続いているが、‘hiharin’

の場合、テーマ音である "A" の値の一部を吸収していることがよく分かる。 |

|

|

| Representations of the

introductory E’s value would become greater

still in the early twentieth century under the

editorship of the Piobaireachd Society, who

based many of their settings on MacKay’s. Their version of ‘Patrick Og’ was published in Book 3 of their second series (1930); notice how the E of the ‘hiharin’ has become essentially equal in value to the themal A, taking up the whole of the first beat, while the As division is compressed into a run of short gracenotes as a result: |

イントロ "E" の大きさは、20世紀初頭、MacKay のセッティングを

多く取り入れたピブロック・ソサエティー版の楽譜の中で、さらに大きくなって いくことになる。 彼らのバージョンの "Patrick Og" は、ピーブロック・ソサエティー・セカンド・シリーズの Book3(1930年)に 収められていて、'hiharin' の "E" がテーマ音の "A" と同じ値になり、1拍目全体を占めるようになり、その結果、次の様に複数の "A" が短い装飾音に圧縮されていることに注目。 |

|

|

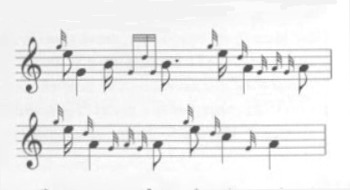

| I do not mean to suggest by

these examples that the ‘hiharin’ motif’s

evolution over the course of a century was

entirely linear and universal ; only that,

due to the priority given to MacKay’s settings

in competition and their later adoption by

Society editors, by about the 1920s the motif as

depicted in Figure 3 had become standard in

mainstream performance. Other publications such as General C.S. Thomason’s Ceol Mor (1900) and Lt. John MacLennan’s Piobaireachd as MacCrimmon Played It (1907) discuss styles of‘hiharin’ whose emphasis, like Donald MacDonald’s, favour the A; but these were written from the point of view of those marginalised by the predominance of the MacKay - Piobaireachd Society method. Calum Beaton recorded for me on the practice chanter the ‘hiharin’ movement as he’d learned it from John Archie MacLellan. In both ‘Patrick Og’ and ‘Mary MacLeod’ the emphasis was firmly on the initial low A, with the introductory E receiving greater value than a gracenote, but less than a full themal note; while the second of the divided As was played as quickly as a gracenote: |

これらの例から、1世紀にわたる 'hiharin'

モチーフの進化が完全に直線的で普遍的であったと言いたいわけではない。ただ、コンペティションで MacKay のセッティングが

優先され、後にピーブロック・ソサエティーの編集者が採用したことにより、1920年代頃に

は図3のようなモチーフが主流な演奏の標準となったということである。 General C.S. Thomason の楽譜集 "Ceol Mor" (1900) や Lt. John MacLennan の "Piobaireachd as MacCrimmon Played It" (1907) などの他の楽譜集は、Donald MacDonald のように "A" を強調した 'hiharin' のスタイルについて述べているが、これらは MacKay - Piobaireachd Society のメソッドの優位 性から疎外されていた 人々の視点から書かれたものであった。 Calum Beaton は John Archie MacLellan から習った 'hiharin' の動きを練習用チャンターで録音してくれた。 "Patrick Og" と "Mary MacLeod" では、最初の "Low A" にしっかりと重点を置き、イントロ "E" は装飾音よりは大きな大きな重さだが、テーマノートよりは軽く、分割された "A" の2番目の "A" は装飾音と同じくらい早く演奏された。 |

|

|

| One can see from the above that

in Beaton’s playing, the two beats of ‘hiharin’

are fulfilled by the themal A as in the manner

depicted by Donald MacDonald in 1820 or, to take

it fur ther, by Joseph MacDonald in 1760. Shown

in this context, such an anachronism suggests

several things: first, that ceol mor survived to an uncertain extent among South Uist pipers in the pre-Piobaireachd Society era; second, that at least some local pipers performed in an older style than that which was commonly played in mainstream circles; and third, that transmission of this style, or at least a remnant of it in the form of the ‘hiharin’, continued among a few families or individuals until well after the piping community’s initial exposure to mainstream influences. Of course, there is room for doubt. By Beaton’s time, other styles of‘hiharin’ had been in print for decades (such as in the works by Thomason and MacLennan above) and there is no way to know, at this point, whether John Archie MacLellan or the Smiths before him had not come upon such publications themselves or been influenced by players outwith Uist who had. Indeed, the quick division of low A in the ‘hiharin’ as it appears in MacLennan’s Piobaireachd As MacCrimmon Played It (1907) is strikingly similar to Beaton’s method. But the idea that the South Uist commu nity’s conservative nature was tena cious enough to retain a fragment of old-world ceol mor for so long, and under such pressure from conflicting influences, is a tempting one. I believe that Beaton’s testimony, combined with the other indications presented above, makes a strong case for it. As an epilogue I should mention that shortly after his lessons with MacLellan, Beaton went to Angus Campbell, the star pupil of the Piobaireachd Society courses in the earlier years of the century. According to Beaton, Campbell firmly pointed out that the ‘hiharin’ as he had learned it was “old-fashioned”, and intro duced him to the Kilberry style we all know today. He never played the older style in public again. |

以上のことから、Beaton

の演奏では、1820年の Donald

MacDonald、あるい は1760年の Joseph MacDonald

が描いたように、 'hiharin' の2拍がテーマ音 "A"

で満たされていることがわかる。この文脈で示されるこのようなアナクロニズムは、いくつかのことを示唆している。 第1に、ピーブロック・ソサエティー以前の時代、South Uist のパイパーたちの間でピーブロックが不確かな程度に生き残っていたこと、 第2に、少なくとも一部の地元のパイパーたちは主流派でよく演奏されていたスタイルよ りも、古いスタ イルで演奏していたこと、 第3に、このスタイル、あるいは少なくとも 'hiharin' という形での名残りが、パイピング・コミュニティがメインストリームの影響に最初に触れたずっと後まで、数家族または個人の間で続いていたということであ る。 もちろん、疑う余地もある。 Beaton の時代には、他のスタイルの 'hiharin' が何十年も前から印刷されており (上記の Thomason と MacLennan の楽譜集など)、John Archie MacLellan や Smiths 一族 以前の人々が、自らそのような楽譜集に出会わなかったか、或いはそれらを持っていた Uist 以外のプレイヤーから影響を受けていなかったか、この時点で知るすべはないのである。 確かに、MacLennan の Piobaireachd As MacCrimmon Played It (1907)に出てくる 'hiharin' の "Low A" の素早い分割は、Beaton の方法に驚くほど似ている。 どうであれ、South Uist のコミュニティーの保守的な性格が、相反する影響から受ける圧力の中で、古い世界のピーブロックの断片を長い間保持するほど粘り強かったという考えは、魅 力的なものである。Beaton の証 言は、先に述べた他の証拠と合わせて、それを強く立証するものであると思う。 エピローグとして、MacLellan のレッスンを受けた後、Beaton は 今世紀初頭の ピーブロック・ソサエティー・コースのスター生徒であった Angus Campbell のところに 行ったことを述べておくことにする。 Beaton に よると、Campbell は彼が習っ た 'hiharin' が「時代遅れ」であることをしっかりと指摘し、今日私たちが知っているキルベリー・スタイルを紹介した とのことである。その後、Beaton は 2度と人前で古いスタイルを演奏することはなかった。 |

| This article is based on a portion of Chapter 5 of my PhD thesis, The Piping Tradition of South Uist, University of Edinburgh, 2001. | この記事は、私の博士論文、The Piping Tradition of South Uist, University of Edinburgh, 2001の第5章の一部に基づいてい ます。 |