第60話(2024/2)

JOHN MACFADYEN MEMORIAL LECTURE 1999

Behind

the Lines: Scholars, Writers, Pipers

"Piping Times" Vol.51/No.10-1999/7〜Vol.51/No.12-1999/9

"Piping Times" の誌面を 30年後に振り返る作業を、2007年〜2022 年(1977年〜1992年相当)の15年間続けました。そして、2022年秋に全て の "Piping Times" 等がデジタル化された事を受け、 2022年秋以降はそれらのデジタル版を通して、それ以外の期間の "Piping Times" 等を 振り返る作業がライフワークと なっています。デジタル化された直後は、1977年以前の(それも自分が生まれる前のかなり古い)記事に目を通す事 が多かったのですが、ここ最近のマイブームは《現代からの遡り》です。

1977年以前、20世紀半ばのピーブロック界は専制統治が盤石な時 代。…ですが、浅薄な自分にとっては特段その事を意識しなければ、実りの多い記事は多々有ります。一方で、21世紀に 入ってからのピーブロック界は、急速に民主化。…と同時に、その事に目覚めた私が最近気に なっているのが、20世紀半ばの専制制度が徐々に民主化されて行くその《過程》です。つまり、言うなれば『ピーブロック近代史』。現代から徐々に時代を遡 りつつその変遷を確かめていくのは、極めて興味深い作業です。そんな視点で紹介してき た、近年の「パイプのかおり」各話は、ピーブロック近代史を構成してきた生き証人たちによ る証 言集とも言えるでしょう。新たな情報を インプットする度に、それまで断片的に知っていた様々な情報が次々と繋がり、点が線になり、線が面になる、そんな感覚があります。そしてその結果、最近で はピーブロック近代史の全体像が、朧げながらもそれなりに俯瞰できる様になった気がします。

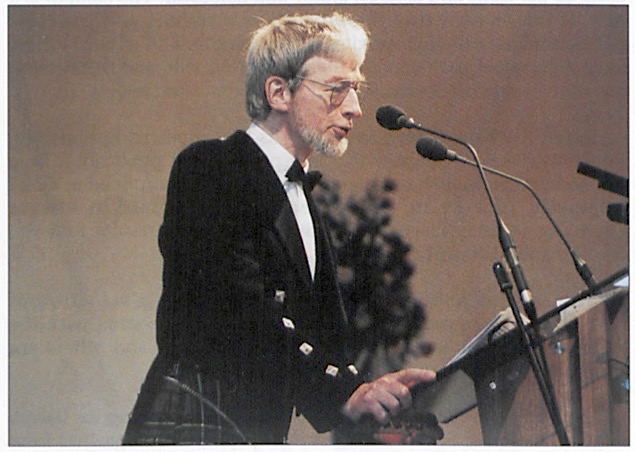

今回紹介するのは、 前回のパイプのかおり第59話に 続いて、John MacFadyne Memorial Lecture の講演録。1999年の Roderick D. Cannon 博士による講演です。1938年生まれの Cannon は当 時61才。その落ち着いた風貌と共に、これまで様々な記事や本の緻密な論述を思い起こせば、正に科学者・研究者を絵に描いたような、知的で沈着冷静な人物 だという事は 想像して余りあります。

近代のピーブロック愛好家には学者や医者などインテリ層が多く見られますが、全てが温厚な人物ばかりかというと、必ず しもそうではありません。最も卑近な例はかの Seumas MacNeill でしょう。この方も長年大学で教鞭をとっていたれっきとした科学者ですが、ひとたび頭に血が上る様な出来事に遭遇すると、歯に絹を着せぬ言葉でその対象を 口 撃をするのはご存知の通り。また、これまで紹介した民主改革派の論客の中にも、それなりに辛辣な言葉で過去の圧政を暴き 出す、と言った例も多々あります。私自身が頭に血が上りやすい人間なので、どちらかと言うと、その様な辛辣な改革派の言 葉に対して、大きな拍手をしたくなってしまうのも、それまた事実。

しかし、Cannon 大先生は違います。いつ何時も沈着冷静そのもの。今回の講演はいつもの様な自身のピーブロックに関する研究成果を発表する内容ではなく、これまでピーブ ロック界に関 わって来た様々なキャラクターの果たした役割り、現在のピーブロック愛好家が遍く被っている様々な恩恵をもたらしてい るその人々の尽力について概観する内容です。登場人物の功績を称える事こそあれ、その人物にたとえ同感できない側面が あったとしても、決して貶す様な言葉を使う事なく、淡々とその人物の有り様を伝えています。

この講演内容を読んで、点が繋がって線になっていた各種情報が、一気に絡みあってクモの巣状(ウェッブ状)に繋がった 様な気がしました。これまで紹介して来た様に、個々の《証言》そのモノを読むのとは一味違って、各《証言》の立ち位置や 読み解き方の解説し てくれている、と言う感じです。

講演録とは言え、例によって Cannon 大先生のその他の論文よろしく、各所に(総数53個にも及ぶ!)索引番号が振られて、各号文末の参照文献等一覧も膨大です。ウェブ上でアクセス可能な情報 や、 既にこのサイトのコンテンツとしてアップしている情報については、日本語訳の該当索引にリンクを張ってありますが、その 他については、デジタル版オリジナル各号の文献等一覧を参照願います。

では、心してお目通しあれ…。

| 原 文 |

日本語訳 |

|---|---|

| Part1 【Vol.51/No.10-1999/7- P24】 |

|

| My title has a

double meaning. I chose it because I want to

draw attention to some of the less prominent

individuals in the world of piobaireachd - the

writers and scholars who worked behind the lines

to supply the music that we hear today; and who

now are beginning to go behind the lines in

another sense, asking new questions about the

interpretation of the music. It's a big theme, and in one lecture I can’t do more than mention a few people, and touch on a few issues. As for the people I can only apologise to all those l have to leave out: as for the issues, I shall be asking questions rather than giving answers, but I don’t apologise for that. In fact it’s my belief that at the present time piping would be all the better for a few more questions, and a few less answers, than we have had until now. My story is in four chapters. In the first chapter I will look at some of the pioneers who first wrote down the music which they themselves had learned entirely by ear. In the next I will say something about what happened as a consequence of this writing. Then I will go on to talk about people who have extended our knowledge of piping, by applying professional skills that they had acquired in other walks of life. And in my fourth chapter I will say something about a new wave of understanding, which is coming from professional scholars in the academic world. |

私の今回の講演タイトルには二重の意味が込

められています。

私がこれを選んだ理由は、ピーブロックの世界ではそれほど著名ではない人々、つまり、今日私たちが耳にする楽曲を提供するために裏方とし働いた作家や学者

たちに注目してもらいたいからです。

そして、今、彼らは別の意味でこの楽曲の解釈について、裏方として新たな疑問を投げかけ始めています。 これは大きなテーマであり、1 回の講演では、ほんの数人の人物に言及し、僅かな問題に触れる程度しかできません。 今回の話題に含める事が出来なかった人々については、謝る事しかできません。様々な課題については、答えるのではなく質問するつもりですが、それについて はお詫びしま せん。 実際、現時点では、これまでよりも、いくつかの質問が増えて回答が減れば、パイピング界はさらに良くなるだろうと、私は確信しています。 私の話は4つの章で構成されます。最初の章では、耳だけで聴き覚えた音楽を初めて紙に書き留めた幾人 かの先駆者たちを見ていきます。 続いて、この楽譜記述の結果、何が起こったのかについてお話します。 次に、他の分野で習得した専門スキルを応用して、パイピングに関する知識を広げた人々についてお話しま す。 そして、第4章では、学術界の専門学者たちからもたらされている、解釈に関するニューウェーブについて 述べたいと思います。 |

| My first pioneer is

Niel MacLeod of Gesto. He was born about 1770

and was a tenant farmer in the North West of

Skye. In fact he came of an old family directly

descended from one of the earlier chiefs of the

clan, MacLeod of Dunvegan. His great service to us was that he cultivated the acquaintance of none other than John MacCrimmon, Iain Dubh, one of the last generation of the famous hereditary pipers. From the teaching of Iain Dubh, Niel MacLeod wrote down a collection of piobaireachd, entirely in the verbal notation called canntaireachd [1]. He never attempted to transcribe the tunes into ordinary music notation, and the only person who saw his manuscripts and tried to translate some of them didn’t make a very good job of it [2]. But fortunately for us, Niel MacLeod did succeed in getting some of his tunes published, and it is through his small book, printed in 1828, that we come nearest to knowing how any of the famous MacCrimmon pipers actually played [3]. We will hear one of these tunes in a moment, but first I want to comment a little on Niel MacLeod and what drove him to spend his time in recording this music. He certainly was a very strange man. As I just said, he was one of the minor gentry, directly descended from one of the earlier chiefs of the Clan MacLeod. During the Napoleonic Wars, he joined the Army as a junior officer, but his service was short, and seems to have consisted entirely of persuading other people to join up. In those days, rank in the army had to be purchased, either with money or with men. Niel MacLeod raised the numbers required to start out as an Ensign, and to be promoted to Captain, though by the time he got that far he no longer had a regiment, he was just listed officially as an “Independent” and ever afterwards he styled himself, as “Captain, half-pay, Independents”, as if that was something to be proud of. It seems that nobody liked him - unless perhaps John MacCrimmon did. He had boundary disputes with his neighbours including his chief, which was very unwise, since in the end he lost his land. After persistent attempts he got a new living under a Government scheme to promote the fishing industry in his part of Skye. But in this he was opposed by various people who didn’t trust him, including his own relatives. He ended up living in Edinburgh for much of the time, pursuing obscure legal disputes, which never came to anything. I see him as a lonely cranky figure, driven by obsessions, but for all that he was a pioneer and a benefactor to piping. Long after his death, a controversy arose about Gesto’s authority - that favourite word among pipers. His grandson, Dr Kenneth Norman MacDonald, mounted a strong propaganda campaign in his favour, and another faction, led by the piper John Grant, was equally passionate against him. The basis of the argument was whether Gesto was or was not a good piper himself: it seemed to be agreed on both sides that that was crucial to the case. The argument raged through the correspondence columns of the Oban Times, getting nowhere, until another Skyeman weighed in with some real evidence and a touch of common sense. His name was Myles Machines and he had heard stories that Gesto could indeed teach piping and pipers came to his house to learn. He even had some of the Gaelic phrases that he used in the teaching, and they tell us that Gesto at least knew some of the rudiments. His concluding comment was “that the men who gathered [at his house] learned more from each other than from himself” [4]. In other words he provided hospitality and a place where pipers could gather and be valued for what they did. I suggest that that is not a bad epitaph for a supporter of piping - a man who operated “behind the lines”. Gesto’s little book has its faults, but it stands out to me as a genuine record of what the old pipers actually sang. What I mean is that if it had been more perfect - and it could very easily have been tidied up - it would have been less convincing. That’s a problem that faces us whenever we try to play music from old sources. Sometimes we have to admit that the more neat and tidy the presentation, the less reliable it is as a record of the authentic tradition. Nevertheless, Gesto preserves some excellent tunes and settings which would have been lost if he hadn’t saved them. One is a tune we rarely hear nowadays, but which was once among the best known of all pibrochs: Cogadh no Sith, War or Peace. MacCrimmon’s version as noted by Gesto is elegant and quite short: it has a ground, a doubling of the ground, and just three variations, leumluath, taorluath and crunluath, followed by crunluath mach. Besides the music, Gesto left a note on presentation: he says the ground is to be repeated after each variation, but not “after the Crouluigh mach or last part.” |

最初の先駆者は、Niel MacLeod of Gesto

です。 彼は 1770年頃に生まれ、Skye 島北西部の小作農でした。 実際には、彼は MacLeod of Dunvegan

一族の初期のチーフの直系子孫である古い家系の出身でもありました。 私たちに対する彼の多大な貢献は、彼が有名な世襲パイパーの最後の世代の一人、他ならぬ John MacCrimmon, Iain Dubh との知古を育てたことでした。 Niel MacLeod は、Iain Dubh の教えに基づいて、カンタラックと呼ばれる、完全な口頭表記法でピーブロックのコレクションを書き留めたのです[1]。 彼はそれらの曲を通常の楽譜に書き写そうとは決してしませんでした。また、彼のマニュスクリプトを見 てその一部を楽譜化しようとした唯一の人物は、余り良い結果を出せませんでした[2]。 しかし、私たちにとって幸運なことに、Niel MacLeod は彼の曲のいくつかを出版することに成功。私たちは、1828年 に印刷された彼のこの小さな本を通じて、有名な MacCrimmon パイパーが実際にどのように演奏していたか、について知る事に最も近づいたのです [3]。 私たちは、これらの曲の一つをもうすぐ耳にする事になりますが、最初に Niel MacLeod 自身について、そし て彼がこの曲を記録することに時間を費やしたのは何故か、について少しお話したいと思います。 確かに彼はとても奇妙な男でした。 先ほど述べたように、彼は小さな地主の一人で、Clan MacLeod の初期のチーフの一人の直系の子孫でした。 ナポレオン戦争中、彼は下級士官として陸軍に入隊しましたが、その勤務期間は短く、もっぱら他の人たちに入隊するよう説得するだけだったようです。 当時、軍隊での階級は、お金か人員で買う必要がありました。 Niel MacLeod は少尉としてスター トし、大尉に昇進するために必要な人数を集めましたが、その地位に到達する頃にはもう連隊に所属せず、 公式に《無所属》としてリストされて、その後はずっとそのようなスタイルをとりました。 彼自身は《キャプテン、半給、無所属》とし自称し、まるでそれが誇りであるかのように振る舞っていました。 どうやら、John MacCrimmon に 好かれなかったとしたら、彼は誰にも好かれなかったようです。 彼はチーフを含む隣人と境界争いを起こしましたが、最終的には土地を失ってしまったので、これは賢明な行為であったとは到底言えません。 粘り強い努力の末に、彼はスカイ島の自らの地区に於いて、漁業を促進する政府の枠組みの下で、新たな生 計策を企てました。 しかし、これには彼自身の親戚を含む、彼を信頼しないさまざまな人々から反対されました。 彼は最終的に殆どの時間をエディンバラに住み、曖昧な法的紛争を追求しましたが、結局何の解決にも至りませんでした。 私は彼を強迫観念に駆り立てられた孤独で気難しい人物だと思っていますが、それでも彼はパイピングの先 駆者であり恩人です。 彼の死後かなり経ってから、Gesto の 権威、つまりパイパーの間で好まれている言語、についての論争が起こりました。 彼の孫である Dr Kenneth Norman MacDonald は、彼を支持する強力なプロパガンダ・キャンペーンを展開しましたが、パイパーの John Grant が率いる別の派閥は、 同様に熱意を持って彼に反論しました。議論のベースは、「Gesto 自身が優れたパイパーであったのか否か」という点。それがこの案件にとって最重要である という点では、双方の合意が得られていました。この議論は Oban Times の通信欄で激しく燃え上がりましたが、あるもう一人のスカイ島在住者が幾つかのリアルな証拠と少しの常識を持ち出して意見を述べるまで、堂々巡りしていま した。 彼の名前は Myles Machines。 彼は、Gesto が実際にパイピング を教える事が出来て、パイパーたちが彼の家に学びに来るという話を聞いていました。彼は彼が教える際に 使ったゲール語のフレーズもいくつか知っており、それは、Gesto が少なくとも基本原理は知っていたことを物語っています。彼の締めのコメントは、「(彼 の家に)集まった男たちは、自分からよりもお互いから学んだことの方が多かった」 [4]。つまり、彼は パイパーたちが集い、自分たちの活動が評価される集いの場を提供したのです。これは、パイピングの サポーター、つまり《ラインの裏側》で活動した人物のものとしては、悪くない墓碑銘だと思います。 Gesto のこの小さな本には欠点 もありますが、古(いにしえ)のパイパーたちが実際に 謳った真正な記録として、私にとってはかけがえの無い宝物で す。私が言い たいのは、もしそれがもっと完璧だったら(それは極めて容易に整頓できた事でしょうが)説得力が薄れてい ただろうということです。これは、古いソースから音楽を演奏しようとするときに常に直面する問題です。 時には、スッキリと整然とした表現であればあるほど、本物の伝統の記録としての信頼性が低くなってしま う ことを、認めなければなりません。 それにもかかわらず、Gesto は、 彼がそれらを保存しなければ失われていたであろう、幾つかの優れた曲やセッティングを保存しています。 その1つは、今ではめったに聴かれない曲ですが、かつてはすべてのピーブロックの中で最もよく知られて いた曲の1つ、Cogadh no Sith, War or Peace です。Gesto が記録した MacCrimmon のバージョンは優雅で非 常に短く、Ground、Ground の doubling、そして leumluath、taorluath、crunluath の 3つのバリエーション、その後に crunluath mach が続きます。 曲のほかに、Gesto は演奏表現 に関するメモを残しています。彼は、Ground は各バリエーションの後に繰り返されるが、「crunluath mach や曲の最後の部分の後」では繰り返されない、と述べています。 |

| Allan MacDonald is now

going to play the tune. I have asked him to play

the Gesto version, with the repetitions of the

ground. But in all other respects - and this

goes for all the performances you will hear

tonight - I have asked him to use his own

judgement entirely as to the interpretation of

what is written. Here he is now, Allan

MacDonald, to play War or Peace, Cogadh no

Sith [5]. |

これから、Allan

MacDonald がこの曲を演奏します。 私は彼に、Ground

の繰り返しのある Gesto

バージョンを演奏するよう依頼しました。 しかし、他のすべての点において(そしてこれは今夜聴くこ

とになる全ての演奏にも当てはまりますが)私は彼に、書かれている内容の解釈に関しては完全に彼自身の

判断を下すようお願いしました。さあどうぞ、 Allan

MacDonald による、War or Peace, Cogadh

no Sith をお聴き下さい[5]。 |

| Canntaireachd was a natural

way for pipers to communicate, at a time when

the tradition was still strong, but in a rapidly

changing world it had no future. By the 1830s, books of music were being published, and manuscripts passed around and copied. The speed with which this happened is remarkable, and we now know a good deal about it. This is due to research done by Iain Maclnnes, in his thesis written at Edinburgh University in 1988 [6] and by Ruaridh Halford-MacLeod in articles which he published in 1995 [7]. Iain and Ruaridh compiled lists of tunes played in the main piobaireachd competitions and compared them with the contents of the various books and manuscripts. In that way they could measure how swiftly the competition repertoire of piobaireachd was influenced by the publication of books. And it certainly was swift: Donald MacDonald’s book was published in 1820, and in the next four years, the twenty most popular tunes offered in the competitions at Edinburgh, included no less than eleven of the ones that were in the book. Angus MacKay’s book came out in 1838, and the effect was even quicker. More than that, quite a number of Angus MacKay’s tunes were already being played just before his book was published. Ruaridh MacLeod makes the very interesting suggestion that copies of the pages of that book were already circulating amongst pipers in advance of publication. So - a decisive change - over from oral to written tradition. Was that in fact a break with tradition; in other words did we lose something that can never be put back? Perhaps we did, but I will maintain that tradition is more robust than that: it changes its nature as time goes on, but it is still with us. One of the things we take great pride in is the fact that piping, and especially piobaireachd, has come down to us in an unbroken line. All the great players can claim to have been taught by other great players, in a series going back to the legendary past. That’s well known, but what’s perhaps less well known is that our written records also constitute a tradition in the same sense that knowledge has been handed down from one writer to another. There are some differences. The process of writing the music on paper took place in a rather short time, and it has a definite starting point. But if I quickly run through some names you will see why I call it a tradition. |

カンタラックは、その伝統がまだ根強く残っていた時代に

は、パイパーたちにとっての自然なコミュニケーション手段でしたが、急速に変化する世界では、その未来

はありませんでした。 1830年代までに、(印刷された)楽譜集が出版され、マニュスクリプト(手書き写本)が 回覧されコピーされるようにな りました。これらが起こったスピードは驚くべきもので、私たちは今では、それについてかなりのことを 知っています。これは、1988年にエディンバラ大学で書かれた Iain Maclnnes が執筆した研究論 文[6]と、 1995年に発表された Ruaridh Halford-MacLeod による研究論文 [7]で す。Iain と Ruaridh は、ピーブロックの主要なコンペティションで演奏された曲のリストを纏めて、それらをさまざまな楽譜集やマニュスクリプトの内容と比較しました。 そうすることで、ピーブロックのコンペティション・レパートリーが楽譜集の出版によってどれほど迅速に 影響を受けたか、を推し量ることができました。 そして、それは確かに迅速でした。Donald MacDonald の楽譜集は 1820年に出版され、その後4年間で、エディンバラのコンペティションで提供された最も人気のある 20曲の中には、その本に掲載された曲が少なくとも11曲含まれていました。Angus MacKay の楽譜集は 1838年に出版され、効果はさらに早く出ました。 それ以上に、Angus MacKay のかなりの数の曲 が、彼の楽譜集が出版される直前にすでに演奏されていました。 Ruaridh MacLeod は、その楽譜 集の幾つかのページのコピーが楽譜集の出版前に既にパイパーの間で回覧されていた、という非常に興味深 い示唆を しています。 つまり、口承から文書による伝承への、伝統の決定的な転換です。 それは実際、伝統を打ち破るものだったのでしょうか。言い換えれば、私たちは決して取り戻すことのできない何かを失ったのでしょうか? おそらくそうかもしれませんが、伝統はそれよりも強固である、と私は主張したいと思います。伝統は時間 の経過と共にその性質を変える物です。しかし、それはまだ我々と共に在ります。 私たちが非常に誇りに思っていることの一つは、パイピング、特にピーブロックが脈々と受け継がれてき たという事実です。すべての偉大なプレーヤーは、伝説的な過去に遡る一連の流れの中で、他の偉大なプ レーヤーから教えを受けたと主張できます。 それはよく知られている事ですが、恐らくさほど知られていない事は、知識が執筆者から他の執筆者へと受け継がれてきたのと同じ意味で、我々の文書化された 記録もま た、伝統を構成しているということです。 それらには幾つかの違いがあります。 紙に楽譜を書くプロセスはかなり短期間の内に行われた事、そして、それには明確な出発点がありました。 しかし、いくつかの名前をざっと見てみると、なぜ私がそれを伝統と呼ぶのか、理解できるでしょう。 |

| They start with Joseph

MacDonald, a young man born in Sutherland in

1739. In 1760 he wrote a full-length book on piobaireachd playing. It’s an amazing work, which for clarity and detail has never been surpassed. Joseph was only 21 years old when he wrote it, but he had been playing the pipes for about six years. When I first got to know Joseph, so to speak, I was the same age as he was. I felt a strong fellow feeling with him, and reading his book I could sense his excitement at being in possession of this body of knowledge which he was communicating for the first time to the outside world. Twenty years later, as a teacher, I felt what an excellent research student he would have made, diligent, observant, innovative. Twenty years further on again, and having worked over his book yet again for publication by the Piobaireachd Society [8], I can also see that he would be a bit of a handful, and he probably was so also to his parents. Just occasionally, his youthful enthusiasm gets the better of him. But still I would give him 99 per cent. He was a prodigy, not just in music, but in analysis and descriptive writing. He was equally industrious in noting down the airs of Gaelic songs, and it is almost certain that he also noted down a collection of piobaireachd. It’s a shame we haven’t got that collection, but we do have his instruction book, and from this we have enough to be able to reconstruct some of his playing. We shall be hearing more from him at the end of this lecture. |

まず手始めに、1739年に Sutherland に生まれた青年

Joseph MacDonald か

ら始めましょう。 彼は 1760年にピーブロック演奏に関する長編本を書きました。 これは驚くべき作品であり、明瞭さと詳細さに於いてこれを超える物はありません。 この本を書いたとき、Joseph は 弱冠 21歳でしたが、その時までに彼は約6年間パイプを演奏していました。 私が初めて Joseph を知った 時、私は彼と同じ年齢でした。 私は彼に対して強い仲間意識を感じましたし、彼の本を読んだ時、彼が初めて外の世界に伝え得る知識体系を手に入れた事に対する彼の興奮を感じる事ができま し た。 それから 20年後、私は教師として、勤勉で観察力に優れ革新的な彼が(もし、長生きしたとしたら)、どれほど優れた研究生になった だろうか、という事を感じました。 それからさらに 20年が経ち、ピーブロック・ソサエティー による出版 [8]に 向けて、彼の本にもう一度取り組んだ時、私は同時に彼が少々手のかかる人物で、おそらく両親にとっても そうであったであろう事が分かりまし た。 時折り、若々しい熱意が彼を圧倒してしまうことがある。 しかし、それでも私は彼に 99点を与えるつもりです。 彼は音楽面だけでなく、分析と記述の分野でも天才でした。 彼はゲール語の歌の旋律を記載することにも同様に熱心で、ピーブロックのコレクションを記録した内容はほぼ正確です。 私たちがそのコレクションを持っていないのは残念ですが、彼の教則本は残っているので、そこから彼 の演奏の一部を再構築するのに十分な量があります。 私たちは、この講義の最後に彼の遺した物を更に聴く事を予定しています。 |

| But my point here is that

(after some narrow escapes) Joseph’s book was

found and published as long ago as 1803. It was just about then that Donald MacDonald (no relation), in Edinburgh, began to interest himself in the task of writing down pipe music [9]. For various reasons it seems quite clear that Donald MacDonald studied Joseph’s book. In fact, though I can’t yet prove it, I suspect that Donald had a hand in finalising Joseph’s book for publication; and I am sure that he adapted his methods of writing. So it came about that Donald MacDonald published our first collections of pipe tunes, piobaireachd in 1820, small music in 1828, in a style of writing that is still essentially what we use today. |

しかし、ここで私が指摘したい点は、Joseph の本は(何度かの九死に一生を得

た後)1803年という、相当な年月を経た後に発見され、出版されたという事です。 ちょうどその頃、エディンバラにいた Donald MacDonald(血縁は無い)が、パイプ音楽を書き留める、という取り組みに興 味を持ち始めました[9]。 さまざまな理由から、Donald MacDonald が Joseph の本 を研究したことは明らかです。 実際、まだ証明はできていませんが、私は、Joseph の本を出版に向けて完成させる作 業に、Donald が関わったのでは ないかと推測しています。 そして私は、彼が自分の楽譜記載メソッドを、(Joseph の それに)適 応させたと確信しています。 そうして、Donald MacDonald は、 現在も私たちが本質的に変わらず使用しているスタイルで記載された、我々にとっての最初のパイプ音楽コ レクション(1820年にピーブロック、1828年にライトミュージック)を出版することになったので す。 |

| Another young man, Peter

Reid, apparently learned music writing from

Donald MacDonald; and then at the end of the

writing period came Angus MacKay, who collected

up everything that had gone before, indeed a lot

more of his own, and modified the writing system

into essentially what we have today. The book which he published was commissioned by the Highland Society of London, but he also compiled an enormous private collection of piobaireachd, in manuscript, and he made copies from this for the benefit of some of his friends and pupils. Those manuscripts were passed around, and tunes were recopied, and also published at various times in the nineteenth century, by William Ross, Donald MacPhee, David Glen and others. And of course they found their way into the present Piobaireachd Society collections, all in a direct line from their common source. That is what I mean when I say that writing itself, has become, with us, a tradition. |

もう一人の若者、Peter

Reid は明らかに Donald

MacDonald から、記譜法を学んでいます。

そして、楽譜記載時代の終わりに、Angus

MacKay

が登場しました。彼は、それまでに行われた全てのもの、実際には更に多くのものを収集し、記譜体系を本質的に今日私たちが使って持っているものに修正しま

した。 彼が出版した楽譜集は Highland Society of London からの委託によるものでしたが、彼はそれと同時に、ピーブロックの膨大な個人コレクションをマニュスクリプト(手書き写本)として編集し、友人や生徒たち のためにそれらの写しを作成しました。 これらのマニュスクリプトは回覧され、曲が再コピーされ、19世紀のさまざまな時期に William Ross、Donald MacPhee、David Glen らによって、楽譜集として出版されました。 そしてもちろん、それらはすべて共通の情報源から直接つながって、現在のピーブロック・ソサエティー 楽譜集に収まった訳です。記譜する事自体が、私たちと共に、伝統になったというのは、そういうことなの で す。 |

| Of the early writers of

music I’d like to mention one more: John

MacGregor. He came of a large family of

storytellers and musicians in Glenlyon. One of

his ancestors was remembered as lain Sgeulaiche,

John the storyteller, and in his own day the

family were prominent pipers, and won a large

proportion of the prizes in the early

piobaireachd competitions [10]. Our John MacGregor was piper to the Highland Society of London, and when the Society decided to take an initiative in writing down piobaireachd music, they delegated the job to him. He was to note down piobaireachds from one of the few remaining pipers who had been fully trained in the traditional schools - Angus MacArthur. There is no doubt that John MacGregor himself could have compiled a collection of tunes from his own knowledge, but in this case he was acting as scribe to someone else, an even more difficult job, I would think. Nowadays anyone attempting such a thing would simply switch on a tape recorder, encourage the informant to play, sing and talk as naturally as possible, then go away and sift the results, playing each little bit over and over to be sure of getting it right. Nothing so easy was possible in those days. Sometimes the tune would be one that MacGregor knew already, more often possibly not, because they do seem to have gone a bit out of their way to record tunes that hadn’t been written before. I wouldn’t like to say which would be harder - to record a new tune, or to take down one that was already known, because MacArthur’s way of the tune would be different from MacGregor’s and I take it for granted that MacGregor’s aim was to preserve MacArthur’s music as faithfully as he could. We do get a few clues to the methods and difficulties, from our study of the manuscript itself. From the way the notes are spaced on the paper it looks as though the basic melody was noted first, then the grace notes were put in afterwards. Sometimes the space for the gracenotes is a bit large, and in other places they have had to be squeezed in. Some of the gracenote movements are written in different ways in different places and it looks as though John MacGregor was feeling his way as to how best to write them. Since I assume that John MacGregor was not new to the business of writing pipe music, and we are told that Angus MacArthur played pretty consistently, I suppose that John had to have more than one try at writing down what was wanted. Indeed one tune is written out twice, first as a rough draft, then again as more of a fair copy. The manuscript was meant to be published, but it never was published, and among the possible reasons for that is one that I think tells us something about John MacGregor and what he was trying to achieve. It’s a question of notation: as every piper knows, Scottish bagpipe music is always written in the same position on the five lines of the music staff. The note which is played with six fingers on the chanter is called A, and is written as A on the stave. But John MacGregor wrote it five tones lower down, as if it was D. Why did he do this? I think there is no mystery. Obviously John MacGregor knew the note was A, but his system of writing was in line with what was already being done for other wind instruments, and in fact is still done today. Flutes and fifes are made in different sizes and sound at different pitches, but the music is written so that when you put your fingers in a particular position, say six fingers on the pipe and the little finger off, the note is written as D, even though it may actually be A, B, C, G or whatever, depending on the instrument. For anyone who plays more than one instrument, it obviously makes it easier to transfer from to another. With John MacGregor’s system, the bagpipe fitted into the scheme of things. In writing his music he had his eye also on the wider world. |

初期の楽譜記述者についてもう一人触れたいと思います。John MacGregor です。 彼は

Glenlyon の語り部であり音楽家であった大家族の出身でした。 彼の祖先の一人は、lain Sgeulaiche(John

the

storyteller)という呼称で記憶されており、彼の時代には著名なパイパー一家として名を馳せ、最初の頃のピーブロック・コンペティションに於い

て、賞の大半を獲得しました[10]。

私たちの John MacGregor は Highland Society of London のお抱えパイパーでした。そして、ソサエティー が「ピーブロックの音楽を譜面にする」という取り組みに率先して取り組むことを決定したとき、彼らはそ の仕事を彼に委任しました。 彼は、伝統的なスクールで十分な訓練を受けた数少ない生き残りのパイパーの一人、Angus MacArthur のピーブロッ クを書き留めることになっていました。John MacGregor 自身が自分の知識に基づいて楽譜集を編纂できた可 能性は疑いありませんが、この場合、彼 は他人の知識の筆記者としての役割に徹する訳ですから、更に困難な仕事だったと思います。 今日では、そのようなことを試みようとする人は誰でも、単にテープレコーダーのスイッチを入れ、情報 提供者にできる限り自然に演奏し、歌い、話すよう促し、その後立ち去り、結果をふるいに掛け、少しずつ 何度も繰り返し再生して、正しい事を確認するだけです。当時はそんな簡単な事は出来ませんでした。 時にはその曲は MacGregor がすでに知っていた曲であることもあったでしょうが、恐らくそうではない事の方が多かったでしょう。な ぜなら、彼らは以前に書かれていない曲を書き留めるために少し混乱したようだからです。 新しい曲を書き留めるのと、すでに知られている曲を書き留めるのと、どちらが難しいかを断言したくはありません。なぜなら、MacArthur のやり方は MacGregor のそれとは異なるであろうし、MacGregor の目的が MacArthur の音 楽を可能な限り忠実に 保存する事であるのは、当然だと思うからです。 私たちはこのマニュスクリプト自体の研究から、その方法と困難について、幾つかのヒントを 得る ことができます。 譜面上での音符の配置方法から、基本的なメロディーが最初に記され、その後装飾音が挿入されたように見えます。 装飾音のスペースが少し広い場合もあれば、押し込む必要がある場所もあります。装飾音の動きの一部は、 さまざまな場所でさまざまな方法で書かれており、John MacGregor がどのようにそれらを書くのが最善であるかについて、自分の やり方を模索しているように見えます。John MacGregor はパイプ音楽を譜面化するという仕事が初めてではなかったと 思いますし、Angus MacArthur は かなり一貫して演奏したと伝えられているので、John は求められていたものを書き留めるのに、複数回の試行が必要だったのではないかと思いま す。 実際、1つの曲が 2回書き下ろされています。最初は荒い下書きとして、そして、次にもう一度清書しています。 このマニュスクリプトは出版される予定だったのですが、結局出版されませんでした。考え得るその理由 の中の一つに、John MacGregor に ついてと、彼が達成しようとしていた事を物語っているものがあると思います。 それは記譜法の問題です。パイパーなら誰でも知っているように、スコットランドのバグパイ プ音楽は常に五線譜の同じ位置に書かれます。 チャンター上面6本の指を押さえた音は Aと呼ばれ、五線譜には Aと書かれます。 しかし、John MacGregor は、あたかも Dであるかのように、5 音下げてそれを書きました。なぜ彼はこのようなことをしたのでしょうか? 私はそれに謎は無いと思います。 John MacGregor 明らか にその音が Aであることを知っていましたが、彼の書き方は他の管楽器ですでに行われていたものと一致しており、実際に今日でも行われています。フルートとファイフは さまざまなサイズで作られ、さまざまなピッチで鳴りますが、楽譜は指を特定の位置に置くと、たとえば 6 本の指をパイプに置いて小指を離した場合、その音は楽器によっては実際には A、B、C、G などであっても、その音は Dと書かれています。 複数の楽器を演奏する人にとって、別の楽器への移行が明らかに簡単になります。John MacGregor のシステムで は、バグパイプがこのスキームに適合していました。 楽譜を書く際、彼はより広い世界にも目を向けていたのです。 |

| He wasn’t alone in this. A few years before, an amateur piper named Daniel Menzies had published a small book of instructions for beginners [11]. He too was a Perthshire man and he mentions the MacGregor pipers in his book; and he too wrote the music in the key of D. In two other places also I have found pipe tunes which can be traced to members of the MacGregor family, at around this same time, and they too are written in the same way [12,13]. Perhaps we could say it was a family tradition. | これは彼だけではありませんでした。この時から数年遡る頃、Daniel Menzies というアマチュアパイパーが、初心者向けの小さな教則本を出版していました [11]。 彼も Parthshire の人間で、本の中でもパイパー MacGregor 一族 について言及しています。 そして、彼も Dのキーで楽譜を書きました。他の 2つの場所でも、ほぼ同時期に MacGregor 一族のメンバーに遡ることができるパイプ・チューンを見つけましたが、それらも同じ方法で書かれていま す[12,13]。 おそらくそれは一族の伝統だったと言えるでしょう。 |

| I mentioned that the

MacArthur MS was never published. Only now is

the project of publishing the original

manuscript under way - a project sponsored by

the same John MacFadyen Trust who have organised

this evening. Some of the tunes are played

today, in adapted forms, but a fair proportion

of them are still comparatively unknown. It is one of those lesser known tunes that we will hear now, played by Andrew Wright. The tune is called The Bard’s Lament, or Cumha a’ Chleirich. It’s a most unusual tune with only one variation - no Taorluath or Crunluath, and the variation too is melodically unlike any of the others we know. Among his many piping activities Andrew has studied the whole of the MacArthur manuscript closely [14] and although he is going to follow the setting written by John MacGregor, I have asked him to use his own judgement entirely as to how to interpret the score. The Gaelic name, Cumha a’ Chleirich, can be translated as Lament for the Cleric or Lament for the Writer. If I had given this lecture a Gaelic title it would have been Failte nan Clkireach, Salute to the Writers. Tonight we are celebrating writers and the name of this tune reminds us that book-learning was an honoured profession in the Highlands even in the days when the oral tradition also was alive and well. Here now is Andrew to play the Lament for the Writer [15]. |

私は、MacArthur MS

はこれまで出版される事はなかったと述べました。

そして漸く現在に至り、オリジナルのマニュスクリプトを出版するプロジェクトが進行中です。このプロジェクトは、今夜の講演を主催したのと同様に

John MacFadyen Trust が後援するプロジェクトです。

一部の曲は今日でもアレンジされ形で演奏されていますが、そのかなりの部分はまだ比較的知られていません。

(⇒参照) 私たちがこれから聴く曲は、Andrew Wright が演奏する、あまり知られていない曲の 1つです。 この曲はThe Bard's Lament、または Cumha a' Chleirich と 呼ばれています。 この曲は、Taorluath も Crunluath 無く、バリエーションがたった 1つだけの、極めて珍しい曲で、そのバリエーション自体もメロディー的には私たちが知っている他の曲とは異なります。 彼の多くのパイプ活動の中で、Andrew は MacArthur マニュスクリプト全体を仔細に研究しており [14]、彼は John MacGregor によって書かれたセッティングに従うつもりですが、スコアをどのように解釈するかについては、私は完全に自分の判断に従うように彼にお願いしました。 ゲール語のタイトル Cumha a’ Chleirich は、Lament for the Cleric(聖職者)、又は Lament for the Writer(執筆者)と訳せます。 もし私がこの講演にゲール語のタイトルを付けていたら、Failte nan Clkkireach、Salute to the Writers というタイトルになっていたでしょう。 今夜、私たちは執筆者たちを祝福しています。この曲のタイトルは、口承が健在だった時代に於いても、ハイランドでは、机上の学問が名誉ある職業であった事 を思い起こさせます。 さあどうぞ、Andrew に よる Lament for the Writer をお聴き下さい[15]。 |

| Part 2 【Vol.51/No.11-1999/8 - P49】 |

|

| Now I come to my second

chapter. When the first writers had done their

work, we had well over three hundred pibrochs in

book or manuscript form. One of the results of

this was that piobaireachd became accessible to

the outside world. We pipers are so used to

thinking of the non-piping world as basically a

hostile environment that I would like to pause a

moment and mention a few non-pipers who came to

pipe music through the medium of writing, and in

their turn did us a service. |

さて、第2章に入ります。

最初の執筆者たちが仕事を終えたとき、私たちは書籍またはマニュスクリプトの形で、300曲を遥かに超えるピーブロックの楽譜を手にしました。

この結果の 1つは、ピーブロックが外部の世界にアクセスできるようになったことです。

私たちパイパーは、パイピング界以外の世界を基本的に敵対的な環境であると考えることに慣れているので、ここで少し立ち止まって、文書という媒体を通じ

てパイプ音楽を演奏するようになり、私たちに奉仕してくれた、パイパー以外の何人かの人々について触れ

たいと思います。 |

| One of them was Colin

Brown, a lecturer in music at Anderson’s

College, Glasgow. Anderson’s College later

became the Glasgow and West of Scotland

Technical College and is now the University of

Strathclyde. Colin Brown was a lecturer in

music: his full title was Euing Lecturer on the

Science, Theory and History of Music.

Considering that the college was founded to

teach practical subjects like commerce,

engineering and applied science, I think it says

a lot about the Scottish Education system that

the arts were so highly valued as well.

Certainly Colin Brown was a fine ambassador for

Scottish music: in 1883 he published a superb

book of Scottish songs and music, entitled “The

Thistle” [16]. I understand he was actually an

Englishman - at any rate he was born in

Liverpool in 1817 [17]. Maybe that enabled him

to look at the music with a fresh eye, or I

should say hear the music with a fresh ear. His

book ranged over the whole spectrum of Scottish

traditional music as it was at that time, songs

by Burns and others; fiddle tunes; ballads, and

pipe tunes. He considered that many of the old Scots tunes had been spoiled by arrangers who tried to force them into the framework of the classical music theory of the day. He was well ahead of his time, insisting on going back to the original melody and appreciating the subtlety with which the old composers got their effects using a restricted scale of notes. |

そのうちの1人は、グラスゴーのアンダーソン大学で音楽の講師をして

いる Colin Brown でし

た。

アンダーソン大学は後にグラスゴー・アンド・ウェスト・オブ・スコットランド工科大学となり、現在はストラスクライド大学となっています。

Colin Brown は音楽の講師

でした。正式な肩書は「音楽の科学、理論、歴史に関する Euing 講師」でした。

この大学が商業、工学、応用科学などの実践的な科目を教えるために設立されたことを考えると、芸術も同様に非常に高く評価されていたということは、スコッ

トランドの教育システムについて多くを物語っていると思います。 確かに Colin Brown はスコットランド音

楽の優れた大使でした。1883年に彼は "The Thistle"

というスコットランドの歌と音楽を集めた素晴らしい本を出版しました[16]。

彼が実際はイギリス人だったということは理解していますが、いずれにせよ、彼は

1817年にリヴァプールで生まれました[17]。そのおかげで彼は音楽を新鮮な目で見ること、あるいは新鮮な耳で聴くことができたのかもしれませ

ん。 彼の本は、Burns

の歌やその他から、フィドルチューン。

バラッド、パイプチューンまで、当時のスコットランドの伝統音楽のあらゆる分野に及んでいました。 彼は、スコットランドの古い曲の多くは、当時のクラシック音楽理論の枠組みに強制的に押し込めようと した編曲家によって台無しにされたと考えていました。 彼は時代をはるかに先取りしており、オリジナルのメロディーに戻ることを主張し、古い作曲家が限られた音階を使用して優れた効果を生み出した繊細さを、高 く評価していました。 |

| Maurice Lindsay, writing in

Grove’s Dictionary of Music (1954) was another

who came to piobaireachd by way of the printed

page. In an excellent article on Scottish music,

he dealt with piobaireachd, in a way that

suggests to me that before being commissioned to

write he had known little about it, but simply

by reading the music he had come to understand

how piobaireachd melody works, and how strong is

the range of emotions conveyed by different

types of tune, gatherings, salutes, laments. |

Grove's Dictionary of Music (グロー ブ音楽辞典 /1954年) に執筆した Maurice Lindsay も、印刷され たページを通じてピーブロックに辿り着いた一人です。 スコットランド音楽に関する優れた記事の中で、彼はピーブロックについて取り上げており、作曲を依頼される前はピーブロックについてほとんど知らなかった 彼が、単に楽譜を読んだだけで、ピーブロックのメロディーがどのように機能するか、そして、様々な種類 の曲調、Gathering、Salute、Lament によって伝えられる感情のレンジがどれだけ強いか、を理解するようになった事が示唆されています。 |

| In the 1940s, a Scottish

musician and writer, Donald Main, was studying

piobaireachd with a view to developing his own

compositions in classical vein. He was a fervent

Nationalist, and I suppose he felt himself to be

in the tradition of Grieg, Bartók, Copland and

others, who absorbed the folk music of their

respective countries and synthesised it into

something new in the classical tradition. Donald

Main died in 1951[18] ; and I must admit I

haven’t heard any of his compositions. But his

writings, in a number of periodicals show how

well he had understood principles of

piobaireachd composition and they have a good

deal to teach us today [19-21]. Finally - and there are others too - there was Francis George Scott, a better known Scottish composer whose works also owe something to the techniques and effects of pipe music [22]. |

1940年代、スコットランドの音楽家で作家の Donald Main

は、古典的な流れの中で自分の作品を発展させることを目的としてピーブロックを研究していました。

彼は熱烈な民族主義者で、それぞれの国の民俗音楽を吸収し、それを古典的な伝統の中で新しいものに統合した、グリーグ、バルトーク、コープランドらの伝統

の中に自分が居る、と感じていたようです。 Donald

Main は 1951年に亡くなりました[18]。

そして、私は彼の作品を一曲も聴いたことがない事を認めなければなりません。

しかし、多くの定期刊行物に掲載された彼の著作は、彼がピーブロックの作曲原理をいかによく理解していたかを示しており、今日の私たちに、多くの事を教え

て くれます[19-21]。 最後に(そして他にもいますが)、Francis George Scott はスコットランドの作曲家としてよく知られており、彼の作品もパイプ音楽の技術と効果に負っている部分があります。 |

| While these and other

musicians were putting out good propaganda for

the piobaireachd, their reception in the piping

world varied greatly. Colin Brown seems not to

have been noticed at all; Donald Main was seen

by some pipers at least as an enemy; but Francis

George Scott was listened to with respect. At

least one of his publications is a lecture which

he was invited to give at the College of Piping

[23], and some of his ideas can be traced in the

theories which Seumas MacNeill put forward about

the scale of the bagpipe chanter [24,25]. |

これらやその他の音楽家が、ピーブロックの良いプロパガンダを発信し ている一方で、パイプ業界における彼らの受け止め方は大きく異なりました。 Colin Brown はまったく注目されて いなかったようです。 Donald Main は一部のパイパーたちからは少なくとも敵視されていた。 しかし、Francis George Scott の話は敬意をもって耳を傾けられました。 彼の出版物の少なくとも 1つは、彼が College of Piping で行うよう招待された講演であり[23]、 彼のアイデアの一部は、バグパイプ チャンターの音階に関して、Seumas MacNeill が提唱した理 論に遡ることができます[24, 25]。 |

| But making piobaireachd

available in writing had another effect, closer

to home. A document, any document, in writing is

very different from something handed down

entirely through memory. It loses a lot of

course, and has to be reconstructed every time,

in the reader’s imagination. But it also gains

something, in that it sets the mind thinking and

comparing. Why do some tunes seem to come out in regular lines like poetry and some not? Why do different writers express the same tune in totally different types of gracenotes? If two tunes are similar, but not quite the same, are they versions of each other? What does that question even mean? These were questions that could be asked once the music had been committed to writing, and which wouldn’t have arisen before. And they were not just academic questions. If a tune is somehow “wrong”, surely we should put it right? And what if the piobaireachd as a whole had somehow taken a wrong turning? |

しかし、ピーブロックを書面で利用できるようにすること

で、より身近な別の効果が得られました。どの文書であっても、文書で書かれたものは、完全に記憶を通し

て伝えられるものとは大きく異なります。もちろん、それは多くを失い、読者の想像力の中で毎回再構築す

る必要があります。しかし、それはまた、考えたり比較したりする心を働かせるという点で、何かを得るこ

ともあります。 詩のように規則正しい曲調で出てくる曲とそうでない曲があるのはなぜですか? なぜ異なる作者が、全く異なるタイプの装飾音で、同じ曲を表現するのでしょうか? 2つの曲が似ていても完全に同じではない場合、それらはお互いのバージョンでしょうか? その質問は一体どういう意味なのでしょうか? これらは、音楽を書き留める事に取り組んだからこそ、湧いてきた質問であり、以前は起こらなかったで しょう。 そしてそれらは単なる学術的な質問ではありません。 曲が何らかの形で「間違っている」場合は、それを正しく修正する必要がありますか? そして、ピーブロック全体が何らかの形で、間違った方向に進んでいたらどうなるでしょうか? |

| So it came about that from

about the middle of the nineteenth century, a

small but growing number of people began to ask

these sorts of questions: and most of them were

pretty clear in their minds that they also had

the answers. There was John MacLennan, father of G. S. MacLennan and D. R. MacLennan. He was an early collector of manuscripts and he became convinced that pipers in his time had lost their way. He was sure that piohaireachd should be played in regular time and he argued this in two books which he published in 1907 and 1925 [26,27]. Dr Charles Bannatyne [28] also collected manuscripts. He proposed radical interpretations of canntaireachd [29] and he attempted to revise pipe music notation to bring it more into line with classical conventions [30]. There was Simon Fraser, in Australia [31]. He claimed to have inside information, and he said that techniques of playing variations had been forgotten. And there were many more - A. K. Cameron [32], John Grant [33], J. D. Ross Watt [34], Willie Gray [35], George Moss [36]. Some of them wrote books; most of them wrote letters to newspapers; everyone knew about them and what they were saying, but almost without exception they were ignored. Yet these were intelligent men and they had applied their minds honestly to questions which needed to be asked. Where did they go wrong? Some people were not afraid to tell them where they had gone wrong. They were not good pipers, it was said; or not taught by the right people; or not Gaelic speakers; or in a word not in the mainstream of the piping world. Any of these things could be true about any of them but I am going to suggest that there was another and simpler reason why their efforts were bound to fail. To do this, I will turn to another writer and student, who would also be quite fairly classed with these sceptics, but who pointed the way forward to a much more profitable style of discussion. |

そこで、19

世紀半ば頃から、少数ではあるものの、この種の質問をする人が増え始めました。そして、彼らの多くは、

自分自身がその答えを持っている、とかなり明確に心の中で思っていました。 G. S. MacLennan と D. R. MacLennan の父、John MacLennan がいました。彼は初期のマニュスクリプト収集家であり、当時のパイパーたちは道を見失っている、と確信するようになりました。彼はピーブロックは規則正 しいタイミングで演奏されるべきだと確信しており、1907年と 1925年に出版した 2つの本でこれを主張しました [26, 27]。 Dr Charles Bannatyne [28]もマニュスクリプトを収集しました。 彼はカンタラックの過激な解釈を提案し[29]、パイプ音楽の記譜法を改訂して古典的な慣習に近づけようと試み ました[30]。 オーストラリアには Simon Fraser [31] がいました。 彼は内部情報を持っていると主張し、バリエーションを演奏するテクニックは忘れ去られていると述べました。その他にも、A. K. Cameron [32]、John Grant [33]、J. D. Ross Watt [34]、Willie Gray [35]、George Moss [36] など、たくさんの人がいました。 彼らの中には本を書いた人もいました。 彼らのほとんどは新聞に手紙を書きました。 誰もが彼らのことと彼らが何を言っているかを知っていましたが、ほぼ例外なく無視されました。 しかし、彼らは聡明な人々であり、尋ねるべき質問に対して誠実に自分の考えを当てはめていました。 彼らのどこが間違っていたのでしょうか? どこで間違ったのかを恐れずに話す人もいました。 彼らは「良いパイパーではなかった」と言われました。 あるいは「適切な人から教えられていない」「ゲール語話者では無い」、言い換えれば「パイピング界の主流では無い」という言われ方。 これらの事はいずれも真実である可能性がありますが、私は、彼らの努力が必然的に失敗に至った、別のよ り単純な理由があったことを示唆したいと思います。 これを行うために、私は執筆者であり学生であった別の人物に頼ることにします。この人もこれらの懐疑論者にかなり分類されるでしょうが、より有益な議論の スタ イルへの道を示してくれました。 |

| He wasn’t well known. He

wasn’t connected with leading pipers. He didn’t

even have access to the old manuscripts, just

the published books of piobaireachd, but in

spite of that he achieved remarkable results. His name was George F. Ross [37]. Like so many other piping students he lived and worked mainly in India, but his two books were published in Glasgow [38,39]. His first book, in 1926, has a short but splendid title: “Some Piobaireachd Studies”. I sometimes wonder, was this the first time those two words, “piobaireachd” and “study” had ever appeared together in print? Did they put people off? I suspect they did, because when I came on the scene more than thirty years later, it was still possible to find copies on sale in the bookshops. Those who were not put off had a treat in store. Apart from anything else the books are extremely well designed and printed. What was revolutionary was the layout. The pages are wide and they open out to more than two feet across. The whole ground of a tune, or a whole variation, could be written out in a single line across the double page. Different versions could be written one under the other, and to compare one with another it was just a matter of sliding them along until corresponding parts were in line with each the other, leaving gaps wherever anything seemed to have got missed out. In this way it was possible to decide between versions, or correct them. The important thing, though, and I can’t stress this too much, is that in Ross’s books we, the readers, can see what he has done, and we are free to agree or disagree with it. Not everything that he did would be accepted today. There was a lot of unpublished information that we have and he didn’t, and sometimes he changed things on principle, following some theory, when the facts didn’t warrant it. But there is no harm in it when we ourselves can see what has been done. That was the new lesson that Ross taught us. One of G. F. Ross’s achievements was to successfully edit a tune which had been printed in Niel MacLeod of Gesto’s collection of canntaireachd and also noted by Angus MacKay in his manuscript. But most unusually, Angus MacKay went astray in his presentation of the tune, writing it with three beats to the bar, whereas it makes much better sense with four beats. There can be no doubt that G. F. Ross got it right, and we can recognise the tune as one of several which use the basic melody, which we know as Duntroon. Now you can judge for yourself what a well-made piece it is, as Andrew Wright is back again to play it for us - Duntroon’s Salute [40]. |

彼はあまり知られていません。

有力なパイパーとの繋がりもありません。

彼は古いマニュスクリプトにさえアクセスできず、出版されたピーブロックの本しか入手できませんでしたが、それにもかかわらず、彼は驚くべき成果を達成し

ました。 彼の名前は George F. Ross [37]。 他の多くのパイピングを学ぶ学生と同様に、彼は主にインドに住み、そこで働いていましたが、彼の 2冊の本はグラスゴーで出版されました [38,39]。 1926年に出版された彼の最初の本は、"Some Piobaireachd Studies" という短いながら素晴らしいタイトルでした。 時々、「ピーブロック」と「研究」という 2つの単語が一緒に印刷されたのは、これが初めてだったのではないか、と思うことがあります。この2つの単語が人々を遠ざけたのでしょうか? 30年以上後に、私がこの世界に来たとき、まだ書店で販売されているのを見つけることができた事から、 恐らく、そうだったのだろうと思います。 躊躇しなかった人には、本屋でご褒美が用意されていました。 他のどの本(楽譜集)とも異なって、これらの本は非常によくデザインされ、印刷されています。 革新的だったのはレイアウトです。 ページは幅が広く、開くと幅が2フィート以上になります。 曲のグラウンド全部、またはバリエーション全部を、見開きページに1行で書き出すことができます。 異なるバージョンを上下に記述することができ、バージョンを比較するには、対応する部分が互いに一致するまでスライドさせて、何かが欠けているように見え る箇所に隙間を残すだけでした。 このようにして、バージョンを決定したり、修正したりすることができました。 しかし、重要なことは(いくら強調してもしすぎることはありません)、私たち読者は、Ross の本の中で彼が何をしたのかを見ることができ、それに同意するか反対するかは自由だということです。 彼がしたことすべてが今日受け入れられるわけではありません。現在の私たちが持っているのにも拘らず、 彼が持っていなかった未発表情報は沢山有り、事実がそれを保証しない場合、彼は理論に従って原則的に物 事を変更することがありまし た。 しかし、何が行われたかを私たち自身が確認できるのであれば、何も害はありません。 それが Ross が私たちに教えてくれた新しい教訓 でした。 G. F. Ross の 功績の 1 つは、Niel MacLeod of Gesto のカンタラック集に掲載され、Angus MacKay もマニュスクリプトで書き下ろしていた曲の編集に成功したことです。 しかし、最も奇異なことに、Angus MacKay はこの曲の表現法で道を踏み外し、4ビートのほうがはるかに理にかなっているのに、3ビートでこの曲を書いたのです。 G. F. Ross が正しく理解し たことに疑いの余地はなく、この曲は Duntroon として知られる基本的なメロディーを使用したいくつかの曲のうちの 1 つであると認識できます。 Andrew Wright が 再び演奏してくれるので、この曲がどれ程良くできた作品であるかを、自分の耳で確かめてください - では、Duntroon's Salute をお聴き下さい [40]。 |

| Part 3 【Vol.51/No.12-1999/9 - P41】 |

|

| We have now reached the

beginning of a new era in piping scholarship,

with critics who had been trained and earned

their living at some discipline, which they then

brought in to their piping. You could say, their

piping scholarship was a hobby, but it was a

hobby pursued to professional standards. This takes us directly to one of the giants of piping, Archibald Campbell, Kilberry. He was trained as a lawyer and spent much of his life practising law in the Indian Civil Service, becoming a High Court Judge, before he came back to teach at Cambridge University [41]. For over thirty years he was Music Editor of the Piobaireachd Society, and the books we still use are his monument. But I want to stress aspects of his work which are easily overlooked, in spite of the fact that he himself emphasised them clearly enough. The first is that in all his writings, he steered very clear of the myths and legends which other writers copied and embroidered, and which I must say quite frankly have done a lot to bring piping into disrepute. There were plenty of people in his day who were prepared to believe that piobaireachd as we know it dated back to some ancient period in the Celtic twilight. Kilberry brought it forward into the seventeenth century [42]. There were plenty of people wishing to believe that the MacCrimmons had carried on their college at Boreraig for up to five centuries. Kilberry was up to date with the current research which showed that their tenure had been comparatively brief, there being “always a tendency for the story teller to exaggerate antiquity” [43]. As regards the music itself, he suggested that piobaireachd had changed over time, tunes having been restructured from the simple song-like forms, into the more complex tune patterns that we have today; and he even discussed the possibility that the playing of piobaireachd might have changed, especially the tempo, becoming markedly slower over the past hundred years [44]. But the second aspect of Kilberry’s attitudes is one that is even less regarded. Both in professional life and in piping he was a judge and a figure of the establishment. Who would be more likely to impose his superior knowledge on the rest of the piping world, suppressing dissent, and enforcing the law? Certainly he had enemies who accused him of that kind of thing. By extension, the whole of the Piobaireachd Society could be seen as some sort of governing body of piping, making rules like a golf club or athletic association. And again there were people who thought that it was so, or that if not, it ought to be so. But if we read carefully what Kilberry wrote, we find that he thought of himself as a student, always trying to find out what the master pipers had said and done, and trying to follow them even against his own inclinations. James Campbell summed it up, in the preface to his edition of Archibald Campbell’s notebooks [45]: ... he had a lifelong distaste for seeking to dogmatise... a horror of being thought to be laying down the law.I wonder if I myself am making myself clear. I don’t for a moment suggest that Kilberry was always right. I think he was overinfluenced by the legacy of Angus MacKay, and not tolerant enough of varieties of old tradition. But his attitude was critical in the proper sense of that word and that is a lesson we can take from him, however we might disagree with him in detail. |

私たちは今、ある専門分野で訓練を受けて生計を立て、それを自分たち

のパイピングに持ち込んだ批評家たちによる、パイピング学問の新時代の始まりに辿り着きました。

彼らのパイピングの研究は趣味だったと言えるかもしれませんが、それはプロフェッショナルの水準を追求した趣味でした。 これは、パイピング界の巨人の一人、Archibald Campbell, Kilberry に直接つながります。 彼は弁護士として訓練を受け、人生の多くをインド公務員として法律実務に費やし、最後は高等裁判所の判事となり、その後ケンブリッジ大学で教鞭をとるため に戻ってきました [41]。 彼は 30年以上にわたってピーブロック・ソサエティーの音楽編集者を務めており、私たちが今でも使用している楽譜集は彼の記念碑です。 しかし、私は、彼自身がそれらを十分に明確に強調しているにもかかわらず、見落とされがちな彼の業績の 側面を強調したいと思います。 第一に、彼はすべての著作において、他の作家がコピーしたり誇張したりしていた、神話や伝説をきっぱ りと避けていたということです。率直に言って、これらはパイピングの評判を落とすのに多大な貢献をした と言わざるを得ません。 私たちが知っているように、当時は、ピーブロックの起源はケルトの黄昏の古代に遡ると、信じようとする人が沢山いました。 Kilberry はその起源の時間を進めて 17世紀に持ち込みました [42]。 MacCrimmon 一族が Boreraig に於いて最長で 5世紀に渡ってカレッジを続けてきたと、信じたい人は沢山いました。 Kilberry は、彼らの在職期間が比較的短く、「語り部は常に古めかしさを誇張する傾向」があることを示す、最新の研究を行っていました[43]。 音楽自体に関して、彼はピーブロックが時間の経過とともに変化し、曲が単純な歌のような形式から、今 日私たちが持つより複雑な曲のパターンに再構築されたと示唆しました。 そして彼は、過去 100年間でピーブロックの演奏が変化し、特にテンポが著しく遅くなった可能性についてさえ議論しました[44]。 しかし、Kilberry の態度の 2番目の側面は、さらに軽視されています。 職業生活においてもパイピング界においても、彼は裁判官であり体制側の人物でした。 自身の優れた知識を他のパイピング界に押し付け、反対意見を抑圧し、法律を執行する可能性が最も高い 人は誰でしょうか? 確かに彼には、彼のそのような面を非難する敵がいました。 拡大して言えば、ピーブロック・ソサエティー全体は、ゴルフクラブやスポーツ協会のような、規則を制 定するある種の統治機関とみなすことができます。そして再び、それがそうだ、或は、そうでないとしても こうあるべきだ、と考える人々がいました。 しかし、Kilberry の書いたものを注意深く読んでみると、彼は自分自身を学ぶ立場であり、常にマスター・パイパーの言動を 知ろうとし、自分の傾向に反してでも彼らに従おうとしていることがわかります。 James Campbell は、Archibald Campbell のノートブックの序文で次のように要約しています [45]。 ...彼は生涯、教条主義化しようとすることに嫌悪感を抱いていました... 法律を制定していると思われることへの恐怖でした。私自身、自分の考えを明確に出来ているかどうか、と思います。私は、Kilberry が常に正しかったとは、つゆ程も思っていません。 彼は Angus MacKay の遺産に過度に影響を受けており、さまざまな古い伝統に対して十分に寛容ではなかったと思います。 しかし、彼の態度は正しい意味での批判的なものであり、細部において彼の意見に反対であったとしても、それは私たちが彼から得ることのできる教訓です。 |

| My next critic is another

amateur scholar with professional attitudes.

Robin Lorimer was trained in literary studies,

and spent much of his career as an editor, and

eventually director of the famous publishing

house of Oliver and Boyd, in Edinburgh [46]. He

was one of the few who realised what a vast

contribution piping had to make to the

understanding of Scottish history and culture,

if only other scholars could be persuaded to

take it seriously. In 1940 he published a short article which formed a kind of preface to a book on piobaireachd which perhaps he could have written, though the programme he outlined for it was so wide that probably no one person could have done it in a lifetime [47]. But in the 1960s he achieved something which no piping scholar had done before, and published a study in depth of an aspect of piobaireachd, in a professional, academic journal. |

私の次の批評先は、プロとしての態度を持った別のアマチュア学者で

す。 Robin Lorimer は

文学研究の訓練を受け、キャリアの多くを編集者として過ごし、最終的にはエディンバラにある有名な出版

社 Oliver and Boyd のディレクターとして過ごしました[46]。

彼は、スコットランドの歴史と文化の理解にパイピングがどれほど多大な貢献をしなければならないかを理解した、数少ない一人でした。ただし、もしも他の学

者を説得して真剣に受け止めてもらていれさえすれば、ですが。 1940年に彼は、ピーブロックに関する本の序文のような短い記事を発表しました。おそらく彼ならこ の本を書くことができたかもしれませんが、彼が概説したプログラムは非常に広範であり、おそらく誰が一 生かけてもそれを行うことはできなかったでしょう [47]。 しかし 1960年代に、彼はそれまでパイピング学者が成し得なかったことを成し遂げ、ピーブロックの側面についての深い研究を専門的な学術雑誌に発表しました。 |

| Since you may well wonder

why that is so exciting, I would like to take a

few minutes to explain. The disciplines of academic research are not always understood outside the small world of the universities. There are some very strict conventions about how it is done, and even about what you can and cannot say. Evidence on every point has to be searched for and the search doesn’t stop until you have some real reason to think that it’s complete. You don’t read just a few of the things that previous people have written, you read them all. If you sift through old papers you say what you have sifted and where it is. If you interview pipers and other people with personal knowledge, you preserve your notes and tape recordings so other people can consult them later. And there are special techniques that apply to subjects like piping. Most of our written information is actually the record of oral tradition, but too often it has been written down by intermediaries who were not trained in these disciplines, so you have to try and distinguish what was really said in the first place, and what was tidied up and “improved” by a later editor. When all this is done you write it up as judiciously as you can, taking care not to let your speculations go too far beyond the established facts, and send it to be published in some monthly or quarterly journal. But even then your work is not over. It goes to a panel of judges. They read it and criticise it, and if they don’t like it, it doesn’t get published, in spite of all the hard work you have put in. If they are good judges they will send in a report telling you the mistakes they think you have made, or the evidence they think you have not considered. In the best case you have a chance to revise your work in the light of these criticisms, and finally the editor will accept it, and eventually it takes its place along with hundreds of other works of the same sort, on the shelves of reference libraries throughout the world. |

何故そんなに興奮するのか疑問に思われるかもしれませんので、まずそ

の点についての説明に数分掛けたいと思います。 学術研究の規律は、大学という小さな世界の外では必ずしも理解されているとは限りません。その方法 や、何 を言ってもいいのか、何を言ってはいけないのかについても、非常に厳格な規則がいくつかあります。 あらゆる点に関する証拠を探す必要があり、それが完了したと考える本当の理由が得られるま で、調査は停止しません。 前の人が書いたものをいくつか読むのではなく、全てを読みます。 古い書類をふるいに掛けたとしたら、何をふるいに掛けたか、それが何処に有るかを明らかにします。 パイパーやその他の個人的な知識を持つ人々にインタビューする場合、後で他の人が参照でき るようにメモやテープの録音を保存します。 また、パイピングなどの主題に適用される特別なテクニックもあります。 私たちの手にする文書化された情報のほとんどは、実際には口頭伝承の記録ですが、これらの 専門分野の訓練を受けていない仲介者によって書き留められていることがあまりにも多いため、最初に何が 実際に語られたのか、後の編集者によってどの様に整理され「改善」されたか を、区別するよう努める必要があります。 これらすべてが完了したら、自分の推測が確立された事実を大きく超えないよう注意しながら、できる限り慎重にそれを書き上げ、月刊誌または季刊誌に掲載す るために送付します。 しかし、それでもあなたの仕事は終わっていません。 それは審査員団に送られます。 彼らはそれを読んで批判しますが、気に入らない場合は、あなたが一生懸命努力したにもかかわらず、出版されません。彼らが優れた審査員であれば、間違いを 報告する報告書を送ってくれるでしょう。 あなたが作成したと彼らが考える証拠、またはあなたが考慮していないと彼らが考える証拠。 最良の場合には、これらの批判を踏まえて自分の作品を修正する機会があり、最終的に編集者がそれを受け入れ、結果として、他の何百もの同じ種類の作品とと もに、世界中の参考図書館の棚に置かれることになります。 |

| We might say, what about

freedom of speech? Who are these judges? Hasn’t

every opinion a right to be heard? The answer to

that is yes - and no. You certainly have a right to your opinions, but you have a responsibility to limit your opinions within the range of what the evidence allows. The reputation of the journal in which your work is published depends on the quality of its judging system; and in turn, your standing as a scientist or scholar depends on getting your work regularly into journals of high reputation. These disciplines are taught to research students in universities. The first big test is to write a thesis under the guidance of a senior scholar. If it satisfies a board of examiners, the student gets a higher degree with a title like MA or PhD. And if the student carries on in the academic profession he or she will do more research, independently, and publish it, and in turn become a supervisor of other students, a professor and an editor of learned journals. Does all this sound familiar? A bit like the profession of piping? A piper takes lessons and practises; takes part in competitions; goes on to more advanced teachers; wins prizes; gets the gold medal and clasps, becomes a teacher and eventually a judge. For the academic scholar, the degree is the gold medal, and the publications in scholarly journals are the clasps. And who reads these learned articles? The answer is, not many people read them at all. But those few will take them on board, and use them as a basis for further studies of their own. In this way, knowledge is built up bit by bit, and gradually it emerges in books or other media, and changes the way we look at the world. Of course I am describing an ideal scenario. Not all academic research is top quality, not all of it is equally relevant. And as for the judging... |

言論の自由はどうなのだろうか、と言う人もいるかもしれません。

この裁判官は誰ですか? あらゆる意見が聞かれる権利があるのではないでしょうか?

その答えは「はい」でもあり、「いいえ」でもあります。 確かにあなたには自分の意見を言う権利がありますが、証拠が許す範囲内で自分の意見を制限する責任が あります。 あなたの作品が掲載される雑誌の評判は、その審査システムの質に依存します。 そして、科学者または学者としてのあなたの地位は、評判の高いジャーナルに定期的に研究結果を掲載できるかどうかにかかっています。 これらの規律は大学の研究生に教えられます。 最初の大きなテストは、上級学者の指導の下で論文を書くことです。 試験委員会がそれを満足させた場合、学生は修士号や博士号などのより高い学位を取得します。 そして、学生が学術的な職業を続ければ、独立してさらに研究を行い、それを出版し、ひいては他の学生の指導者、教授、学術誌の編集者となるでしょう。 これらすべてに聞き覚えがないでしょうか? パイピングという職業に少し似ていませんか? パイパーはレッスンを受けて練習します。 競技会に参加します。 より上級の指導者の下に進みます。 賞品を獲得します。 金メダルやクラスプを獲得し、教師になり、最終的には審査員になります。 学者にとって学位は金メダルであり、学術雑誌への論文はクラスプです。 そして、これらの学術記事を誰が読むのでしょうか? 答えは、読んでいる人はそれほど多くない、ということです。しかし、それらの少数の人々はそれらを受け入れ、彼ら自身のさらなる研究の基礎としてそれらを 使用します。 このようにして知識が少しずつ蓄積され、徐々に本や他のメディアとして現れ、私たちの世界の見方を変えます。 もちろん、私は理想的なシナリオを説明しています。 すべての学術研究が最高品質であるわけではなく、すべてが同等に関連性があるわけでもありません。 そして審査の方はというと… |

| But somehow the system

works; a consensus is usually reached and the

experts usually know what to believe and what

not to believe. And if you agree with all that

you will understand why I say that it was such a

landmark in the history of piping when Robin

Lorimer’s two articles on piobaireachd appeared

in the quarterly journal Scottish Studies,

published by Edinburgh University; in 1962 and

1964 [48]. I am saying nothing here about their

content. They deal with a certain aspect of the

construction of piobaireachd, and my sole point

is, that from now on, no one else can usefully

contribute to that debate without taking full

account of those articles, whether to agree or

to disagree. And this I suggest, is the answer to the question that I posed earlier. Why did the sceptics of previous generations make so little impact? I believe it was not because they were wrong - I’m sure they weren’t always wrong. I suggest it was because their views were not controlled by the balanced and rigorous handling of the evidence, which is what we call scholarship, or scientific method. The old- time sceptic had made his mind up, and he was not going to change it just because somebody else had made his mind up in the opposite way. And while the opinionated few fought each other to the death in the letters to the Oban Times, the rest of the world got on with its business, which in this case was playing music and winning prizes. Genuine progress can be made with some of those questions which troubled the sceptics. But it needs patience, awareness of different possibilities, and above all, hard work. And this brings me to the final chapter in my story. In the last thirty years or so, professional scholars have begun to move in on the piping world, and we are beginning to feel the benefit. These are people with proven academic reputations in various specialities, who apply those specialities to the study of piping: musicologists writing about music; historians writing about history; archaeologists writing about old instruments. I’d like to drop some more names, and review their achievements in detail [49], but rather than do that, I will pick out two general issues that confront us, when we start to look at our traditions in the new and clear sighted way which is now the ideal. |

しかし、どういうわけかシステムは機能します。

通常、コンセンサスが得られ、専門家は何を信じるべきか、何を信じてはいけないかを知っています。

そして、これらすべてに同意するのであれば、Robin

Lorimer によるピーブロックに関する

2つの論文が、1962年と1964年にエディンバラ大学発行の季刊誌 Scottish

Studies に掲載された 事は[48]、それがパイピングの歴史における画期的な

出来事であったと、私が言う理由が理解できるでしょう。内容についてはここでは何も言いません。これら

は、ピーブロックの構造の特定の側面を扱っており、私が言いたいのは、これからは、その内容に同意する

かしないかにかかわらず、これらの論文を十分に考慮すること無しに、他の誰もこの議論に有益な貢献でき

ないということです。 そしてこれこそが、私が先に投げかけた疑問に対する答えです。前世代の懐疑論者は、なぜこれほどまで に影響力を持たなかったのでしょうか? 彼らが間違っていたからではないと私は信じています。彼らが常に間違っていたわけではないと確信しています。 私が思うには、これらの意見は、バランスの取れた厳密な証拠の扱い、つまり私たちが学問や科学的方法 と呼ぶものによってコントロールされていなかったからではないでしょうか。昔の懐疑論者は自分の考えを 決め、他の誰かが反対の考えを持ったからといって、それを変えようとはしなかった。そして、少数の意見 の強い人たちが Oban Times の読者投稿欄で死に物狂いで戦っていた一方で、残りの世界の人々は仕事を続けた…。この場合は音楽を演奏して、賞を獲得するということです。 懐疑論者を悩ませたいくつかの疑問については、真の進歩を遂げることができるでしょう。 しかし、それには忍耐と様々な可能性への認識、そして何よりも弛まぬ努力が必要です。 そしてこれが私の物語の最終章につながります。 ここ 30年ほどで、専門の学者がパイピングの世界に参入し始めており、私たちはその恩恵を感じ始めています。 これらの人々は、さまざまな専門分野で学術的な評判が証明されており、その専門分野をパイピングの研究 に応用しています。音楽学者は音楽について書き、歴史学者は歴史について書き、考古学者は古い楽器につ いて書く。もっと多くの名前を挙げて、彼らの業績を詳しくレビューしたいところですが[49]、そうす るより も、現在理想とされている、新しく明確な視野に立った方法で私たちの伝統を見つめ始めたときに、私たち が直面する2つの一般的な問題点をピックアップしたいと思います。 |

| The first of these issues

is defined in the title of a book which is not

about piping, nor even primarily about Scotland,

though Scotland does figure prominently in it -

The Invention of Tradition, by Eric Hobsbawm,

published in 1983 [50]. In brief, it says that many of our old customs are not as old as we once thought; and indeed that some were started quite deliberately by people who conspired to nudge popular opinion in a certain direction. I am not sure that conspiracy theories are particularly helpful; I am however quite sure that the truth about anything is better than illusion, and the truth includes the beliefs and intentions of our forebears as well as the hare facts of what they did. To take a famous case, the poems of Ossian which James MacPherson published in 1761, and claimed to be translations from Gaelic, are now admitted by everyone to he spurious; but the climate of opinion which allowed so many people to he taken in by them was pervasive and its influence is still with us, for good as well as bad. The music which we have been enjoying tonight has come down to us in a tradition that is unbroken and as genuine as the Gaelic language itself. But if it had not been for romantic and patriotic sentiments fuelled in part by quite false imaginary history, would we still have it today? It’s a question for us all to think about. |

これらの問題点の1つ目は、1983 年に出版された Eric Hobsbawm 著『伝統の発明』

という本のタイトルで定義されています。この本はパイピングに関するものではないばかりか、主としてス

コットランドというものでもありませんが、スコットランドは顕著に登場しています [50]。 簡単に説明すると、私たちの古い習慣の多くは、かつて私たちが考えていたほど古くなく、実 際、世論を特定の方向に誘導するために陰謀を企てた人々によって意図的に始められたものもあるというこ とです。 陰謀論が特に役立つかどうかは確信がありません。しかし私は、何事についても真実は幻想よりも優れていると強く確信しており、真実には私たちの祖先の信念 や意図、そして彼らが何をしたか、という厳然たる事実が含まれています。 有名な例を挙げると、James MacPherson が 1761年に出版し、ゲール語からの翻訳であると主張したオシアンの詩は、現在では誰もが偽物だと認めています。 しかし、彼が非常に多くの人々を取り込まれる事を許した意見の風潮は広く浸透しており、その影響は良く も悪くも今でも私たちに残っています。 私たちが今夜楽しんでいる音楽は、ゲール語そのものと同じくらい、途切れることのない本物の伝統とし て私たちに伝わってきました。 しかし、もしロマンティックで愛国的な感情が、部分的にはまったく誤った想像上の歴史によって煽られることがなかったら、私たちは今日もゲール音楽を聴く ことができただろうか?これは私たち全員が考えるべき問題である。 |

| The second issue that comes

from the new learning, is that of authenticity.

Studies over the past 20-odd years have

confirmed beyond all reasonable doubt that

piobaireachd has changed as it has been handed

down from generation to generation [51,52]. What

are we to do with this knowledge? If one way of

playing is right does that mean that some other

way is wrong? There are many answers to

questions like these and it is important not to

fall into the trap of making sweeping

generalisations. But I am prepared to make, if

you like, a few policy statements. First: it seems to me self-evident that we should make every effort to rediscover anything that may have been lost. Preserving old documents, and recording oral history, is still a priority. Second: if we possibly can, we should try to recover the styles of the old masters in their entirety, not just pick out the bits which fit best into what we do today. That means learning the whole repertoire of each of our old authorities so that we can hear how their tunes and techniques fitted together. We need to hear the music of Donald MacDonald in the style of Donald MacDonald, the music of Angus MacArthur in the style of Angus MacArthur, in so far as we possibly can. Third: we must become more aware of what else was going on in the world of music at the time when our music was being composed. We are still too apt to think of piobaireachd as developing in a remote and misty world untouched by outside influence. Historians assure us that it was not so. And finally, music is a practical activity, and the real test is how well it works in practice. Many people before have realised the need to experiment with old styles of playing, but few if any of them have had the skill to do it convincingly - until now when a new generation of players is beginning to show us what the possibilities are. |

新しい学習から生じる

2番目の問題点は、真正性(オーセンティックであるかどうか)の問題です。 過去

20年以上にわたる研究により、ピーブロックが世代から世代へと受け継がれるにつれて変化してきたこと

が、合理的な疑いを超えて確認されています [51, 52]。

この知識を使って何をすればよいでしょうか?

ある演奏方法が正しい場合、他の方法が間違っているということになりますか?

このような質問には多くの答えがありますが、包括的な一般化を行う、という罠に陥らないことが重要です。

しかし、もしよろしければ、私はいくつかの方針を述べる用意があります。 第一に、私たちは失われたかもしれないものを再発見するために、あらゆる努力をすべきであることは、 自明のことだと私には思われます。 古い文書を保存し、口承の歴史を記録することは今でも優先事項です。 第二に、可能であれば、今日の活動に最も適合する部分を選択するだけでなく、古い巨匠のスタイルを完 全に復元するように努めるべきです。 それは、私たちの古い権威のそれぞれのレパートリー全体を学び、彼らの曲とテクニックがどのように組み合わされているかを、聴くことを意味します。 私たちは可能な限り、Donald MacDonald のスタイルで Donald MacDonald の音楽を、Angus MacArthur のスタイルで Angus MacArthur の音楽を、聴く必要があります。 第三に、私たちの音楽が作曲されていた当時、音楽の世界で他に何が起こっていたのかをもっと認識する 必要があります。 私たちは依然として、ピーブロックが外部の影響を受けていない遠く離れた霧の世界で発展していると考えがちです。 歴史家たちは、そうではなかったと断言します。 そして最後に、音楽は実践的な活動であり、本当のテストはそれが実際にどれだけうまく機能するかで す。 これまで多くの人が古いスタイルの演奏を実験する必要性を認識していましたが、新しい世代のプレーヤーがその可能性を私たちに示し始めている今日まで、そ れを説得力を持って行う演奏技術を持っていた人はごく僅かでした。 |

| And so, after that rather

serious note, we will finish with what we are

all really here for, which is to enjoy good

music. Allan MacDonald, again, is going to play,

and you may think the piece I have asked for is

a good choice, even a bit mischievous. At least

it’s a good title: MacLeod’s Controversy. It is a famous tune, but instead of the well known setting due to Angus MacKay, Allan is going to play the one from Colin Campbell’s manuscript, and he is going to interpret the grace notes on the basis of our earliest writer, Joseph MacDonald. Apart from that, I have, again, asked Allan to use his own judgement entirely - and here he is, Allan MacDonald, to play MacLeod’s Controversy[53]. |

それで、このかなり深刻な記述の後は、私たち全員がここにいる本当の

目的、つまり良い音楽を楽しむことで終わりにしましょう。 Allan MacDonald が再び演奏しま

す。私が頼んだ曲は、少しいたずらっぽいかもしれませんが、良い選択だと思ってもらえるでしょう。

少なくとも、MacLeod's Controversy(マクラウドの論争)というタ

イトルは良いですね。 これは有名な曲ですが、Angus MacKay に よるよく知られたセッティングの代わりに、Allan は Colin Campbell のマニュスクリプトにあるものを演奏し、初期の著述者である Joseph MacDonald の解釈に基 づいた装飾音を付加します。それとは別に、私は再び、Allan に完全に自分自身の判断を下すよう求めました。さあ、彼の登場です。Allan MacDonald が MacLeod's Controversy を演奏します[53]。 |

冒頭で、今回の講演の第4章では「学術界の専門学者たちからもたらされている、解釈に関するニューウェーブ」 について 述べられると書いてあったので、てっきり 20世紀最後の四半世紀に於ける(ご自身も含めた)民主的な専門学者の台頭時代の事を指しているだと思いました。ところがどっこい、なんと、かの Archibald Campbell, Kilberry がその最初の例として挙げられていたのには驚きました。しかし、読み終わってみれば至って納得。正に「バランスの 取れた厳密な証拠の扱い、つまり私たちが学問 や科学的方法 と呼ぶものによってコントロールされている」 解説でした。最初に書いた通りの極めて知的で冷静な Cannon 大 先生ならではです。

その上で、物語の最終章として書かれていた、「ここ 30年ほどで、専門の学者がパイピングの世界に参入し始めており、私たちはその恩恵を感じ始めています。 これらの人々は、さまざまな専門分野で学術的な評判が証明されており、その専門分野をパイピングの研究 に応用しています。音楽学者は音楽について書き、歴史学者は歴史について書き、考古学者は古い楽器につ いて書く。」 という下りが、私が想像(期待?)していた通りの記述でした。つまりは、この改革が始まったのは 20世紀後半半ば近くの1970年代に入ってから、と言う認識は間違い無かったのです。

William Donaldson による "Pipers"(New Edition/2020年/P81〜)に、これを裏付け る次の様な記述がありま した。

| Shortly

after the deaths of Archibald

Campbell and J.

P. Grant in 1963, a number of leading

professional pipers were invited to join,

including in 1964 John

MacFadyne and Seumas

MacNeill (who later became its

Honorary Scretary), Pipe-Major Donald MacLeod in 1966,

James McIntosh in

1972, R. B. Nicol

of Balmoral in 1974, and Donald

MacPherson, Iain Morrison and John Wilson of Trononto

soon afterwards. (中略) A number of academics from various subject areas were recruited in the early 1970s including Peter Cooke (ethnomusicology), Roderick Cannon (chemistry) and Professor Alex Haddow (medicine), the first two going on to exert a considerable influence on the Society’s affairs. |

Seumas と共に1964年に漸く加入が認められた John MacFadyen の提唱によって、1972年に PS カンファレンスが開催された顛末はパイプのかおり第48話で 紹介した通り。プロフェッショナル・パイパーたちと共に、積極的に加入を促した様々な分野の専門学者たちが顔を揃えた 1972年の参加者一覧からは、明らかに新時代の到来を感じさせられます。

Cannon は最後に4つの提案を掲げていますが、 その前提となる、「ピーブロックが世代から世代へと受け継がれるにつれて変化してきたこと が、合理的な疑いを超えて確認されている」事例して挙げられているのが、索引No.51 Dr. Peter Cooke "Changing Styles in Pibroch Playing" と、 索引No.52 Allan MacDonald "The relationship between pibroch and Gaelic song" だというのも至極納得。

そして、4つの提案については、その後着々と成果が挙げられつつあるのはご存知の通り。PS自体の改革も、Alt Pibroch Club の設立も、 全てはこの Cannon 大先生の1999年の講演 に於ける提案が、バックボーンとなっていたと言えましょう。正に、21世紀の到来を直前に控えて、冷静さの中にも決然と した決意が込められている《改革宣言》と言えるのではないでしょうか。

かくも高尚なレポートを前にして出てくる言葉は、次のただ一言だけです、

Dr. Cannon 本当にありが

とうございました!