第46話(2022/11)

Changing Styles in Pibroch Playingby Dr. Peter Cooke

"International Piper" Vol.1/No.2-1978/6&Vol.1/No.3-1978/7

2022年11月2日付け音 のある暮らしのコーナーで 書いた様に、1978年5 月号〜1981年10月号に発刊されていた "International Piper" の発行の趣旨が見えて来ました。その趣旨に沿ってピーブロック関連記事のトップバッターとして、No.2とNo.3 に連載された、Dr. Peter Cooke によるタイトル記事を紹介します。非常に示唆に富んだ内容です。

なお、この記事は 2022年9月の NPCアーカイブ(PDF版)開設に先立っ て、2020年4月の Bagpipe News にテキスト自体がデジタル化された記事として公開されています。英文だけを読む場合はそちらの方が読み易いと思い ます。

| 原 文 |

日本語訳 |

|---|---|

| Cadence E's and Beats on A.

Part1 【Vol.01/02-1978 /6】/Bagpipe News on April 1, 2020 |

|

| The pibroch

repertory must be the only musical repertory in

the world that survives virtually solely in the

context of official competitons. The opinion of many pipers about this seems to be that competitions are a necessary evil — for without them a fascinating repertory would no longer be heard but instead be known only as curious fragments preserved on paper in libraries and museums. As things stand in the 1970s the frequency of pibroch competitions, the large numbers of competitors and the number of different pieces that are offered up at these competitions suggest that the newly-formed Highland Society of London made a sensible decision when it planned that first competition at Falkirk in 1781. On the face of things it appears that a musical style, which before the 18th century flourished in the castles and houses of Gaelic chieftains, on their battlefields and in their glens, has as a result been faithfully preserved unchanged down to the present. |

ピーブロックのレパートリーは、世界で唯

一、 事実上公式のコンペティションでのみ存続している音楽レ パートリーであるに違いない。 この点については、多くのパイパーがコンペティションは必要悪であると考えているようで あ る。なぜなら、コンペティションがなければ、魅力的なレパートリーはもはや聴くことができず、図書館や博物館 に保存されている紙の上の不思議な断片としてのみ知られることになるからだ。 1970年代の現状に於ける、ピーブロック・コンペティションの開催頻度、参加者の多さ、コンペティ ションで演 奏される曲目の多彩さを見れば、当時新たに結成された Highland Society of London が、1781年に Falkirk で最初のコンペティションを企画した事は、賢明な判断だったと言えるだろう。 一見すると、18世紀以前にゲールのチーフテンの城や家、戦場や峡谷で繁栄した音楽スタイルが、結果 として現在まで変わることなく忠実に保存されているように見える。 |

|

TRADITION CHANGES

But has it? A musicologist will expect such an answer to be always "no”, and for many the study of musical change within a culture (in response to internal innovation or changing social context, or to influences from outside) is a study of absorbing interest in itself. Anyone who considers that the pibroch tradition is an exception to this should read the Piping Times of November 1976 where the editor referred to the pibroch playing of P.M. William MacLean — one of the champion pipers of the beginning of this century ー as now being of purely academic interest. Or they should take a look at piping correspondence in back copies of the Oban Times, where in the early years of this century each new issue of collections of pibrochs gave rise to indignant and often lengthy letters or reviews concerned with what their writers saw as changes for the worse in the notating and playing of the music. Some of these protests no doubt stemmed from a failure to admit that just as there are even today different dialects of Gaelic spoken throughout the Gaeltachd, or different traditional singing styles, so there must have been different performance traditions in pibroch playing, each with entirely reasonable claims to validity. In a non-competitive situation there is often tolerance of,and sometimes positive interest in differences in performance style. Sometimes this is also true of the competition context. The annual traditional singing competition organized at Kinross each September by the Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland is a particularly happy example. Several years ago the organizers accepted that it is impossible to have a yardstick for judging traditional singing and adopted two simple but effective measures. One was to appoint each year the winner of the competition held the previous year as one of the two judges (on the assumption that the traditional Scots singer is the best judge of what traditional Scottish singing is all about). The other was to ask the judges simply to select as the 'winner' the singer whose performance they most enjoyed, for whatever reason, and not to go beyond saying who were the immediate runners- up. In this way the principal aims of the organisation, namely to encourage and provide a platform for the performance of traditional Scottish music, was achieved without allowing the competitive spirit to rule supreme. |

伝統は変化する

しかし、本当に伝統は変化してないのだろうか。音楽学者であれば、そのような答えは常に「否」であ ると考えるだろう。そして、多くの人にとっては、ある文化の中での音楽の変化(内部の革新や社会的背景の変化、外 部からの影響に対応したもの)は、それ自体が非常に興味深い研究対象だと言えよう。 ピーブロックの伝統についてはだけ例外的である、と考える人は、1976年11月号の Piping Times を読んで欲しい。編集者は、今世紀初頭のチャンピオン・パイパー である P.M. William MacLean (リード文右写真のパイパー/クリックで関連記事にリンク)の ピーブロック演奏について、現在は純粋に学術的な興味しかないと言及している。 また、Oban Times のバックナンバーの読者投稿欄を見るべきだろう。そこには、今世紀初頭、ピーブロック の楽譜集が新しく発行されるたびに、その楽譜集の執筆者が楽曲に関する音符の表記と演奏方法が改悪されている、と受け止め憤慨した読者からの長い手紙やレ ビューが度々書かれている状況が読み取れるだろう。 これらの抗議の中には、今日でもゲール語地域で話されるゲール語の方言や伝統的な歌のスタイルが異な るように、ピーブロックの演奏にも異なる演奏の伝統があり、それぞれのスタイルの正当性を主張する事が 完全に妥当である、という事に起因しているかもしれない。 競争的では無い状況下では、演奏スタイルの違いに対して寛容であることが多く、時には積極的な関心も 持たれ る。このことは、コンペティションの場でも同じことが言える。 スコットランド伝統音楽・歌謡協会が毎年9月に Kinross で開催している伝統歌唱コンペティションは、そういった特別にハッピーな事例である。 この数年前、主催者は、伝統的な歌唱を審査する基準を持つことは不可能であることを認め、2つの単純 だ が効果的な方法を採用した。 一つは、毎年、前年度のコンクールの優勝者を2人の審査員のうちの1人に任命することである(スコッ トランドの伝統的な歌い手こそが、スコットランドの伝統的な歌唱が何であるかを判断する最高の判断者で あるという前提に立っている)。 もう一つは、審査員に、理由はどうあれ、自分が最も気に入ったパフォーマンスをした歌手を「優勝 者」として選んでもらうだけで、次点の歌手については言及しない様にする、というものだ。 こうすることで、この団体の主要な目的である、スコットランドの伝統音楽の演奏を奨励し、そのための 場を提供するということが、競争心に支配されることなく達成されたのだ。 |

|

PROBLEM OF REGIONAL

DIFFERENCES

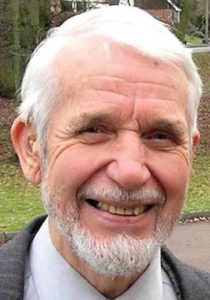

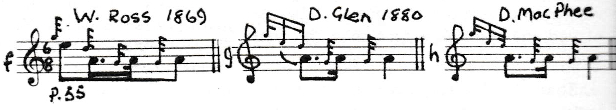

Now the pibroch devotee may well argue that the history of his repertory, unlike that of the Scots song repertory, is marked by rigorous courses of instruction at 'schools' of piping where apprentice pipers memorize and learn to perform a relatively stable repertory in the manner prescribed by his 'guru', and that there is a well-defined aesthetic which should be used as a basis for judging at competitions. This may be true but he would need to consider the problem of regional differences in style which certainly seem to have existed in the late 18th century, and be aware of what can happen if and when one style becomes the favourite of competition judges over a period of years for whatever reason. Let us take as an example the playing of one important formulaic phrase that occurs in many pibroch grounds, the so- called 'echoing beats' on the note A preceded by the G-E-D 'cadence'. Joseph MacDonald was the first piping scholar to notate the echoing beats in his Complete Theory (1762) where he calls them Na Crahinin (shakes or beats); and he quotes from a number of pibroch grounds that contain this formula (e.g. the Lament for the Castle of Dunyveg, Lament for Donald of Laggan, The Groat, and The Earl of Ross's March). In Joseph's time the playing of the E cadence seems to have been quite optional and it is clear that Joseph, who called the 'Introductions', intended the beats on A to be played as he wrote them, with the first A accented and of longer duration than the second (Ex. 1a). |

地域差の問題

さて、ピーブロックの信奉者は、ピーブロックのレパートリーの歴史は、スコッツソングのレパートリー とは異なり、見習いパイパーが「導師」によって定められた方法で比較的安定したレパートリーを記憶し演 奏することを学ぶ、パイピングの「スクール」での厳しい指導課程によって特徴づけられており、競技会で の審査の基準として用いられるべき明確な美学があると主張するかも知れない。 これは正しいかもしれないが、18世紀後半には確かに存在したと思われるスタイルの地域差の問題を考 慮する必要があるだろう。そして、何らかの理由で長年にわたってあるスタイルがコンペティションの審査 員のお 気に入りになった場合、何が起こりうるかを、知っておく必要がある。 例えば、多くのピーブロックのグラウンドに見られる重要な定型句、G-E-Dの「カデンツ」に先立つ A の音でのいわゆる「エコー・ビート」の演奏を例にとってみよう。 Joseph MacDonald は、Complete Theory(1762年)の中で、このエコービートを Na Crahinin(shakes または beats)と呼び、この定型句を含む多くのピーブロックのグラウンド(例えば、the Lament for the Castle of Dunyveg, Lament for Donald of Laggan, The Groat, and The Earl of Ross's March)から引用して、初めて表記したパイピング学者だった。 Joseph の時代には、E-カデンツの演奏はかなり任意だったようで、Joseph は「イントロダクション」と称して、A のビートを彼が書いた通りに、最初の A にアクセントをつけて、2番目よりも長く演奏することを意図したことは明らかである(Ex.1a)。 |

|

|

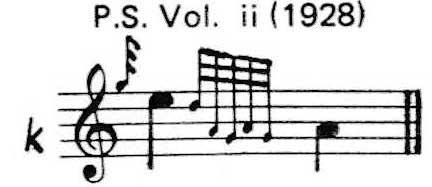

| The earliest staff notated

collection of pibrochs, Angus MacArthur's MS

(1799), also shows the A beats in this way, but

complete with all graces and cuttings, including

the G-E-D cadences (ex. 1b). Donald

MacDonald in his book (1822) and Peter Reid in

his manuscript (1826) also adopted the same

method of writing these beats. Clearly this

seems to have been the way MacArthur-schooled

pipers played them. |

ピブロックの最も古い楽譜集である Angus MacArthur' MS(1799 年)もこのように Aビートを示している。しかし、G-E-D のカデンツを含むすべての装飾音とカッティングを全て含んで完結している(ex.1b)。 Donald MacDonald Book(楽譜集/1822) と Peter Reid manuscript(手書き写本/1826) も、同じ方法でこれらのビートを書いている。明らかに、これは MacArthur スクールで教育を受けたパイパーが演奏する方法であったと思われる。 |

|

|

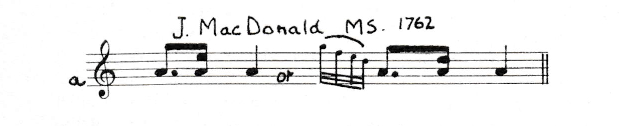

| One also finds evidence of the

same style preserved in the fiddle set of The

Fingerlock published in Patrick

MacDonald's Collection of Highland Vocal

Airs (1784, p. 42). Angus MacKay's record is the first evidence from a piper of a different way of performing these beats — that is with the first two A's being shorter than the third.(Ex.1c). One might argue that the particular way he writes them follows from his decision to write out the E's in the G-E-D cadences as if they were melody notes that take time from the real melody notes (the A's) that follow. |

また、Patrick

MacDonald の Collection of Highland

Vocal Airs (1784, p. 42)に掲載された The

Fingerlock

のフィドルセットにも同じスタイルの証拠が残されていることが分かる。 Angus MacKay が記録したのは、これらのビートを異なる方法、つまり、最初の2つの A を3番目の A よりも短く演奏した最初の例である。(EX.1c)。 このような特殊な書き方は、G-E-D のカデンツの E を、それに続く本当のメロディ音(A)から、時間を置いたメロディ音であるかのように書き出したことに起因している、という意見もあるかもしれない。 |

|

|

|

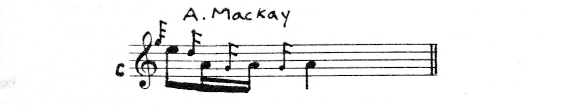

CLASSICAL BAROQUE

The appoggiatura in the classical European baroque style behaves the same way. That this is not the case is shown first by his careful noting of the D and the low G's which are also given a longer time value than the high G and secondly from another source altogether. His father’s good friend Elizabeth Jane Ross (later Baroness D'Oyley, the niece of John MacKay's patron, James MacLeod of Raasay) wrote out several pibrochs in a Manuscript she compiled (c. 1811); presumably it is a record of the way she played them on the pianoforte at Raasay (see A. MacKay's note to Lady Doyle's Salute in his Collection). Wherever this particular formula is called for she writes it as in Ex.1d, with the E in an unaccented position, the D taking the accent and with the obviously pianistic device of sounding quavers B and G (presumably against left hand A Pedal-drone). |

古典派バロック

古典派ユーロピアン・バロックの appoggiatura (という装 飾音)も同じような動きをする。そうでないことは、まず、D と low-G が high-G よりも長い時間値が与えられていることに注意深く注目する事、更に、全く別の資料から示されている。 彼(Angus MacKay)の父の親友 Elizabeth Jane Ross(後の Baroness D'Oyley、John MacKay の後援者である Raasay の James MacLeod の姪)は、彼女が編集したマニュスクリプト(1811頃)にいくつかのピーブロックを書き出しており、 それは恐らく彼女が Raasay の館のピアノでそれらを演奏した記録である(A. MacKay の Collection の Lady Doyle's Salute に対するノートを参照)とされている。 この特定の定型句がどう呼ばれるにせよ、彼女は Ex.1dで示したように E を無アクセントの位置に、D をアクセントにして、B と G の8分音符を鳴らすという明らかにピアニストらしい工夫をして書いている(おそらく左手のAペダルドローンを対象にしている)。 |

|

|

| Whatever one may make of a

pianist's solution to the problem of writing the

formula it clearly suggests that John MacKay

gave some accept to the D as Well as the E in

the cadence and that he played the third A

longer than the first two. That the MacKay way is not just a style of its own and that other pipers gave length to the E in the G-E-D cadence is suggested by some confusion between the cadence E and E's that are part of the melody itself in some settings of 'pibrochs' published by Daniel Dow (in his Collection of Ancient Scots Music for the Violin, Harpsichord or German Flute). Donald MacDonald appears to have been aware of other ways of playing the A beats, for his manuscript collection (presumably compiled after his book, when he must have been exploring the repertory outwith his own tradition) contains different ways of writing the formula (Ex.1e.). Angus MacKay was also aware of the MacArthur/MacDonald style, for at some time, when he had possession of the MacArthur manuscript, he marked in the index those pibrochs which differ "from my father's style of playing", but passes no judgement on the style. |

ピアニストが定型句を書くという問題をどう考えるかはともかく、John MacKay

がカデンツの E だけでなく D にも何らかの配慮をし、3番目の A

を最初の2つよりも長く演奏したことは明らかである。 MacKay 流が独自のスタイルで はなく、他のパイパーもG-E-D のカデンツの E に長さを与えていたことは、Daniel Dow により出版された楽譜集(Collection of Ancient Scots Music for the Violin, Harpsichord or German Flute) のピーブロックのいくつかの セッティングに於いて、カデンツの E とメロディの一部である E が混乱していたことからもうかがい知ることができる。 Donald MacDonald は Aビートの別の演奏法も知っていたようで、彼のマニュスクリプト(おそらく彼の出版された楽譜集の後に 編集され、彼は自分の伝統にとらわれずにレパート リーを探求していたはず)には様々な式の書き方が含まれている(EX.1e.)。 Angus MacKay も MacArthur/MacDonald のスタイルを認識していたようで、MacArthur MS を所有していたある時期、インデックスに「父の演奏スタイルと異なる」ピーブロックに印を付けているが、スタイルについての判断はして いない。 |

|

|

|

QUESTION OF STYLE

None of the canntaireachd collections of the time give us much help in deciding which was the more common style. Gesto (1828) usually writes (Hieririn for this formula and John MacKay in his Specimens of Canntaireachd also quotes hianana and occasionally hiaanana. The a in the hiharin of Colin Campbell's collection may conceivably be A reference to the prominent sound of the D in the MacKay style. A generation later William Ross (1869) is seen to be advocating the playing of all tunes in MacKay's manner, for in his instructions he states "All the run down Grace notes in MacDonald's piobaireachds ought to be played with a rest on the E grace note". He usually adopts MacKay's style for the complete formula (except for the extra length of the D and G grace notes), but in two pibrochs. The Lament for the Only Son and Queen Anne's Lament, he dots the first A and shortens the second as if admitting that the MacKay style simply isn't right for certain tunes (Ex. 1f). |

スタイルの問題

当時のカンタラック集には、どちらがより一般的なスタイルであったかを決定する上で、あまり参考にな るものはない。 Gesto(1828)は通常この式を Hieririn と書き、John MacKay も 彼の Specimens of Canntaireachd の中で hianana と、時々 hiaanana と書いている。 Colin Campbell のコレクションにある hiharin の A は、MacKay スタイルで顕著な D の音に掛かったものだと考えられる。 後の世代の William Ross(1869) は「MacDonald の楽譜集 における全ての run down 装飾音は、E 装飾音に休符をつけて演奏すべきである。」として、全ての曲を MacKay の方法で演奏することを推奨していると思われる。 彼は通常、2つのピーブロクを除いて全曲に MacKay のスタイル(D 音と G 音の余分な長さを除く)を採用している。しかし、2つの曲、The Lament for the Only Son と Queen Anne's Lament に於いては、まるで MacKay 式が特定の曲に適していないことを認めるかのように、最初のAに点を入れ、2番を短くしている(Ex.1f)。 |

|

|

| The two other collections of the

second half of the nineteenth century appear to

restate the MacDonald/MacArthur style as far as

the beats on A are concerned. Donald MacPhee (1880) writes them as in Ex.1h. and David Glen (1880-99) as in Ex.1g. But both attempt to indicate differing degrees of note length in the G-E-D cadence which perhaps represents a modification of the MacDonald style in favour of that of MacKay. David Glen in a footnote to the pibroch The Blue Ribbon, which appears in his Highland Bagpipe Tutor (1881), tries to show how one should play the E cadence along with the A formula, but he does not help matters by quoting standard academic musical theory as if it applied equally to Gaelic music: — |

19世紀後半の他の2つの楽譜集では、A のビートに関する限り、

MacDonald/MacArthur スタイルに回帰しているようだ。 Donald MacPhee(1880) は EX.1h の様に、David Glen(1880-99)は EX.1g の様に書いている。 しかし、両者とも G-E-D のカデンツにおいて異なる音符の長さを示そうとしており、これはおそらく MacDonald スタイルを MacKay スタイルに修正したものである。 David Glen は、彼の Highland Bagpipe Tutor (1881)に掲載されている The Blue Ribbon の脚注で、A の形式と一緒に E カデンツをどう演奏すべきかを示そうとしているが、標準的な学術的音楽理論を引用して、それがゲール音楽にも等しく適用されるかのように言って、問題を解 決していない:ー。 |

| "In this class of

music.........there are two kinds of grace

notes, the first a short one, the Acciaccatura

— is the one the pupil has already become

familiar with in Marches etc. And its

purpose is the same, namely to accentuate and

divide the notes of the melody. The second kind, a long one, — the Appoggiatura — also a small note, may be said to form part of the melody. This grace note should indicate how much is to be taken from the principal or melody note which follows it; but this is not always done. When the principal note is even, it as a rule takes one half, when dotted, it takes two thirds or the length of the note, leaving the melody note the length of the dot. These two kinds of grace notes are frequently used in combination, as in the above "Cadence", the first one G is one of the short kind, and it is used to accentuate the first of the next two grace notes which are of the long kind. Some players make the "E" in the above Cadence of such a length that no musical sign will serve to indicate its duration. When it has to be made specially long a "Pause” is sometimes written over it, but its performance is usually left very much to the pleasure of the performer." (p.29) |

「これらの楽曲では......2種類の装飾音がある。1つ目

の短い装飾音 "the Acciaccatura"

は、生徒がすでにマーチなどで慣れ親しんでいるものである。

その目的は同じで、メロディーの音を加速させ、分割することである。 2つ目の長い装飾音 "Appoggiatura" も小さな音で、メロディの一部を形成していると言えるかもしれない。この装飾音は、それに続く主音または旋律音からどれくらい取るかを指示する必要 があるが、これは常に行われているわけではない。 主音符が偶数である場合は2分の1、付点音符の場合は3分の2または音符の長さを取り、メロディー音 符は付点の長さを残すのが一般的である。 この2種類の音符はよく組み合わせて使われる。上の『カデンツ』のように、最初の G は短い音符で、次の2つの長い音符の最初のアクセントに使われる。 奏者によっては、上記のカデンツの "E" を、楽譜で示している事がまるで意味を為さないかの様な長さにすることがある。特別に長くしなければならないときは、その上に『ポーズ』が書かれることも ありるが、その演奏は通 常、演奏者の好みに大きく委ねられている。」(p.29) |

|

TWO PLAYING STYLES

The reader may well be wondering about the need for all this detailed and tedious documentation. Its purpose has been to determine that, in the late 18th and through the 19th century, at least two different playing styles existed and to try and trace their development over the next 100 years. We have noted a tendency for the two styles to merge as far as the playing of the E cadance is concerned, but not in the case of the echoing beats on A. The way the beats are played strongly affects the character of many pibroch grounds and the way the cadence E's are played undoubtedly affects the structure and rhythmic flow of pibroch grounds when ever they appear,as they affect many variations too. A study of both should provide a useful index to changes in performance style. Unfortunately there is little or no evidence in the 19th century as to what people thought about the two styles, other than that which is inherent in the notations themselves. Competitions in pibroch playing continued with few interruptions throughout the 19th century, but as far as we can gather the judges, even if they knew anything about the music they were judging, had little say as to which pieces were to be played, or how they were to be rendered. All this changed in the early years of the 20th century and in the second part of this article we shall look at the effects of this change on the tradition and in particular its effect on the MacArthur/ MacDonald style. |

2つの演奏スタイル

読者は、このような詳細で退屈な解説の必要性について疑問を感じるかもしない。 これまでの解説の趣旨は、18世紀後半から19世紀にかけて、少なくとも2つの異なる演奏スタイルが 存在したことを明らかにし、その後100年にわたるその発展をトレースすることである。 E カダンツの演奏に関しては、この2つのスタイルが融合する傾向にあるが、A のエコービートに関してはそうではない。 エコービートの演奏方法は多くのピーブロックのグラウンドのキャラクターに強く影響する。そして、カ ダンツ E の演奏方法は、ピーブロックのグラウンドの構造とリズムの流れに間違いなく影響すると共に、バリエーションにも多大な影響を及ぼす。 この2つを研究することで、演奏スタイルの変化に対する有効な指標となるはずである。残念ながら、 19世紀の人々がこの2つのスタイルについてどのように考えていたのか、楽譜に書かれていること以外に はほとんど証拠がない。 ピーブロック・コンペティションは19世紀の間、ほとんど中断することなく続けられたが、私たちの知 る限り、審査員は、たとえ審査する音楽について何か知っていたとしても、どの曲を演奏すべきか、どのよ うに演奏すべきかということについては、ほとんど発言することがなかった。 しかし、このような状況は20世紀初頭に変わった。この記事の後半では、この変化が伝統に及ぼした影 響、特に MacArthur/ MacDonald スタイルに及ぼした影響について見ていきたいと思う。 |

|

Part2

|

|

|

|

| In the first part of

this article I described how two distinct

performing traditions, which existed at the end

of the 18th century, could be exemplified in the

way notators chose to write out what is best

regarded as one formulaic motif — the echoing

beat on A introduced by the "E cadence". I chose this formula because the way it is played can radically affect how one perceives the melody of a Ground as a whole. While surveying 19th century collections I suggested that by the 1880's, when Donald MacPhee's Collection and the first part of the David Glen Collection appeared, the two styles — that of the MacArthurs and MacDonalds on the one band and that of Angus MacKay on the other — were becoming confused by some Pipers. General Thomason's monumental but compact Ceol Mor appeared in 1900, in which he unsuccessfully attempted to sort out some of the confusion. The MacPhee and Glen notations suggest that by the 1880's virtually all pipers gave length to the E in the cadence, but that not all of them also gave any length to the D — many apparently preferred to treat it as an ordinary grace note. But how the first A was played then we are not sure. Neither was Thomason. Writing about the formula he commented : "E is a prominent note in all these beats. . . The relative values of E and the primary note ... [as he notates them] . . . are more or less conventional”. He added that in any case the proper timing of the formula "is not likely to be acquired correctly whatever the notation may be - without the aid of a master” (Ceol Mor Notation, 1893, p.9). |

本稿の前半では、18世紀末に存在した2つ

の異なる演奏の伝統の違いは、それぞれの楽譜の記譜者が「Eカデンツから入る A

のエコービート」という一つの定型モチーフと見なすものを、それぞれのどのように表記するか?という事に表れていることを説明した。

私がこの定型モチーフを選んだのは、その演奏方法によって、グラウンドの旋律全体の捉え方が大きく変 わるからだ。 19世紀のコレクションを調査していると、1880年代、Donald MacPhee の Collection と David Glen の Collection の最初の部分が登場する頃には、2つのスタイル(MacArthurs と MacDonalds のスタイルと Angus MacKay のスタイル)が、一部のパイパーによって混乱し始めていることが示唆された。 1900年には Thomason 少将の記念碑的かつコンパクトな Ceol Mor が出版された。彼はその中で混 乱の一部を整理しようと試みたが、失敗に終わっている。 MacPhee と Glen の表記によると、1880年代には事実上すべてのパイパーがカデンツの E に長さを与えていたが、すべてのパイパーが D に長さを与えていたわけではなく、多くの場合、通常の装飾音として扱うことを好んでいたようだ。 しかし、最初の A がどのように演奏されたのかについては、私たちにはよく判らない。Thomason でも同じだ。 彼はこの定型についてこうコメントしている。「Eはこれらのすべてのビートで目立つ音で ある。E と主音との相対的な値は(彼が記したように)多かれ少なかれ伝統的なものである。」と述べている。 彼は、いずれにせよ、この定型の適切なタイミングは「どんな表記法であろうと、師匠の指導が無くて は、正しく習得することはできないだろう。」(Ceol Mor Notation, 1893, p.9)と付け加えている。 |

|

|

|

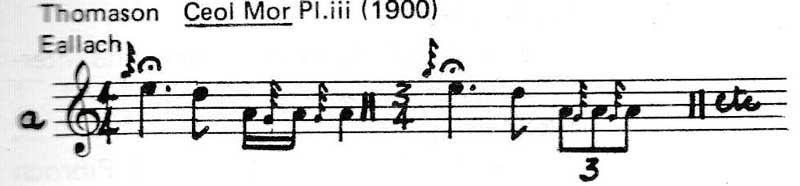

THOMASON'S VIEWS

For Thomason there were actually two basic ways of rendering the formula and he labelled them the 'Gairm' (or 'Call') and the 'Eallach' (or 'Burden'). He notated the 'Eallach' showing length for the note D as well as E, and, according to the musical metre, he shows five diff erent ways of writing the 'Eallach' (see example 2a). Example 2b shows how he generally treated the 'Gairm'. |

Thomason の見解

Thomason は、定型の表記方法として、'Gairm'(or 'Call')と 'Eallach'(or ’Burden')という2つの基本的な方法を提示している。 'Eallach' は E と同様に D の長さを表記し、音律に従って5種類の 'Eallach' の書き方が示されている(ex. 2a 参照)。Ex. 2b は、彼が一般的に 'Gairm' をどのように扱っていたかを示している。 |

|

|

| However, five years after Ceol

Mor appeared, this indefatigable

researcher had changed his mind (in his revision

to Ceol Mor, Abbreviated Notation,

1905), and he set out to correct, among other

things, what he admitted was "a serious defect

in the first edition of Ceol Mor", a

failure to distinguish between "full" double

echoes (eallach) and "broken" double

echoes (gairm). The broken form which he then introduced is none other than the formula as played in the MacArthur/ MacDonald style with a long first A (ex.2c) |

しかし、Ceol Mor が出版されてから5年後、

この不屈の研究者は考えを改め (Ceol Mor,

Abbreviated Notation,

1905の改訂版)、特に「完全な」ダブルエコー(eallach)と「壊れた」ダブル

エコー(gairm)を区別していない事は「Ceol Mor

の初版における重大な欠陥」だと認め、訂正に乗り出した。 そして、彼が提示した壊れた形式は MacArthur/MacDonald スタイルで長い最初の A で演奏される形式(ex.2c)に他ならず、 |

|

|

| while the 'full' eallach

represents the formula played with a short or

equal first A (ex. 2d). |

「完全」 eallach は短いまたは等しい長さの最初の A

で演奏される式(ex.2d)で ある。 |

|

|

| He makes an interesting

statement in his revision: - "Pipers of the

present day will not, as a rule, admit of the

distinction between the Eallach and the Gairm,

but the Author cannot concede this

point. It used to be very marked in

his early piping days and is still to be traced

in Skye. How the distinction has vanished now,

it is impossible to say, but it is a great pity

. . . " Thomason's "early piping days” date back to the 1850's when he himself was a beginner on the pipes and when he first noted the formulaic nature of many pibroch grounds (see page v of his introduction to Ceol Mor). Thomason suggests (probably mistakenly) that these two different ways of playing the formula could actually occur in the same piece. |

彼はその改訂版で次のような興味深い記述をしている:-「現在のパイ

パーは、原則として、 Eallach と Gairm

の区別を認めないが、著者はこの点を譲ることはできない。初期のパイピング時代には、この区別は非常に顕著であり、今でもスカイ島ではその痕跡を見ること

ができる。現在では、その区別がどうやって消滅してしまったかは分からないが、非常に残念なことであ

る…」。 Thomason がここで言っている「初期のパイピング時代」とは、彼自身がパイプの初心者だった1850年代にさかのぼり、彼は多くのピーブロックのグラウンドの定型的 な性質に初めて気付いていた(Ceol Mor 序文5頁を参照)。 Thomason は、この2つの異なる演奏方法が、実は同じ曲の中で起こり得ることを(おそらく間違って)示唆してい る。 |

|

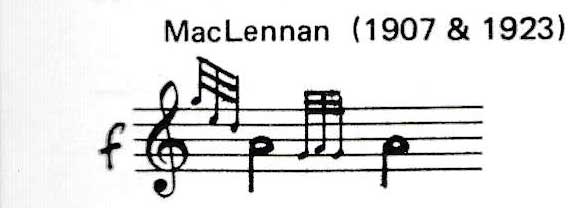

NOT A CLEAR CASE

If for him in 1905 it was not a clear case of two different styles, for others it is, and feelings about the two styles are polarising. At least one authority still has an open mind however. David Glen's collection The Music of the Clan MacLean (1905) contains an interesting footnote to a setting of The Bicker, here called MacLean of Coll Putting his Foot on the Neck of His Enemy, which Glen collected from Coll's piper, John Johnson. Presumably Johnson learned his art from the Rankins - hereditary pipers to the MacLeans - before the last of them emigrated to Prince Edward's Island early in the nineteenth century. Johnson's curious way of playing E cadences intrigued Glen so much that he notated the style, a style where there is no pause on E or D but where the piper briskly tumbles down to the melody note (ex. 2e). Since some of the later Rankins were trained in Skye, could this way of playing have been typical of that of the MacArthurs and MacDonalds? In other words, did they play them as they actually wrote them? Glen's footnote is tantalising for his example stops just short of the bar where the A formula is used. But there are still pipers around who are in no doubt that the A should be played long. In 1907 Lt. John MacLennan, for example, complained that the practice of playing echoing beats on A as a birl was now common (presumably the birl results from pipers rattling through MacKay's version) and to counteract this MacLennan adopted a notation that exaggerated the length of the first A (ex. 2f). |

明確な事例ではない

1905年当時、彼にとって2つのスタイルが明確でなかったとしても、他の人にとってはそうであり、 2つのスタイルに対する思いは両極端であった。しかし、少なくとも一人の権威者は、まだ柔らかい頭をし ていた。 David Glen の The Music of the Clan MacLean (1905)に は、Glen が Coll のパイパー John Johnson から収集したThe Bicker(ここではMacLean of Coll Putting his Foot on the Neck of His Enemy) のセッティングについて興味深い脚注が掲載されている。 おそらく Johnson は、MacLean 家の世襲パイパーであった Rankin 家の最後の一人が、19世紀初頭にプリンス・エドワード島に移住する前に、彼から演奏技術を学んだと考 えられる。 Johnson の Eカデンツの不思議な奏法に興味を持った Glen は、E や D で間を置かず、メロディー音まで素早く転がり込むスタイル(ex. 2e) を記譜した。 後期の Rankin 一族の中にはスカイ島で修行した者もいるので、この演奏方法は MacArthur 一族や MacDonald 一族の典型的な演奏方法だったのだろうか? 言い換えてみれば、彼らは実際に書いた通りに演奏したのだろうか? Glen の脚注は、彼の例が A 定型が使われる小節のすぐそばで止まっていることから、興味をそそられる。 しかし、A を長く弾くべきと信じて疑わないパイパーが他にもまだいる。 例えば1907年、John MacLennan 中尉は、A のエコービートを birl として演奏する習慣が一般的になっていると苦言を呈し(恐らく birl は、パイパーが MacKay のバージョンに取り組む事で生じる)、これに対抗す るために、最初の A の長さを誇張する形で表記した(ex. 2f)。 |

|

|

| He also felt that the habit of

leaving the length of the E in the cadence to

the pleasure of the performer had resulted in

the destruction of the rhythm of the ground, for

pipers were making the E too long (see his

preface to Piobaireachd as the MacCrimmons

Played It). In his second volume, published post humously 16 years later, he reiterated his complaint about the birl, comparing the modern way of playing the formula to the "neighing of the horse" (The Piobaireachd as Performed in the Highlands for Ages, Till About the Year 1808). But we have now reached the time of the founding of the Piobaireachd Society, whose work so far as this formula is concerned was to prove crucial in determining the fate of the different styles, because of its early policy that pipers must play in competitions 'according to the book' (i.e. follow whatever is the approved setting). The Society was founded in 1903 and its first four books (1905, 1906, 1907 and 1910) show how successive committees plumped for one or the other of the two styles of writing out the double echo. Dr. Charles Bannatyne's influence is seen in the two middle books where the MacDonald/MacArthur style is adopted (Ex. 2g) |

彼はまた、カデンツの E

の長さを演奏者の好みに任せる習慣が、パイパーが E

を長くしすぎて、グラウンドのリズムを破壊する結果になっていると感じていた(Piobaireachd

as the MacCrimmons Played It の序文を参照のこと)。

16年後に出版された第2巻では、彼は birl についての不満を繰り返し、この定形に於ける現代の演奏方法を「馬のいななき」に例えている(The Piobaireachd as Performed in the Highlands for Ages, Till about the Year 1808)。 しかし、私たちは今や、ピーブロック・ソサエティー設立の時を迎えた。ピーブロック・ソサエティー は、コンペティションの場でのパイパーは、この定型に関する限り「楽譜集に沿って(つまり、承認された セッティングには必ず従って)」演奏しなければならない、という初期の方針を示した事から、異なるスタ イルの運命を決定する上で重要な役割を果たすことになった。 ソサエティーは1903年に設立され、最初の4冊の楽譜集(1905年、1906年、1907年、 1910年)は、歴代の委員会が、ダブルエコーを表記する際に、如何に2つのスタイルのうちどちらか一 方を採用していたかを示している。 Dr. Charles Bannatyne の影響は、MacDonald/MacArthur スタイルを採用した中間の2冊に見られ(Ex. 2g)、 |

|

|

| and, in the Oban Times, both he and Lt. John MacLennan strongly attacked the fourth book where the committee had reverted to a modified form of MacKay's version (Ex. 2h), said to have been produced with the aid of such pipers as John MacDonald of Inverness, J. MacDougall Gillies and W. Ross (Scots Guards) (see Preface Book 4, 1910). | Oban Times の中で、彼と John MacLennan 中尉は、John MacDonald of Inverness、J. MacDougall Gillies、W. Ross(Scots Guards)などのパイパー等の助言に従って策定されたと言われている、MacKay バージョン(Ex. 2h)に改変した4冊目を強く攻撃している。(1910年の Book 4 の序章を参照)。 |

|

|

|

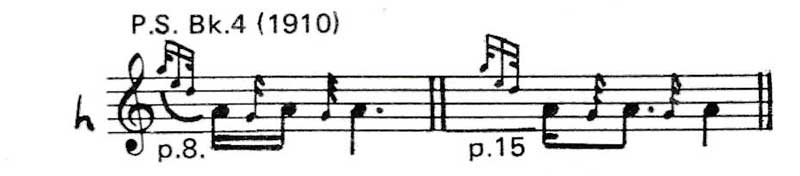

QUESTION SETTLED

The first volume of the new series edited by Maj. J.P. Grant of Rothiemurchus eventually settled the question of what was in future to be the approved way of playing our formula. MacKay's style is preferred to MacDonald's from the very outset, but the formula is notated showing a birl on a minim A (Ex. 2j) or in later volumes with a crotchet E (taking the accent) followed by the birl (Ex. 2k). |

問題の決着

J.P. Grant of Rothiemurchus 陸軍少佐が編集した(1925〜の)新シリーズの第1巻で、今後この形式をどのように演奏することが許されるのか、という問題が最終的に提示された。 当初から MacDonald よりも MacKay のスタイルが好まれていたが、この形式には2分音符の A に birl をつけて表記され(Ex. 2j)、後の巻では4分音符の E(アクセントを取る)の後に birl をつけて表記された(Ex. 2k)。 |

|

|

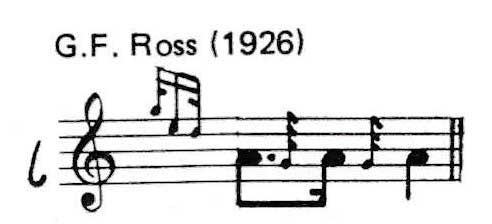

| The music committee justified

their notation because of the "unanimity which

exists among the players, who have inherited the

traditional teaching, as to the correct way of

fingering these movements in spite of recorded

staff notation." (Preface Vol. i, p.iv). That there could not have been unanimity made little difference. With pibroch playing receiving recognition only on the competition platform, these words and the new settings dealt what was perhaps the final blow to the MacArthur/MacDonald way of playing the formula and it is interesting that any later public protests about how it should be played came mostly from outside Scotland, away, that is, from competitions supervised by the Society. The most articulate commentator was G.F. Ross writing from Calcutta in two books (published by Henderson of Glasgow) in 1926 and 1929 : they were presumably by way of reply to the Piobaireachd Society's first book in the new series. In the preface to his first volume Ross stated : "The principal source of argument is the playing of the double beat on low A" (p.16) and he expands on this theme in his second volume in his 'Word to the player':— "What causes, above all, loss of rhythm in these days is the over dwelling on the E of the G-E-D cadence and the rushing of the double beat on A . . The double beat on A should be played as written herein [Ex. 2I] |

音楽委員会がこの表記を正当化したのは「(古い楽譜集等の)五 線譜には(他の形式が)記録されてはいるが、これらの

運指の正しい指遣いは、伝統的な教えを受け継いでいる演奏家の間で一致しているためである。」(序章第

一巻四頁)とある。 しかし、そのような意見が一致するはずもない。 ピブロックの演奏はコンペティションの場でしか認められていなかったので、この言葉と新しいセッティ ングは、MacArthur/MacDonald の演奏方式におそらく最終的な打撃 を与えた。 この後、ピーブロックの演奏方法をこの様に演奏すべきという事に対して、公に抗議があったのは、殆どがスコットランド国外から、つまりソサエティーが監督 するコンペティションから離れた場所からだった、というのは興味深いことである。 最も明確な論者は G. F. Ross で、1926年と1929年にカルカッタから2冊の本(グラスゴーの Henderson から出版)をリリースしている:これらは恐らくピーブロック・ソサエティーの新しいシリーズの最初の本への応答として書かれたものと思われる。 第1巻の序文で Ross は次のように述べている。「論争の主な原因は、Low A のダブルビートの演奏についてである」(p.16)。そして、第2巻の「奏者への言葉」で、このテーマを拡大している:「最近のリズムの喪失の原因は、何 よりも、G-E-D のカデンスの E にこだわりすぎることと、A のダブルビートを急ぎすぎることである。A のダブルビートとはここに書かれているように弾くべきで[Ex.2I]、 |

|

|

| and should not on any account be rushed as some modern publications would indicate. . . . Therefore, when seeking for the rhythmic swing of a tune, find the rhythm of the double beat on A by the omission of the cadence. ... It should be observed that where the double beat on A is followed by a long A to complete the bar the rhythm of a tune will generally demand the longest accent on the first A of the double beat, rather than on the last. This view is confirmed by Joseph MacDonald in his Treatise on the 'Scots Highland Bagpipe' ". | 現代の出版物にあるような急ぐようなことは一切してはいけない。. . . したがって、曲のリズムの揺れを求めるときは、カデンスの省略によって A上のダブルビートのリズムを見つけること。... A のダブルビートに長い A が続いて小節が完成する場合、曲のリズムは一般的にダブルビートの最後の A ではなく、最初の A に長いアクセントを置くことが求められるべきだ。この見解は、Joseph MacDonald の "Treatise on the Scots Highland Bagpipe" でも確認されている。」 |

|

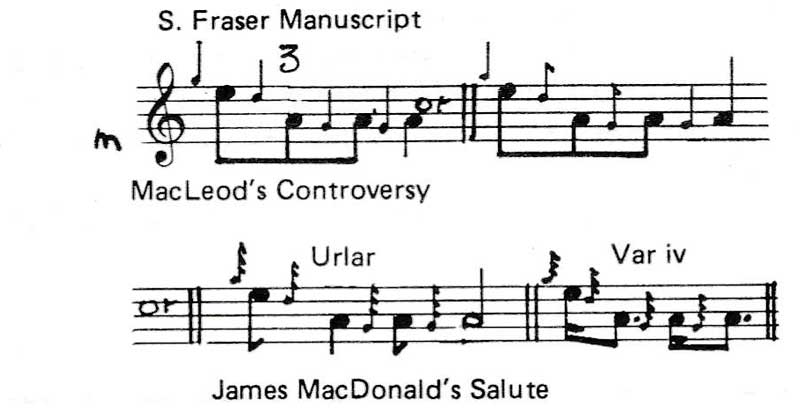

AUSTRALIAN PIPER

Ross had, by 1926, to look back to the distant past for confirmation of his strongly held views; but he looked also to Simon Fraser, an Australian piper who had been corresponding at great length over several decades with pipers all around the world about the style he had learned. Simon Fraser was a pupil of Peter Bruce of Glenelg, a prize-winning piper in the Highland Society of London's competition in 1838. Peter Bruce had emigrated to Australia taking with him what he had learned from his father Alex, who was reputed to be Donald Ruadh MacCrimmon's favourite pupil. I have not been able to inspect the complete Simon Fraser manuscript collection (in the possession of Dr. Barrie Orme of Melbourne) but was able to note two of Fraser's ways of writing the formula we are discussing (Ex. 2m). |

オーストラリア人パイパー

Ross は1926年まで、自分の強い信念を確認するために遠い過去に目を向けていた。しかし、彼は同時 に、オーストラリア在住のパイパー、Simon Fraser にも目を向けた。Fraser は数十年に渡って世界中のパイパーと、自分が学んだスタイルについて長い間やり取りをしていた Simon Fraser は、The Highland Society of London が1839年に開催したコンペティションで優勝した Peter Bruce of Glenelg の弟子であった。Peter Bruce は Donald Ruadh MacCrimmon の愛弟子と言われた、父親の Alex Bruce から学んだ演奏技術を携えてオーストラリアに移 住してきた。 私は Simon Fraser のマニュスクリプト(メルボルンの Dr. Barrie Orme 所蔵)の全文を見ることはできなかったが、Fraser が今回取り上げる形式をどのように書いたかについて、2つ確認することができた(Ex. 2m)。 |

|

|

| They pose a fascinating question

: could they be evidence of how Donald Ruadh

played echoing beats? If so, where did John MacKay get his style? Simon's son, Hugh, seems to have abandoned his father's style of playing echoing beats on A: we know this from a recording made by Hugh when in his 80's and kindly supplied to the School of Scottish Studies by Dr. Orme. So as a playing tradition this detail of Fraser's style has apparently died out in Australia. The writer has discovered only one piper in Scotland who insists on playing and notating echoing beats with a long first A: this is George Moss of Kessock who tells me that long ago he opted out of the competitive field of piping because he refused to adapt his style to that favoured by judges in competitions. |

これらは、Donald

Ruadh

がどのようにエコービートを演奏していたかを示す証拠となりうるのか、という興味深い問題を提起してい

る。もしそうだとするなら、John MacKay

はどこで彼のス タイルを手 に入れたのだろうか? Simon の息子の Hugh は、A のエコービートについて、父のスタイルを放棄したようだ。これは、Hugh が80才代の時に録音し、Dr. Orme の好意で School of Scottish Studies に提供されたものである。このように、オーストラリアでの演奏の伝統の中で、明らかに Fraser スタイルは途絶えてしまったようだ。 筆者はスコットランドでただ一人、長い最初の A でエコービートを演奏し、記譜するパイパーを発見した。それは George Moss of Kessock で、彼は遥か昔に自分のスタイルをコンペティションの審査員が好むスタイルに合わせる事を拒んで、コン ペティション・フィールドから敢えて飛び出したと話 した。 |

|

|

| There is also the evidence of a

Uist piper, Calum Beaton, who told me once that

an uncle of his used to play with a long first A

until John MacDonald of Inverness came out to

teach in South Uist as the Piobaireachd

Society's instructor and told him this was

'wrong'. I must admit to being impressed by the musical sense to be heard in this apparently obsolete pibroch style and this brings us back to the reason for this long and perhaps tedious piece of documentation. It is to pose the following question. |

また、Uist のパイパー、Calum Beaton は、John MacDonald of Inverness

がピーブロック・ソサエティーの指導者として South Uist

に教えに来た際、これは「間違いだ」と言うまで、彼の叔父は最初の A

を長く演奏していた、と言っている。 私は、この一見時代遅れのピーブロックスタイルから聞こえる音楽的センスに感動したことを認めざるを 得ない。そして、そして、それは我々が何故この長くて退屈な資料を作成している理由に立ち戻らせる。そ れは、次のような問いを投げかけるためである。 |

|

CASE FOR RE-ASSESSMENT?

If we accept that pipers are today playing a repertory, which in its heyday more than 200 years ago was performed in a number of different styles, depending on how far the main centres of performing and teaching were isolated or otherwise from each other; and if we accept that performance styles have inevitably changed through time, some merging with others, some even dying, is there not a case for a reassessment of today's tradition, or at least for an honest attempt at reconstructing some of these earlier styles? Such an approach is not uncommon in other musical fields. There is for instance the work of the late David Munrow whose research and performance of European medieval and renaissance music was a catalyst to a tremendous flowering of interest in 'early music'. Some of his efforts at historical reconstruction initially outraged some of the more academic historians, but his sheer musicianship allied with scholarship won him the respect of thousands, among both the general public and his peers. At least one piper, P/M James McColl of California has already begun a reappraisal, with daring experiments with the tempos of pibrochs. Even if those pibroch enthusiasts present at this year's Piobaireachd Society conference had enjoyed hearing recordings of McColl's playing, they know that he would not be considered for a place in competition today. In any case some of his tempos could be faulted in historical and musical grounds. But what if another competent piper offered a rendering of Hector MacLean's Warning just as it is written in the MacArthur MS, complete with long first A's, preceded perhaps with short tumbling G-E-D cadences for good measure? This should be a different matter, for as I have tried to show there is solid documentary evidence to suggest that some pipers traditionally played that way. Until such an experiment is not felt to be out of place in competitions it would be worth creating a non-competitive platform (even at competition meetings) for such experiments. All else that is needed is for pibroch players to be prepared to put behind them what knowledge may have come down to them in a master-pupil succession by admitting the possibility of change during the last two centuries. Then they can look afresh at the historical records created at a time when the MacArthur, MacCrimmon and Rankin pipers were still alive and playing. |

再評価すべき事柄ではないのか?

今日のパイパーたちが、200年以上前の全盛期には、演奏や技術伝承の主な中心地が互いにどの程度離 れていたかによって、多くの異なるスタイルで演奏されていたレパートリーを演奏しているという事実を、 もし私たちが受け入れるならば、そして、それらの演奏スタイルは時代とともに必然的に変化し、一部は他 と融合し、一部は消滅さえした、という事実を私たちが受け入れるならば、今日の伝統を評価し直す事、或 いは、少なくともこの様な昔のスタイルの一部を復元しようとする、誠実な取り組みをすべきではないだろ うか? このようなアプローチは、他の音楽分野でも珍しいことではない。 例えば、故 David Munrow の研究がある。彼のヨーロッパ中世・ルネサンス音楽の研究と演奏は "early music" への関心を大きく開花させるきっかけとなった。 その歴史的再構築の努力の一部は、当初、より学術的な歴史家たちを激怒を買ったが、学問と結びついた 彼の純粋な音楽家魂は、一般の人々や同業者の間で、計り知れないほどの尊敬の念を集めた。 少なくとも一人のパイパー、カリフォルニア在住の P/M James McColl は、ピーブロックのテンポに大胆な実験を行い、すでに再評価を始めている。 今年のピーブロック・ソサエティーのカンファレンスに出席していたピーブロク愛好家たちは、たとえ MacColl の演奏の録音を聴いて楽しんだとしても、今日、彼がコンペティションで入賞することはないだろう、ということを知っている。いずれにせよ、彼のテンポのい くつかは、歴史的、音楽的な理由で非難される可能性がある。 しかし、もし他の有能なパイパーが Hector MacLeanのWarning を MacArthur MSに書かれている通りに演奏し、最初の A を長く演奏し、その前に G-E-D のカデンツを短く転がすとしたらどうだろう? 私が示そうとしたように、伝統的にそのように演奏していたパイパーがいたことを示す、確かな文書上の 証拠があるので、これはまた別の問題である。 このような実験的取り組みが、コンペティションにそぐわないと思われなくなるまでは、そのような実験 のための非コンペティション(もちろん、コンペティションでも)のプラットフォームを作る価値がある。 ピーブロック奏者にとってこの他に必要なことは、この2世紀の間に演奏技術が変化したという可能性が 有るという事を認識した上で、師匠ー弟子の関係の中でどの様な知識が受け継がれてきたか、という事を受 け入れる覚悟が必要である。 そうする事によって、MacArthur、MacCrimmon、Rankin のパイパーたちがまだ生きて演奏していた時代に作られた、歴史的な業績を新たに見直す事が可能になる。 |

お読みになった通り、これは George Moss や Simon Fraser 等が正当性を主張する、いわゆるオールドスタイル、言い換えれば、MacArthur/MacDonald の演奏スタイルの復権、再評価の必要性を理論的に説明している記事だと言えましょう。この記事から遡ること数年前の 1970年代初頭に、彼が《発見》した George Moss の元に足繁く通って、その主張の正しさを確信した Peter Cooke としては、黙っては居られなかったのでは無いでしょうか。

この記事も含めて、あれこれ読み進めてきた中で見えて来たのは、貴族社会の主従関係がダイレクトに反映されていた、当 時のスコットランドのパイピング界に於いては、John MacDonald of Inverness、J. MacDougall Gillies、W. Ross といった主だったプロフェッショナル・パイパーたちは、完全に貴族社会の子飼いパイパー状態であったという事。その様な 子飼いパイパーが飼い主に対して異議申し立てをする事は有り得ません。それどころか、権威筋の連中はパイピング界に轟 く彼らプロフェッショナル・パイパーたちの高い名声を盾にして、自分たちの身勝手で悪質な改変を都合良く正当化してい た、という構図が良く見えて来ました。

その様な中で、当時のピーブロック・ソサエティーの決定に対して、非難の声を発したのは主に海外からであったという事 は十分に肯けます。John A. MacLellan が自ら編集する新しいパイピング雑誌に "International" というタイトルを使ったのは、スコットランド国内の自浄作用だけでは、真に民主的なパイピング界の実現は到底不可能と思われたからではないでしょ うか。

Peter Cooke は、記事の最後で「実験のための非コンペティションのプラットフォームを作る価値がある」と提案しています。正にそれを具現化したとも言える Donald MacDonald Quaich がスタートするのは、この記事からほぼ10年後の1987年6月の事。そして、多様なピーブロックの在り方を取り戻そうとする組織として Alt Pibroch Club が始動する 2013年までには、更に四半世紀、この記事からは35年の年月が必要でした。

Dr. Peter Cooke は 2021年1月に90才で亡くなられました。逝去を報じる記事(Bagpipe News on January 5, 2021)に追って掲載された追悼文 "Dr. Peter Cooke, an appreciation" (Bagpipe News on January 14, 2021)の中で、2015年当時に "Piping Times" 最後の編集長であった Stuart Letford の文章の次の様な記述が印象的です。

Peter gave a few talks to the Piobaireachd Society Conference and wrote some articles that were published in the Piping Times and in The International Piper, two of which can be read here. To me, he was convincing in many respects but not all and I understand that James Campbell (son of Archie Campbell of Kilberry) was dismissive of many of Peter’s points. It is a brave man who would try to discredit Angus MacKay!

[ Peter は Piobaireachd Society Conference で何度か講演をし、Piping Times と The International Piper に掲載されたいくつかの記事を書きました。私にとっては、彼は多くの点で説得力があったのですが、全ての人に対してではありませんでした。James Campbell(Archie Campbell of Kilberry の息子)は Peter の多くの指摘に否定的だったと聞いています。Angus MacKay の信用を失墜させようとするのは、勇敢な人です。]

その James Campbell が鬼籍に入るのは 2004年の事。しかし、保守派は絶対多数。彼らを敵に回した Peter Cooke による Geroge Moss の代理戦争は終わりの見えない長期戦。そう簡単に決着が着くものではありません。そ の証拠に、この Stuart Letford の追悼文には更に次の様な下りがあります。

After the March 2015 edition of the Piping Times appeared, I received some flak from some of the more conservative members of the piping world for publishing Bridget MacKenzie’s last article.

[ "Piping Times 2015年3月号が発行された後、Bridget MacKenzie の最後の記事を掲載したことで、パイピング界のより保守的なメンバーから非難を受けたことがある。]

正直言って、ある程度は想定内なのでそれほど意外な気持ちはありません。でも、やっぱり落ち込みますね。なんとも、呆 れる程に救い難いパイピング界なのでしょうか。 Stuart Letford は勇敢な人です。敬意を表します。

彼の勇気に報いる為にも、次のパイプのかおり第47話では、この "Piping Times" 2015年3月号に掲載された "George Moss and the Fraser pipers" を 紹介(対訳)する事にしましょう。⇒ パイプのかおり第47話