第50話(2023/1)

"Dastirum"

Revisited

私をオール

ド・スタイル(※)のピーブロックに目醒めさせてくれたのは、パイプのかおり第28話(2007

年9月)で紹介した、Allan MacDonald

の "Dastirum" という

CDアルバムです。それ以来、折に触れこの貴重な演奏音源を聴いていましたが、その豪華なジャケット&ブックレットについては、最初に手にして以来、殆ど

手にする事はありませんでした。

私をオール

ド・スタイル(※)のピーブロックに目醒めさせてくれたのは、パイプのかおり第28話(2007

年9月)で紹介した、Allan MacDonald

の "Dastirum" という

CDアルバムです。それ以来、折に触れこの貴重な演奏音源を聴いていましたが、その豪華なジャケット&ブックレットについては、最初に手にして以来、殆ど

手にする事はありませんでした。※ オールドスタイル(Old Style)というと何処となく「古くて廃れた」といったイメージが付きまといがち。トラディショナル・スタイル(Traditional Style/伝統的スタイル)という方が心地良く響きます。

しかし先日、パイプのかおり第49話 のコンテンツ作成に際して、Alex J. Haddow のケルト装飾模様の鮮明な部 分画像を参照する為に、久しぶり(15年ぶり)にブックレットを紐解く機会がありました(実際にはスキャンしてデジ タル化してあるブック レットをクリックしてディスプレイに表示する、という行為ですが…)。そして、画像のピックアップ作業が終わった後 に、テキストも読み直す事に。最近はすっかり翻訳ソフト頼みが当たり前になってしまったので、PDFファイルを文字 認識可能なフォーマットに変換して翻訳ソフトに掛け、イージーに読み進めます。

そうした所、15年前に目を通した際には、実際にはそれらの解説文を殆ど読み解けていなかった事に気付かされまし た。

2007年9月というのは、私が30年前の "Piping Times" を振り返る作業を正に開始した月。それからの15年間であ れこれと知識や情報が蓄積された今日の視点で読み直してみると、同じ文章が当時とは格段に違って 深く理 解できる様になっているのです。Barnaby Brown の解説文やその他の識者たちの言葉は、Allan MacDonald による1990年以降の活動、そして、この作品が Kilberrysm が吹き荒れた20世紀のハイランド・パイプ界を浄化し、正しい方向に向かわせる嚆矢として、どれほど意義深い物であ るのかを切々と訴え掛けていると言う事が、今更ながら理解出来た次第。

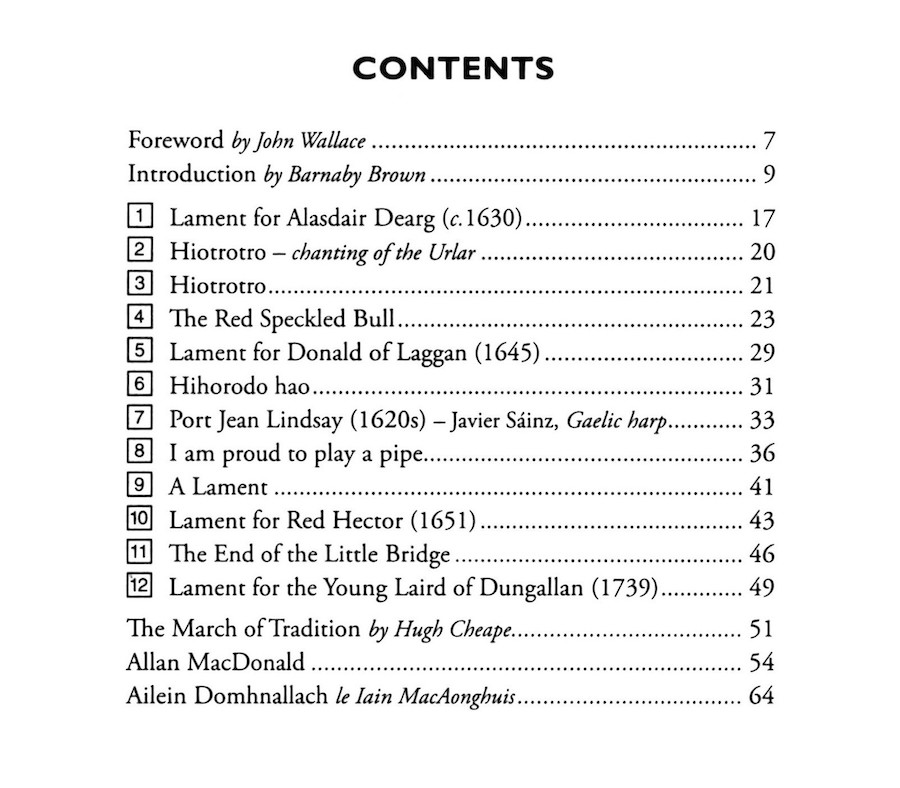

そこで、15年目にして新ためてブックレット解説文について、対訳しつつ要点について解説して いきたいと思います。オリジナルのブックレットを参照する際は↓の目次ページをクリックすると、PDFファイル(文字認識フォーマット)にリンクしていま す。

では、謝辞(Acknowledgements)と序文(Foreword)は飛ばして、まずは Barnaby Brown によるイントロダクション (Introduction)から…。

| 原 文 |

日本語訳 |

|---|---|

|

|

"This instrument produces what the Irish regard as the touchstone of fine musical sounds" Richard Stanihurst (De Rebus in Hibernia Gestis, 1584) |

「この楽器は、アイルランド人が優れた音楽音 の試金石とみなすものを生み出す。」 |

| Pibroch is like fine

wine 一 it adds a touch of class to any occasion,

attracts myth and obsession, holds secrets to

aficionados, and a small sip leaves a wonderful

feeling. In the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, pibroch roused men's courage in

battle, gathered clans when scattered,

immortalized heroes, chieftains, and great

events, and uplifted people's spirits when

feasting, marching, rowing, or harvesting.

Considered the highest form of piping (known in

Gaelic as ceol mor, the 'big music'), pibroch

carries a bouquet of superiority, dignity,

mystery, and romance. It brings to life the

late-medieval history of Ireland and Scotland

and endows Highland culture with a majestic

nobility. Yet, the bagpipe is linked in most people's minds, not with great music, but with the cliches of Scotland: kilts, massed bands, buskers, and "Scotland the Brave". The ceremonial music of the Gaelic chieftains, 1550-1750, has kept a low profile. Why is this? Opportunities to hear pibroch or have it explained to you are scarce, unless you are a Highland piper; or married to one. Its full glory is often concealed. Once discovered, however, its intricacies and delights continue unfolding for years. Like Bach's fugues, structural depth accounts both for its perennial fascination and the failure by many players to appreciate or convey what is happening in the music. But these are not the only reasons it is underestimated or overlooked by the world at large. There are also deep prejudices, at least in the UK, and an intractable lack of confidence on the part of its artists, particularly those of Highland background. Often an object of ridicule, the bagpipe is not recognized as a serious musical instrument in many schools. Competitions have dominated pibroch performance since 1781, and recitals were rare before the 1980s. The circuit of annual competitive events which now spans the globe has the positive effect of nurturing artistic companionship and technical excellence, but it has also bred cultural fundamentalism. Pibroch has been steadily institutionalized since the early nineteenth century, and the pursuit of an idealized version of the past has extinguished the variety which once clearly existed. Resistance to innovation has created new obstacles. At the premier pibroch events in 2006, the excessive periods of tuning (during which everyone talked) and appalling programming betrayed a performer culture indifferent to the audience. One heavy pibroch followed another from 9am to 5pm. No harper, singer, fiddler, professional storyteller, or even a light pibroch relieved the ear. No wonder the general public was absent. The first serious attempt to tackle this problem was a recital organized by Patrick Molard in 1992. It was in Brest, repeated in Paris, with audiences that would put Scotland to shame. There wasn't a note of tuning on stage. 1500 people showed up in Brest, 900 in Paris, and there have been regular pibroch recitals and educational events in Brittany ever since. Allan MacDonald was one of the artists, and he repeated the no-tuning-on-stage idea at the Edinburgh International Festival in 1999. People still talk about that night as the best pibroch concert in modern times. Allan set another milestone at the 2004 Festival by involving other instruments and an actor, creating four chamber-music evenings that set pibroch in its historical and cultural context. This won a Herald Angel award for its imaginative and creative approach, broadening pibroch's appeal to a mainstream audience. So why has pibroch not yet emerged from its cocoon? Yes, competition players have been desensitized to the needs of listeners and, yes, musicality has been stultified by the transfer of power from living player to printed score 一 or, more recently, archive recording. But the root of the problem lies deeper. An economic and cultural depression blighted Gaelic-speaking communities throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, exacerbated by brutal reprisals following the 1745 uprising. The structure of Gaelic society was systematically dismantled by a nervous Government ; Gaelic-speaking leaders were executed, exiled, and replaced by those more attuned to 'British' norms ; and this state-sponsored terrorism was followed by economic deprivation and population displacement on a massive scale. This has been well documented, and we are still living with the resulting brain drain away from piping and collapse of cultural confidence associated with language loss. The strength of piping today owes much to the College of Piping in Glasgow, founded in 1944, and the Piping Times, its monthly magazine since 1947. The Piobaireachd Society, founded in 1903, has also grappled with the editorial nightmare of publishing sources that are enigmatic, inconsistent, and which differ from the teaching received by oral transmission. One of the brightest developments in recent years has been the degree course launched in 1996 by the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, which has expanded in partnership with the National Piping Centre since 2000. Allan MacDonald was on the steering committee and is one of the principal tutors. An issue he constantly challenges is the lack of time or willingness on the part of competitors to risk something new, even when it has historical authority. It takes less time to go with the known, and the result for audiences is increasing boredom. As observed in the Piping Times editorial of July 2005, the interpretative convergence is stultifying : everyone sounds the same. |

ピーブロックは高級ワインのようなもので、

ど

んな場面にも気品を与え、神話や妄想を引き付け、愛好家の秘密を握り、一口飲めば素晴らしい感動を与え

てくれる。16世紀から17世紀にかけて、ピブロックは戦場で勇気を奮い立たせ、バラバラになった一

族を集め、英雄、チーフテン、偉大な出来事を不滅のものとし、祝宴、行進、ボート漕ぎ、収穫の際に人々

の精神を高揚させるものだった。ゲール語で「大きな音楽」と呼ばれるパイピングの最高峰、ピーブロック

は、優越感、威厳、神秘、ロマンスの花束を携えている。アイルランドとスコットランドの中世後期の歴

史に息づき、ハイランド文化に威厳ある高貴さを与えている。 しかし、バグパイプは多くの人々の心の中では、偉大な音楽ではなく、キルト姿、大仰なパイプバンド、 街頭芸人、「スコットランド・ザ・ブレイブ」といった スコットランドの決まり文句と結びつけられている。1550年から1750年にかけてのゲール族 のチーフテンの儀式用音楽は、あまり知られていないままだ。 それは何故だろうか? ピーブロックを聴いたり、説明してもらったりする機会は、ハイランド・パイパーか、その結婚相手でも ない限り、ほとんど無い。 そのため、ピーブロックの魅力はしばしば隠されている事が多い。 しかし、一度その魅力に気付くと、その複雑さと喜びは何年にもわたって展開される。 バッハのフーガと同様に、構造的な深さがこの曲の永遠の魅力であり、多くの奏者が音楽の中で起こっていることを理解し、伝えることができない理由でもある 。 しかし、世間で過小評価されたり、見過ごされたりする理由はそれだけでは無い。少なくとも英国 では、深い偏見と、特にハイランドの出身者の一部のアーティストには、どうしようもないほどの自信の無 さがあるのだ。バグパイプはしばしば嘲笑の対象となり、多くの学校では本格的な楽器として認識されて いない。 ピーブロックの演奏は1781年以来、コンペティションが主流であり、1980年代以前はリサイタル は稀だった。毎年開催される世界規模のコンペティションは、芸術的な交友関係や優れた技術を育むという 良い面もあるが、同時に文化的な原理主義を育むことにもなった。ピーブロックは19世紀初頭から厳格に 制度化され、理想化された過去のバージョンを追い求めるあまり、かつては明確に存在していた多様性を消 滅させてしまった。また、改革に対する抵抗が新たな障害を生んでいる。 2006年に開催されたピーブロックのプレミアイベントでは、延々と続くチューニング(その間、全員が話をしている)とゾッとする様なプログラムが、観客 に対して関心を持とうとしないパフォーマー文化にしっぺ返しをする事になる。朝9時から夕方5時まで、 重苦しいピー ブロックが延々と続く。 ハープ奏者、歌い手、フィドル奏者、プロの語り部の存在や、軽いピーブロックを選ぶ事によって観客の耳を和ませるといった工夫も無い。一般客が居ないのも 決して不思議では無い。 この課題に初めて真剣に取り組んだ例は、1992年に Patrick Molard が企画したリサイタルである。 ブレストで行われ、パリでも開催されたこのリサイタルでは、スコットランドも顔負けの聴衆が集まった。舞台上ではたったの一音もチューニングされな かった。ブレストで 1500人、パリで 900人が集まり、それ以来、ブルターニュでは定期的にピブロックのリサイタルや教育イベントが行われている。 Allan MacDonald はそれらに参加するアーティストの一人で、1999年のエジンバラ国際音楽祭でも「ノー・チューニング・オン・ステージ」のアイデアを踏襲した。その夜の ことは、現代における最高のピーブロック・コンサートとして、今でも語り継がれている。(※01) 2004年のフェスティバルでは、他の楽器と俳優を参加させ、ピーブロックを歴史的、文化的な文脈で とらえた4つの室内楽の夕べを開催し、さらなるマイルストーンを築いた。 これは、ピブロックの魅力を大勢の聴衆に広めた、想像力に富んだ創造的なアプローチとして、ヘラルド・エンジェル賞を受賞したのである。 では、なぜピーブロックは未だに繭から出てこないのだろうか? 確かに、コンペティション・プレーヤーは聴衆の求めるものに鈍感なままだし、音楽性も、生身の演奏者 から印刷された楽譜、もっと言えば最近ではアーカイヴ録音に力を移したことで矮小化されている。 しかし、この問題の根はもっと深いところにある。 18世紀から19世紀にかけて、経済的・文化的な不況がゲール語圏のコミュニティを苦しめ、1745 年の蜂起に伴う残忍な報復によって、さらに悪化させられた。ゲール語社会の骨組みは、神経質になってい た当時の政府によって組織的に解体され、ゲール語を話す指導者は処刑されたり、追放された。そして、よ り英国の規範に沿った指導 者に取って代わられた。 この国家によるテロリズムによって、大規模なスケールでの経済剥奪と人口移動が続いた。 このことはよく知られており、私たちは現在もなお、言語喪失に伴うパイピング界からの頭脳流出と文化 的自信の崩壊を引きずっているのだ。 今日のパイピング文化の力強さは、1944年にグラスゴーで設立された College of Piping(カレッジ・オブ・パイピング)と、1947年から続くその月刊誌 "Piping Times" に負うところが大きい。1903年に設立された Piobaireachd Society(ピーブロック・ソサエティー)も、不可解で一貫性のない、口承の教 えとは 異なる楽譜を出版する為に、編集上の悪夢と格闘してきた。(※02) 近年、最も目覚しい発展を遂げているのが、Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama が1996年に開始し、2000年からは National Piping Centre(ナ ショナル・パイピング・センター)と提携して拡大した学位コースである。 Allan MacDonald は運営委員会のメンバーであり、主要講師の一人である。彼が常に課題としているのは、競技者側に、たとえその曲やセッティングに歴史的な正統性があったと しても、既存の物と違った何かしら新しいものに挑戦する時間や意欲が乏しいことである。 既成概念にとらわれて、より短時間で物事を成し遂げようとすると、結果的に観客に益々飽きられる様に なる。2005年7月 の "Piping Times" のエディトリアルにあるように、ある曲の解釈をたった一つにする事は飽き飽きさせられる:どれもが、皆同じに聴こえるから。(※03) |

| Considerable

development is required before the conditions

and prospects for aspiring pipers today are as

attractive as they were in the seventeenth

century. Estate papers record how students were sent to colleges on the isles of Skye or Mull by patrons who paid their board, clothing and tuition in full, with lifetime employment and high social prestige assured for at least 30 players at any one time : no chieftain was credible without a decent piper. Today, equivalent training inevitably means running into debt, and both social status and job security as a performer are a far cry from that enjoyed by pibroch's composers. Are we a more cultured society today than the pre-Industrial Gaels? The most famous piping colleges were extinct by the 1770s, and a deterioration in training is evident in the earliest pibroch sources, none of which were produced by the teaching elite of the 1700s - the Rankins, MacArthurs, or MacCrimmons. In 1841, a distinguished judge recorded a conversation with Angus Cameron, identifying the cause of this collapse. Cameron had won the 1794 competition in Edinburgh at the age of eighteen. Like all pibroch artists born before the 1860s, his first language was Gaelic. The judge caricatured his Highland English: Though giving great praise to old rivals, and to young aspirants, he bemoaned the general decline of the art, for hie said that there was not now one single "real piper - a man who made the pipe his buisiness”, in the whole of Appin. I suggested that it was probably owing to the want of county militia regiments, for the Highland colonels used to take their pipers with them. But he eschewed this, saying that we had plenty pipers long before the militia was heard of. I then suggested the want of training. "Ay! there's a deal in that, for it does tak edication! a deal o’ edication” But then, why were they "no' edicated"? So he hit it on the very head, by saying it was the decline of chieftains, and their castle and gatherings. “Yes”, said I, “few of them live at home now”. “At hame! ou, they’re a’ deed! an’ they’re a’ pair! an’ they’re a’ English!”By 1800, the gentry in the Highlands were exclusively English-educated. Pibroch became part of a booming new industry of Highland entertainments, more about haute couture and tartan, seeing and being seen, than about music or culture. The commercial success of these shows spawned the Highland games movement, which spread across Scotland from the 1860s onward, following the expansion of the rail network. But there were cries of cultural fraudulence. In 1884, Highlanders were urged to boycott the Argylishire Gathering by the Oban Times : By 1890, the Northern Meeting was attracting 10,000 paying spectators. "The list of those present at the Balls.., read like an international 'Who's Who'. Princes, Dukes, Ducs, Marquises, Earls, Counts, Comtes, Barons... eminent Indian grandees such as the Maharaja Holkar of Indore, Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, the Maharaja Gaekwar of Baronda.” The social climate was marked by deference and servility on the part of Gaelic-speaking pipers, and the conviction that we are civilized and they are not on the part of English-speaking gentry who were the employers, judges and arbiters of all that was acceptable in pibroch. Everything the gentry did reinforced their social superiority, and the extension of their sphere of control and influence into pibroch was, paradoxically, both the hand of death and the harbinger of the renaissance we are enjoying today. What plunged pibroch into shadow is "bookish" judging : the transfer of authority from master player to printed page. In a comprehensive study of this process, William Donaldson writes : They clung to MacKay’s book and considered departure from it, even in the smallest detail, as ‘wrong’. Their formal education encouraged them to look for a fixed, original, authoritative score and they consistently failed to grasp that variety and fluidity were inherent qualities in traditional music, signs not of corruption and decay but of well-being and vitality.John MacLennan (1843-1923) witnessed the rise of this controlling impulse. He complained to the Oban Times in 1920 : The piper may have a far better setting of the tune, but he dare not play it, and his own natural abilities are curbed ; he must simply play note for note what is put before him ; he is simply a tracer or a copyist, and is not allowed to become an artiste. A culture of servile adherence or military conformity soon prevailed, with original dissenters dying off in the I 920s and subsequent challengers ostracized vindictively, particularly between the 1960s and 1980s. Fortunately, it is now recognized that there is far more to pibroch than what you hear at the competitions. Pipe Major Angus MacDonald (1938-1999) admitted, "I have learned more about pibroch since I stopped competing than I ever dreamed there was to learn". After rising to the top, conforming to the orthodox playing style, Allan MacDonald broke ranks. Since 1990, his refreshing, soulful interpretations have won the hearts of a much larger circle and helped to stimulate fresh thinking. In this he has several predecessors, but Allan's colossal musicianship and have carried the swell of discontent gathering over the twentieth century to a watershed. He embodies a new era in pibroch, one in which scholarship and tradition are cross-fertilizing each other with valuable results ; above all, one where communication with the audience comes first. Comments like "You nearly took me off my seat!" from an elderly lady in Skye gave Allan greater satisfaction than any of his prizes. What the piping world lacks more than anything else is a discerning audience of non-players一 something the current event format will never achieve. At the most prestigious competitions in Scotland, the audience rarely numbers more than forty, the Glenfiddich Championship at Blair Castle being a noble exception. In his complete recording of William Byrd's keyboard music, Davitt Moroney writes, "Appreciation (let alone affection) is difficult to acquire without direct contact with the music", and the same is true of pibroch, which is described in The New Grove Dictionary (2001) as "an esoteric repertory performed only by and for aficionados". This is accurate today, but need it remain so? The beauty of Allan's playing and the content of these pages are a bid for greater accessibility. The title Dastirum is an encouragement to artists, promoters, film makers, and patrons to help pibroch reach beyond the ghetto of the competitions. Despite its major place in Scottish history and the extraordinary love for things Highland across the globe, how often do non-pipers get the opportunity to hear our instrument's finest music? Dastirum! New listeners may find the "big music" easier to appreciate in smaller doses, framed by something more familiar or an illuminating explanation. The track notes that follow open with historical material compiled by Hugh Cheape, Allan MacDonald and myself, followed by some discussion of the music. The recording is testament to a remarkable artist at the height of his powers and offers a balanced sampling from the cellar of over 300 works. We hope it unlocks a complexity of delights that will continue unravelling for years. Each work has been refined by generations of oral transmission and boasts excellent structure, velvety overtones, and a long finish. Slainte! |

今日、パイパーを志す者にとって、17世紀

と同じように魅力的な条件と展望が得られるようになるには、相当の状況の進展が必要である。 著名なクランの家系に残された古文書には、スカイ島やマル島のパイピング・カレッジにパイピングを習 う生 徒を送ったパトロンが、食事、衣類、授業料を全額負担し、一度に少なくとも 30人のパイプ奏者に終身雇 用と高い社会的名声を保証したことが記録されている。当時 は、優秀なパイパーの居ないチーフテン は社会的信用が無かったのである。(※04) 今日、同等の訓練を受けるとなると、必然的に借金を背負うことにな り、演奏家としての社会的地位や雇用の安定は、その当時のピーブロック作曲家たちが享受したものとは程 遠いものとなってしまう。今日の私たちは、産業革命以前のゲール人よりも文化的な社会に生きていると言 えるのだろうか? 最も有名なパイピング・カレッジは1770年代には消滅。最も古いピーブロック資料には、1700年 代の教育エリートである Rankins、MacArthurs、MacCrimmons によって作られた物は見当たらず、訓練の質の劣化が見て取れる。 1841年、ある著名な審査員が Angus Cameron との会話を記録し、この崩壊の原因を突き止めた。Cameron は、1794年に18歳でエジンバラのコンペティションで優勝している。1860年代以前に生まれたす べてのピーブロック・アーティストと同様、彼の第一 言語はゲール語だった。審査員は彼のハイランド・イングリッシュを次の様に揶揄した。 彼は、昔のライバルや若い演奏家を賞賛する一方で、パイプ芸術の衰退を嘆き、Appin 地方全体で「パイピングを生業にしている本物のパイパーが一人もいなくなった」と語った。私は「それは、恐らく郡民兵連隊が欠如している為ではないだろう か?」と示唆した。ハイランドの大佐たちは、かつてパイパーたちを連れて行ったものだ。しか し、彼はこれを否定し「民兵の存在を聞くずっと以前から、我が国には沢山のパイパーたちがいた のだ。」と言いました。そこで私は「訓練が足りないのでは?」と示唆しました。「アイ、教育は 沢山されている。盛り沢山の教育が用意されている」と彼が言う。では、なぜ訓練を受けないのだ ろうか? 彼は、チーフテンの衰退、城やギャザリングが無くなったからだと言って、まさに正鵠 を射た。私は「そうだ、今は地元にいる者はほとんどいない。」と言った。彼は「地元に居な い!」 「彼らは行動する!」「彼らはイギリス人だ!」 と応えた。1800年頃までには、ハイランドの地主貴族たちは、もっぱら英国で教育を受けるようになっ た。 ピーブロックは、音楽や文化よりもオートクチュールやタータン、見ること、 見られることを重視したハイランド・エンターテインメントという新しい産業の一 翼を担うようになった。(※05)これらのショーの商業的な成功は、ハイ ランドゲーム運動を生み、鉄道網の拡張に 伴い、1860年代以降、ハイランドゲームはスコットランド全土に広まった。 しかし、これは文化的な詐術であ るとの声もあった。 1884年、『オーバン・タイムズ』紙にはハイランダーたちに対して、アーガイルシャー・ギャザリングをボイコットするよう促す次の様な記事が掲載され た: このようなショーに参加しないことで、自分たちの立 場 に目覚め、自分たちはこれからは、ロンドンからの観光客の娯楽やハイランドの領主の虚栄心を満 たすための操り人形にはされない、ということを示そう。 1890年には、Northern Meeting は1万人の観客を集めるようになった。舞踏会に出席した人々のリストは、まるで国際的な "Who's Who" のようであった。 王子の他あらゆる爵位の貴族(Dukes, Ducs, Marquises, Earls, Counts, Comtes, Barons...)、インドール王国のマハラジャ・ホールカル、ソフィア・デュリープ・シン王女、バロンダのマハラジャ・ガイクワードといったインドの 著名な大物たち。(※06) 社会情勢は、ゲール語を話すパイパーたちの服従と従順さによって特徴づけられた。英語を話す地主 貴族たちには「我々は文明人であるが、彼らはそうではない」とう確信が有り、パイパーたちの雇 用者として、ピーブロックの(演奏スタイルの)許容範囲を決定する審判者、裁定者であった。(※07) 地主貴族のすることは全て、彼らの社会的優位性を強化するものであり、彼らの支配と影響力の範囲が ピーブロックに及ぶことは、逆説的ではあるが、死の手であると同時に、今日我々が楽しんでいるルネッサ ンスの前兆でもあったのだ。 ピーブロックを影の中に押し込んだのは「楽譜集に頼る」ジャッジメント、つまりマスタープレイヤーか ら活字への権限委譲である。このプロセスを包括的に研究した William Donaldson は、次の様に書いている:(※08) 彼らは MacKay の本に固執し、たとえ小さなことでもそこから逸脱することは「間違い」だと考えていた。 彼らの正式な教育は、固定された、オリジナルの、権威ある楽譜を探すことを奨励し、多様性と流動性が伝統的な音楽に固有の性質であり、腐敗や衰退の兆候で はなく、幸福と活力の兆候であることを一貫して把握することができなかった。 John MacLennan(1843-1923) は、この支配欲求の高まりを目の当たりにしていた。彼は1920年の『オーバン・タイムズ』紙上で次 の様な苦言を呈 している(※09) パイプ奏者は、はるかに優れた曲のセッティングを知っているにも拘らず、それをあえて演奏する事はなく、彼自身の自然な能力は抑制される。彼は単に目 の前に置かれたものを一音一音演奏しなければならず、単なるトレーサーやコピーイストであり、 芸術家になることは許されない。卑屈な遵守や軍事的順応の文化がすぐに広まり、当初の反対者は1920 年代に絶滅させられ、それに続いて異議を唱えた者たちは、特に1960年代から1980年代にかけて執拗に追放された。(※10) 幸いなことに、現在ではピーブロックにはコンペティションで演奏される以上のものがあると認識されて いる。P/M Angus MacDonald (1938-1999) は「競技をやめて以来、ピーブロックについては夢にも思っていなかった ほど多くのことを学んだ。」と発言している。(※11) (現代の)オーソドックスな演奏スタイルでトップに上り詰めた Allan MacDonald は、それまでの常識を覆した。 1990年以降、彼の爽やかでソウルフルな解釈は、より多くの人々の心をつかみ、曲の新鮮な解釈を呼 び起こすのに一役買って いる。この点では、何人かの先達がいるが、Allan の驚くべき音楽性の高さと高潔さは、20世紀に集まった不満のうねりを変革の分岐点に運んだのである。 彼はピーブロックの新時代を体現し、学問と伝統が相互に肥沃化し、貴重な成果をあげている。そして、 何よりも聴衆とのコミュニケーションを第一に考えている。 あるスカイ島の老婦人からの「(あなたの演奏は)もう少しで私を席から飛び上がらせる所だった!」と い うコメントは、Allan にどんな賞よりも大きな満足感を与えてくれた。 パイピングの世界に何よりも欠けているのは、現在のイベント形式では決して実現できない、プレイヤー では無いの目の肥えた観客の存在だ。スコットランドで最も権威のある大会で、観客が 40人を超えることは殆ど無い。(※12)ブ レア城で 開 催されるグレンフィディック選手権は、崇高な例外である。 William Byrd の鍵盤音楽の全集の中で、Davitt Moroney は「味わう事(愛情はともかく)は音楽に直接触れることなしに得るのは難しい」と書いているが、ピーブ ロックについても全く同様で、ニューグローブ辞典 (2001年)では「愛好家によって、愛好家のためだけに演じられる難解なレパートリー。」と説明されて いる。これは今日でも的を得ているが、このままでよいのだろうか? Allan の演奏の美しさと、このページの内容は、ピーブロックに対してよりアクセスしやすくするための 試みなのだ。 Dastirum というタイトルは、ピーブロックがコンペティションというゲットーを超えて届くように、アーティスト、プロモーター、映画制作者、資金援助者への励ましの 言葉である。(※13) スコットランドの歴史において重要な位置を占め、世界中でハイランドの物事が非常に愛されているにも かかわらず、パイパー以外の人が私たちの楽器の最も素晴らしい音楽を聴く機会がどれほどあるのだろう か? ダスティラム 新しいリスナーは、より親しみ易く分かり易い説明によって、少ない量で「大きな音楽」をより簡単に理 解できると感じる事が出来るのでは無いだろうか。曲目解説の冒頭には、Hugh Cheape、Allan MacDonald、 そして私の3人がまとめた歴史的資料が掲載されていて、その後に曲についての考察が続いている。 この録音は、全盛期の傑出した芸術家 の証である 300を超える作品の倉庫から、バランスのとれた作品を抜き出して証明するものである。私 たちは、この録音が、今後何年にもわたって解きほぐされ続けるだろう複雑な喜びを解き放つことを望んで いる。どの作品も、何世代にもわたる口承によって洗練された優れた構造、ベルベットのような倍音、そし て長い余韻を誇っています。 乾杯! |

正直言って、今更ながら目からウロコ状態です。

15年間掛けて、徐々に徐々に霧が晴れる様に真実の姿が見えて来ていた、20世紀のハイランド・パイプ界の穢れた状況 は、何のことはない、そもそものスタート地点だった 2007年のこのアルバムのブックレットに赤裸々に解説されていました。当時一度読んで十分に理解出来なかった理由は、一つには蓄積された情報や知識が決 定的に不足していた事。言い換えると、それまでの認識と余りにも違った事が書かれていたので、鳩豆状態だったのではない でしょうか。

更に加えて痛感するのは、基本的な英語読解力の無さ。今回は、最近の常套手段としてまず翻訳ソフ ト(Deeple & Google)に掛けてから、原文と照らし合わせながら、スコットランド独特の表現や楽曲特有な用語を修正し、省略されている言葉を推測して足し ながら意訳。漸くその内容が頭に入ってくる状況でした。

次に(※)を付けた諸所の要点について…。

※01 パイプのかおり第13話「お 薦めのピーブロック音源」で紹介したアルバム、Ceol na Pioba - Music of the Pipes/Greentrax (CDTRAX5009)/2000 としてライブ音源がリリースされ ています。

※02 2007年の時点で、PS Books を「不 可解で一貫 性のない、口承の教えとは異なる楽譜」とここまで断定的に切り捨てる書き方をしていたとは驚き でした。彼が 2013年に Alt Pibroch Club(もう一つのピーブロック団体)という 名称の組織を設立するのは、至極当然の成り行きだったのが良く解りました。それにしても不思議なのは、どう やらこの事は心あるパイパーの間では自明の事だったにも拘らず、その他の人々からその様な直接的な主張が聞こえて来ない事。やはり、最も歴史が長くて権勢 を誇って来た組織に対して忖度して自主規制してしまうのでしょうか。

※03 2005年7月 の "Piping Times" の表紙には "Binneas is Boreraig" の作者 Dr. Roddy Ross がマレー半島のジャングルでパイプを吹いている姿の写真が掲載され、エディトリアルには彼の半生が紹介されています。

※04 この様な状況だったという事については、これまでも何度か読ん だ事がありましたが、ここまで詳細な内容は初めて。そのサポートの手厚さには驚かされます。パイパーが如何に重用されて いたかが良く判ります。

※05 この辺の状況については、以前紹介した岩波新書「スコットランド 歴史 を歩く」(高橋哲雄著/2004年)の内容と整合しています。

※06 つまり、ハイランド・ゲームという場は、庶民のための運動会& お祭りといったイベントでは無くて、どちらかというと、当時の英国のみならず植民地インド王国の上流国民(搾 取階級)の社交場だった訳です。ここに出てくるインド の王族たちは、ネット検索で直ぐにプロフィールがヒットします。 因みに、The Argyllshire Gathering の起源、そして始まった当時の様子はこんな感じだったとの 事。

※07 この下線部の下りは決定的な表現。15年の間に 「どうやらこうなんじゃ無いかな?」と思える様になっていた事を、ズバッと断言してくれているので、胸の支えがスッと落 ちた気がします。

その「どうやらこうなんじゃ無いかな?」と思った事について、過去に次の3件の記事を書きました。30年前の "Piping Times" シリーズの記事なので、実際に書いたのは各号発行の30年後です。

- アマチュア・ジャッジと は貴族のことなり( "Piping Times" 1985年7月号/2015年7月執筆)

- パイパーは労働者階級( "Piping Times" 1985年9月号/2015年9月執筆 )

- アマチュアとプロフェッ ショナルの溝( "Piping Times" 1989年12月号/2019年12月執筆)

※09 1920年にこの様なストレートな発言をしていたとは…。逆説 的に言えば、1910年代に Kilberrysm が本格的に本性を現し始めてまだ日が浅かった頃だからこその発言かもしれません。抑圧される側のプロフェッショナル・パ イパーたちは、その後はこの様な率直な意見すら封印せざるを得なくなったのでは無いでしょうか。

※10 ↑の答えがここに書かれていました。前段はまあ想像通りです が、後段の「特に1960年代から1980年代にかけて執拗に追放された。」の下りは衝撃的です。つま り、私がハイランド・パイプを始めた1975年当時は、正にこのトラディショナル・スタイル・パージの総仕上げの時期 だった訳で、急に妙に生々しい話として感じられる様になりました。その中で、Geroge Moss も徹底的にやり込められていたのだと思うと切なくなります。

それにしても、A.C,K. 自身は1963年に鬼籍に入っているんですが、一体全体どの様な人々がその邪悪な意思を引き継いだのでしょうか? Seumas MacNeill も含めて、その当時の多くの パイピング関係者が、カルト宗教の信者の様な集団催眠状態に罹っていたのかも知れません。

確かに、この様な状況だったとすれば、International Piper が1978年に創刊 された意味も理解できますし、創刊号に書かれていた切実な訴えも 然もありなん、といった感じがして来ます。

※11 あの名手 P/M Angus MacDonald にして極めて印象的な発言だと思います。渦中にいる間はコンペティションのバカバカしさに気付く間が無かった、と言う事なのでしょう。

※12 bugpiper さんによる「2006・スコットランド紀行」の中で、The Argyllshire Gathering のピーブロックコンペ会場の様子が次の様に描写されています。「会場はホテルのレストラン、90人ほどの椅子が用意され ていたのですが、開始時は1/3程の入り、勿論日本人は私一人でした。一番混んだ時でも半分入ったかどうか。」 正にこ の記述を現地で体感された訳です。最初に読んだ時は「ウソだろ!」と思いましたが、どうやらそれがごくごく当たり前の状 況 だった様です。

※13 "Dastirum" というゲール語の意味については、↓8番目の曲の解説部分に出てくるので、そち らを参照して下さい。

続いて各曲に関する解説部分を紹介します。出来れば別ページにオリジナルブックレット PDF版を開いて、逐次参照しな がらお読み下さい。

| 原 文 |

日本語訳 |

|---|---|

|

|

| Alasdair Dearg, or Red Alasdair

(probably because of his hair) would have become

chief of the Glengarry MacDonalds had he not

died in about 1630. This lament appears to be his sole memorial. His life and career have been obscured in conventional history because he died before his father, the unusually long-lived Donald of Laggan (1543-1645). The MacDonalds of Glengarry (from 1660 spelt MacDonell) were in dispute with the Mackenzies of Kintail over land in Lochalsh and Knoydart. The Mackenzies had been empowered by King James VI and I to squeeze the MacDonalds out, but Glengarry resisted, pursuing territorial rights forfeited to the crown in 1493. Alasdair Dearg's step-brother, Angus, achieved greater fame by being the product of Glengarry's first marriage and, in 1602, by his death in combat on one of these territorial expeditions. A portrait survives in the Museum of the Isles, Armadale (reproduced on the inside front cover), showing the beau ieale of the Gaelic warrior chieftain, conventionally described in panegyric poetry equipped with helmet, chain-mail shirt, and sword: clogaid is luireach is ciaidheamh. In the 1890s, Clan Donald historians claimed it was a portrait of Alasdair Dearg, but this is highly dubious. It was painted at least 50 years after Alasdair Dearg's death, and is largely a copy of the portrait of Lord Mungo Murray (1680s) by John Michael Wright. |

Alasdair

Dearg、または Red

Alasdair(恐らく、彼の髪の色からそう呼ばれたのだろう)は、もしも

1630年頃に死んでいなければ、Glengarry の

MacDonald一族のチーフになっていた筈だ。 このラメントは、彼の唯一の記念碑のように思える。彼の生涯と経歴は、異例の長寿を誇った父親、Donald of Laggan(1543-1645) より先に彼が死んだため、月並みな歴史上では朧げである。Glengarry の MacDonald一族(1660年以降は MacDonell と綴られる)は、Lochalsh と Knoydart の土地をめぐって Mackenzies の Kintail 一族と争っていた。Mackenzie 一族は James VI and I 世王から MacDonald一族を追い出す権限を与えられていたが、Glengarry(父親) は 抵抗し、1493年に王室に没収された領土の権 利を求めた。Alasdair Dearg の義理の兄弟である Angus は、Glengary(父 親) の最初の結婚で生まれた事と、1602年に領土 遠征の戦いで死亡したこと で、より大きな名声を獲得している。 Armadale(ス カイ島にある Clan MacDonalds の居城)の博物館にある肖像画が現 存しており(CDジャケット表紙裏に再現)、ヘルメット、鎖かたびら のシャツ、剣を装備した、賛美歌で 慣例的に描写されているゲール族の戦士族長の美しい姿が描かれている:clogaid is luireach is ciaidheamh。1890年代、Donald一族の歴史家 は、この肖像画は Alasdair Dearg のものであると主張したが、これは極めて疑わしい。この肖像画は Alasdair Dearg の死後少なくとも50年経って描かれたもので、John Michael Wright によって描かれた Lord Mungo Murray の 肖像画 (1680年代)の複製である。 |

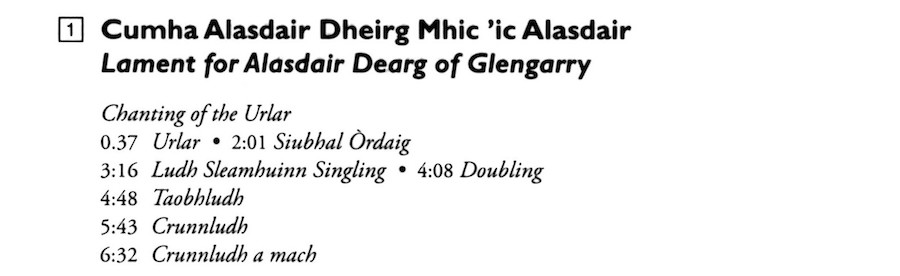

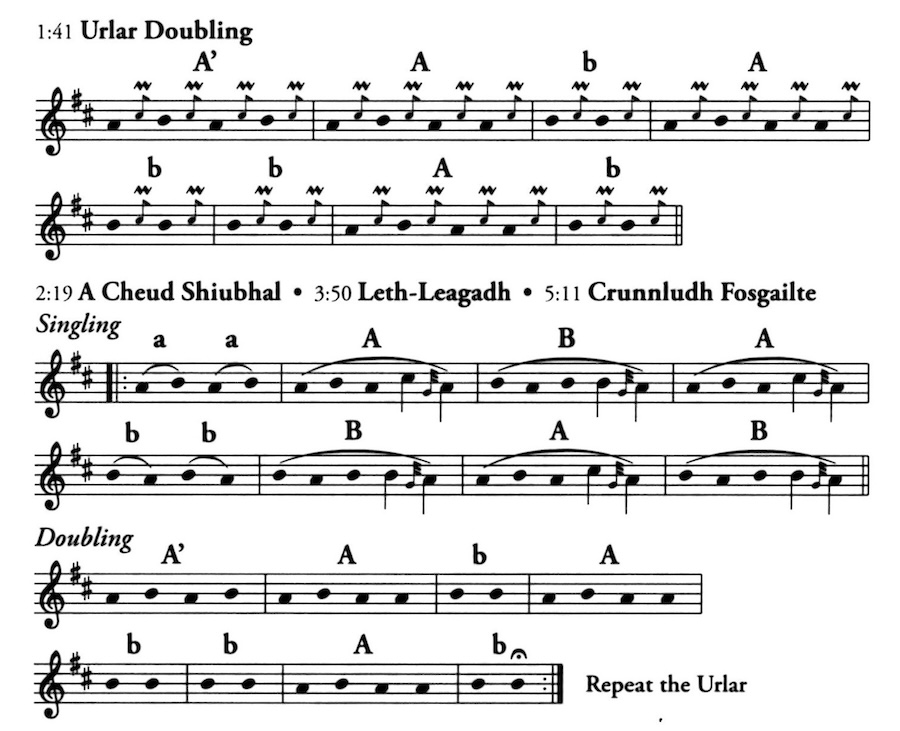

| Allan begins by

singing the Urlar, or Ground, in the

traditional way Gaels would vocalise this music

in a teaching context. When pipers began to

write down their music, after several

generations of purely oral transmission, at

least two individuals committed this canntaireachd,

or 'chanting' to paper. Their ignorance of the

staff notation used in Western music is probably

a blessing, as their texts preserve

idiosyncrasies that might otherwise have been

lost. Colin Campbell wrote out 168 works in a manuscript dated 1797, and Niel MacLeod of Gesto published 20 works in 1828. This lament is in both collections and the first Quarter oi the Urlar can be compared below. Campbell writes "two times" to indicate a repeat. At this date, the word "March" was a generic term for any pibroch. This work is an excellent introduction to pibroch structure. The music begins with a leisurely Urlar, or 'floor-plan', upon which a series of Siubhlaichean (variation sets, or 'wanderings') grows organically. Each variation is characterised by a single embellishment, reiterated with hypnotic effect. The intensity gradually increases, reaching its zenith in the Crunnludh a mach and ending with a return to the Urlar. In every pibroch, three techniques combine to create an orderly and majestic build-up of tension and drama. There is the growing complexity of the embellishments, producing a crescendo effect ; a gradual emergence from rhythmic dream-world into a trance-inducing dance ; and the distillation of a roaming melody into a more potent melodic essence. This third aspect, the reduction of the melodic line, can either be systematic 一 closely echoing the Urlar 一 or more adventurous. During the nineteenth century, however, rigid thinking narrowed the perspective of many pibroch editors. Variations that displayed structural creativity were typically assigned to an unpublishable heap or emended to correspond with the Urlar, which rendered the musical journey less exciting. Such emendations have been reversed on this recording by returning to the earliest manuscripts. In this lament, an entire 'Thumb Variation' (the Siubhal Ordaig) has been reinstated. |

Allan はまず、ゲール人が伝統

的な教えの

中でこの音楽を発声する方法で、Urlar(Ground)を歌う。数世代に渡る純粋な口承の後、パイ

パーたちが自分たちの音楽を書き留めるようになったとき、少なくとも2人の人物がこのカンタラック、つ

まりチャンティング(詠唱)を紙に書き記した。西洋音楽で使われている五線譜を知らないことは、おそら

く幸運だった。彼らのテキストは、そうでなければ失われていたかもしれない特異性を保存している。 Colin Campbell は 1797年のマニュスクリプトに168曲を書き出し、Niel MacLeod of Gesto は1828年に20曲を出版している。この Lament は両方の作品集に収録されており、最初の Urlar の1/4を以下に比較することができる。Campbell は "two times" と書いて、繰り返しを示している。この時代 "March" という単語はあらゆるピーブロックを示す総括的な用語だった。 この作品は、ピーブロックの構造を知る上で最適な入門曲である。 楽曲はゆったりとした Urlar ー フロアプラン ーで始まり、その上に一連の Siubhlaichean ー バリエーションセット、または「さすらい」ーが有機的に発展して行く。各バリエーションはある一つの装飾によって特徴付けられ、催眠的な効果で繰り返され る。その強度は徐々に増し、Crunludh a mach で頂点に達した後、Urlar に戻って終わる。 どのピーブロックでも、3つの技法が組み合わされ、緊張と劇的状況が整然と、そして荘厳に展開され る。 盛り上がり効果を生む装飾の複雑化、リズムの夢の世界からトランス状態を誘発する舞踏への緩やかな脱却、そして彷徨うメロディーをより力強いメロディーの エッセンスに抽出する。この第3の側面、旋律線の縮小は、体系的なものである場合もあれば、より冒険的 な時もある。いずれの場合も、Urlar と密接に呼応している。 しかし、19世紀には、硬直した考え方が多くのピーブロック編集者の視野を狭めた。構造的な創造性を 発揮するバリエーションは、通常、出版されない多くの堆積物の中に置かれるか、Urlar に対応するように編集されてしまい、音楽の旅をより刺激的なものにする事は無かった。この録音では、そのような編集を取り消し、最も古いマニュスクリプト に立ち返っている。このラメントでは、 'Thumb Variation' (親指バリエーション)の全体が復活されている。 |

|

|

| The business of

interpreting Campbell's notation is far from

straightforward, as it requires intimate

knowledge of the performing style of the period

and many questions remain open to debate. A fixation over minutiae in pibroch is a modern phenomenon which, like clan tartans, has its origins in the Victorian invention of a standardised tradition. For example, when singing the Urlar, Allan interchanges "himbari" and "bani", treating these as variants of the same embellishment. He does not tie himself rigidly to the score for the simple reason that, before the nineteenth century, good players reworked their material like storytellers. Allan applies such embellishments as the spirit moves him, in tune with the spirit of the age. |

Campbell

の表記法は単純明快では無いので、その解釈については、当時の演奏スタイルに精通していなければならないため、一筋縄ではいかず、論議すべき多くの疑問が

残されている。 ピーブロックの細部にこだわるのは、あくまでも現代の現象であり、クランのタータンと同様、ヴィクト リア朝の「伝統の標準化」という発明に起源がある。 例えば、Allan は Urlar を歌うとき、"himbari" と "bani" を入れ替えて、同じ装飾の変種として扱っている。彼が楽譜に縛られることが無いのは、19世紀以前の優れた演奏家は、語り部のように素材を作り変えていた というシンプルな理由からだ。Allan は、その時代のスピリットに合わせて、かつ、彼の魂が導くままにそのような装飾を施している。 |

|

|

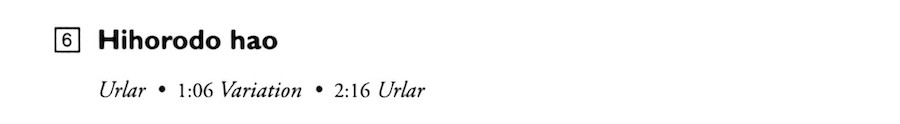

| In the same

way that some Gaelic songs are identified by the

unique syllables of refrain, rather than by the

opening line of poetry, nameless pibrochs are

identified by their opening vocables in

Campbell's notation. "Hiotrotro" corresponds to

the first three notes of this work. In the teaching of pibroch, chanting has always been considered superior to staff notation. In 1942, John MacDonald of Inverness recalled his tuition in Badenoch with Malcolm Macpherson (Calurn PIobaire, d. 1898). Macpherson was regarded as the finest player of his generation: I can see him now, with his old Jacket and leather sporran, sitting on a stool while the porridge was being brought to the boil. After breakfast he would take his barrow, cut a turf, and build up the fire with wet peat for the day. He would then sit down beside me, take away all books and pipe music, then sing in his own canntaireachd the ground and different variations of the particular piobaireachd he wish me to learn.Chanting has proved its worth in many instrumental traditions worldwide as an educational tool, as nothing surpasses the human voice for clarity when conveying a musical interpretation to a student. These chants are onomatopoeic ; in pibroch, vowels rise with pitch height, and consonant clusters immitate the embellishments. When writing it down, Colin Campbell found it was necessary to adapt the chant systematically, otherwise his text would be ambiguous (like Gesto's). He invented a notation system of high cultural sensitivity, but had to compromise the chant's beauty on the tongue in order to clarify which notes to play. The variations of this work are freer than those we generally find in the modern pibroch tradition, but this is typical of the older sources, written before rigid notions about Urlar construction set in and the urge to standardise became universal. All the Gaelic arts have been creeping into closer resonance with the Industrial English-speaking world and pibroch is no exception. Could it be that these earlier, freer settings reflect more the natural landscape of the composers, and less the regular cityscape of Victorian and Edwardian publishers? Colin Campbell used an enigmatic title, "One of the Cragich", for this and four other works, including the "Lament for Donald of Laggan" (track 5). There is nothing more rocky about these works than any others, however, so we suggest that he learnt them from a piper whose nickname was 'Cragich', possibly after the 'rocky' environment of his home, or 'rugged' features of his face. |

ゲール語の歌の一部が、詩の冒

頭部分ではなく、リフレインの固有の音節によって識別されるのと同じように、名前の無いピーブロック

は、Campbell の表記法では冒

頭の声部で識別される。"Hiotrotro" は、この作品の最初の3音に相当している。 ピーブロックの伝承では、常に五線譜よりもチャンティング(詠唱)が優れていると考えられてきた。 1942年、John MacDonald of Inverness は、Badenoch で Malcolm Macpherson(Calurn PIobaire, 1898年没)に習ったことを次の様に回想している。Macpherson はその世代で最も優れた演奏家とみなされていた。 私は今、古いジャケットにレザーのスポランをつけ、お粥が沸騰する 間、スツールに座っていた彼の姿が目に浮かぶ。 朝食後、彼は手押し車で芝を切り、その日のために湿った泥炭で火を焚き付ける。そして私の横に座り、全ての本やパイプの楽譜を片付けて、私に習わせたい特 定のピーブロックのグラウンドや様々なバリエーションを彼自身のカンタラックで歌ったものだっ た。 音楽的表現法を生徒に伝承する時、人間の声に勝るものはないという事は明らかである。そのため、チャ ンティング(詠唱)は世界中の多くの楽器の伝統的な教育ツールとして用いられており、その価値が証明さ れている。これらのチャントは擬音語である。ピーブロックに於いては、母音が音程の高さとともに上昇 し、子音群が装飾を模倣する。 Colin Campbell は、 このチャントを書き留める際、体系的に適応させなければ(Gesto のように)曖昧なテキストになってしまうことに気付いた。彼は文化的センシビリティーの高い記譜法を考 案したが、どの音を演奏するかを明確にするために、チャントの舌触りの美しさを損なわざるを得なかっ た。 この作品のバリエーションは、現代のピーブロックの伝統に見られるものよりも自由であるが、これは、 Urlar の構造に関する硬直した観念が定着し、標準化を押し進める事が普遍化する前に書かれた古い資料の典型的な例と言える。 ゲールの芸術はすべて、工業化された英語圏の世界と密接に共鳴するようになり、ピーブロックも例外で は無かった。 これらの初期の自由なセッティングは、作曲家たちが表現したかった自然の風景をより鮮明に表現してい て、ヴィクトリア朝やエドワード朝の出版社の規則正しい街並みは反映されていない、と言えるのではなか ろうか。 Colin Campbell は、"Lament for Donald of Laggan"(トラック5)を含む他の4つの曲と共に、この曲に "One of the Cragich" という謎めいたタイトルを付けている。しかし、これらの曲は他の曲と比べて特に岩っぽいというわけではない。そのため、彼はこれらの曲を 'Cragich' というニックネームを持つパイパーから学んだのではないかと考えられる。おそらく、Campbell の故郷の「岩だらけの」環 境、またはCampbell の「険し い」顔立ちにちなんで付けられたのではなかろうか。 |

|

|

| This Pibroch is attributed to

Ronald MacDonald of Morar (1662-1741), known in

Gaelic as Rghnall MacAilein Oig. He was

an aristocratic harper and fiddler as well as a

consummate piper and local hero. The "Lament for

Ronald MacDonald of Morar", one of the

highlights of the repertoire, can be heard on Donald

MacPherson - A Living Legend,

volume 1 in this series. Numerous folktales tell

of his immense strength. This one was told in 1909 by Peter McDonald, a piper living at Acharacle, just south of Moidart and Morar:

|

このピーブロックは、ゲール語で Rghnall MacAilein Oig

として知られる Ronald MacDonald of Morar

(1662-1741)

の作品とされている。彼は貴族出身のハーパー、フィドラー、また熟練したパイパーでもあり、地域の英雄だった。(ピーブロックの)レパートリーのハイライトの1つである

"Lament for Ronald MacDonald of Morar"

は、このシリーズの第1巻である "Donald

MacPherson - A Living Legend" で

聴くことができる。彼の並外れた怪力ぶりについては、数多くの民話が語り継がれている。 次の話は、Moidart と Morar のすぐ南に位置する Acharacle に住むパイ パー Peter McDonald が 1909年に語った話: Ronald MacDonald of Morar は Lochiel を訪問する途中だった。Cameron 一族は Loch Arkaig から凶暴な雄牛を捕まえて Ronald の正面を通って Sgitheal 川まで行かせた。雄牛は非常に凶暴に見えたので、Ronald は避けた方が良いと言ったが、彼の案内人は「我々が逃げたなんて彼らに言われたくな い。」と言った。そこで Ronald と雄牛は川の中で戦い合った。Ronald は雄牛を殺し、その二本の角をへし折って、案内人に持たせた。彼 は Loch Eil で1曲のピーブロックを作曲し、Achnacara 城に近づいたときに初めて演奏した。彼は帰国後、McDonald of Keppoch (in Arisaig) を訪ね、その曲を演奏した。Keppoch の領主は、この曲が自分自身への "Salute" になるかどうか尋ね、ロナルドは同意した。 |

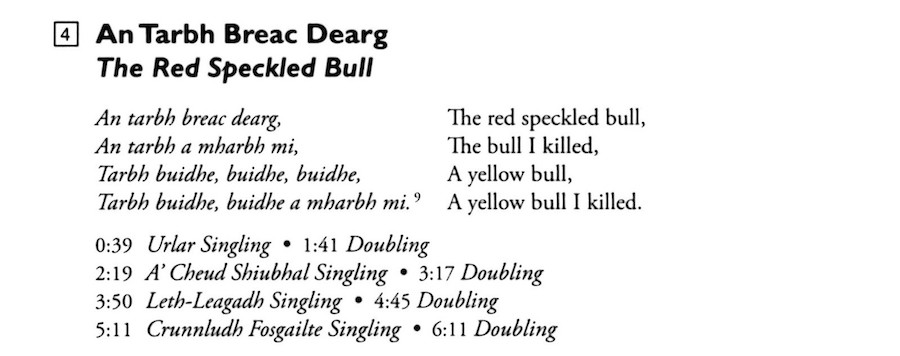

| The 'Bull' title

appears in an 1814 competition account, but when

Donald MacDonald first wrote the music down, in

1826, he called it An t-Arm Breac Dearg ("The

Red Tartaned Army"). This was the battle cry of the MacQuarries of Ulva ー an island on the west coast of Mull 一 which explains the alternative title given by General Thomason in 1905, "The Macquarries Gathering". Whether the word is Tarbh ('Bull') or t-.Ar,n ('Army'), the song associated with this pibroch sheds light on its rhythmic scansion. The positions of stresses have wandered in many tunes because pipers cannot play a note louder or quieter, only longer or shorter, or with a heavier or lighter embellishment. This can lead one to misinterpret the beat, master pipers included. As pibroch floated out of a Gaelic-speaking culture and into an English one, it gradually lost touch with the songs and canntaireachd that formerly guided its transmission. In this case, an tarbh breac dearg became an tarbh breac dearg. The stresses are clear when Allan sings it, but listening to the pipe they are much more ambiguous 一 which illustrates why the songs and chanting are so important in pibroch teaching. This work employs an Urlar design found in numerous pibrochs, including "The End of the Little Bridge" (track 11). The component phrases come in two musical flavours, alternating in a symmetrical 'Woven' pattern: |

1814年のあるコンペティションの記録に

は "Bull" のタイトルで表記されているが、Donald

MacDonald が1826年に初めてこの曲を書き留めたときには、An

t-Arm Breac Dearg("The Red Tartaned Army"

/赤いタータンの軍隊)と呼んでいた。 この曲は Ulva 島という Mull 島の西海岸にある島の Macquarries の闘いの雄叫びでもあり、1905年に General Thomason が "The Macquarries Gathering" という別のタイトルを付けたのも納得できる。 Tarbh('Bull')であろうと t-.Ar,n('Army')であろうと、このピーブロックに関する歌は、その韻律に光を当てている。バグパイプという楽器は、音を大きくしたり小さく したり、長くし たり短くしたり、装飾を重くしたり軽くしたりすることができないので、多くの曲で強拍のタイミングがず れている事が考えられる。そのため、熟達したパイパーも含めて、拍子を取り違えることがある。 ピーブロックがゲール語文化圏から漂い出て、英語文化圏に移行するに伴い、以前はピーブロックの伝承 をガイドしていた歌やカンタラックが徐々に失われて行った。 この曲のケースでは、an tarbh breac dearg が an tarbh breac dearg に変化してしまっている。強拍は、Allan が歌うとはっきり聴き取れるが、パイプで聴き取ろうとしても、ずいぶん曖昧になってしまう。これは、ピーブロックの伝承において、歌とチャンティングが如 何に重要であるかを示している。 この作品では、"The End of the Little Bridge"(トラック11)をはじめ、多くのピブロックに見られる Urlar の様式が採用されている。構成されているフレーズは2つの音楽的味わいを醸し出し、左右対称の「織り込み」パターンが交互に配置されている。 |

|

a a A B

A

b b B'

A B"

|

|

| The A flavour (or

'sonority') in "The Red Speckled Bull" contains

the same ingredients as the B flavour,

but in different proportions. B has a

spicier effect because it contains more of the

dissonant note 'B', which clashes against the

drones on 'A'. The effect is a mesmerising ebb

and flow of musical intensity. Example 1 shows

the complete procession of interweaving

sonorities, during which this 'Woven’ design is

reworked nine times. A feature of this pibroch in the earliest source is the effective way momentum is increased in the four Doublings : each phrase B is halved in length: |

"The Red Speckled Bull " の A

フレーバー(または「反響」)は B

フレーバーと同じ成分を含んでいるが、その比率は異なる。B は不協和音の

'B'を多く含むため、よりスパイシーな効果があり、'A'

上のドローンと衝突する。その結果、音楽的な強弱が変化し、魅惑的な効果が得られる。例1では、この「織り込み」デザインが9回繰り返され、織り成す音の

響きの完全な並びが表されている。 最も古い楽譜におけるこのピーブロックの特徴は、4つのダブリングで勢いを効果的に増大させることで ある。各フレーズ B の長さが半分になる。 |

| A'

A b A b b A b |

|

| Asymmetrical phrases are common

in Gaelic harp and vocal music. Their gradual

disappearance in piping is a symptom of a

changing musical landscape, hastened by the rise

of light music and pipe-band repertoire. The asymmetry in this work was eclipsed in the 1840s by Angus MacKay's manuscript, and for the following 150 years, literate pipers considered reduced phrase lengths to be 'wrong'. They were edited into uniformity in numerous works, with ponderous musical results. Another feature reinstated by Allan is the original execution of the crunnludh fosgailte. Here is the final b A b, as written by Donald MacDonald in 1826: |

非対称のフレーズはゲーリックハープや声楽によく見られるものであ

る。しかし、パイピングに於いて

は、ライトミュージックやパイプバンドの台頭により、徐々に姿を消していった。 この作品の非対称性は、1840年代に Angus MacKay のマニュスクリプトでは覆い隠され、その後150年間、楽譜の読めないパイパーにとっては、フレーズの長さを短くすることを「間違っている」と見なされ た。そして、多くの作品でフレーズの長さを統一するように指導され、音楽的に不毛な結果を招いている。 Allan によって復活したもう一つの際立った特徴は、 crunnludh fosgailte の本来の表現である。以下は、1826 年に Donald MacDonald によって書か れた最後の b A b |

|

|

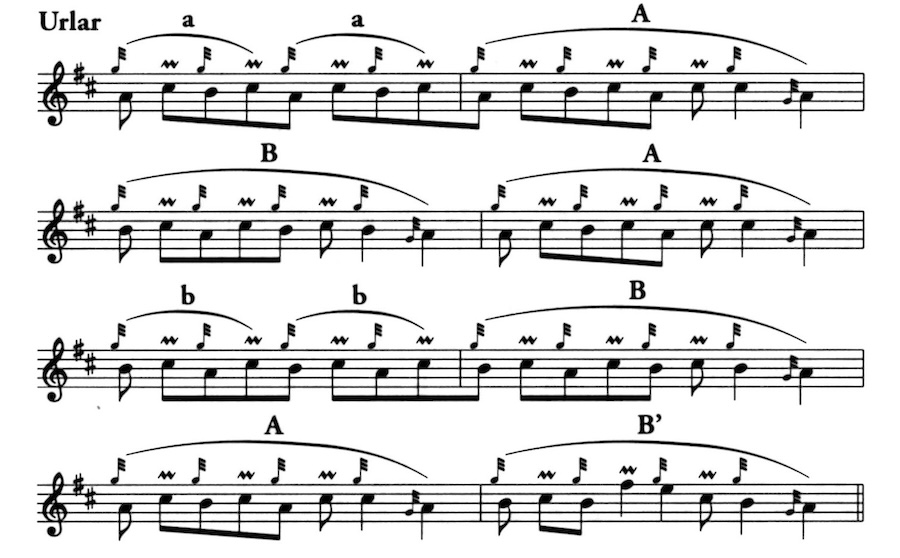

| Example 1."Tarbh

Breac Dearg"一 a score to help

listeners follow Allan's performance. A subtle

and flexible craft of timing is essential to

pibroch. The process of transcription inevitably

involves simplification, standardisation, and

interpretation by someone far removed from the

composer. Pibroch artists are trained to add an

idiomatic rubato, first learnt by ear, then

developed individually. |

例 1. "Tarbh Breac Dearg"

は、リスナーが Allan の演奏を

追えるようにするための楽譜である。ピーブロックには、タイミングを巧みにコントロールする技術が欠か

せな

い。写本を作る際の複写のプロセスには、必然的に単純化、標準化、作曲者とは縁遠い人物による勝手な解釈が含まれる。

ピーブロックの演奏者は、まず耳で覚え、その後、個別に発展させて、感情の起伏に応じて楽曲の速度を加

減する解釈を追加する訓練を受けている。 |

|

|

|

|

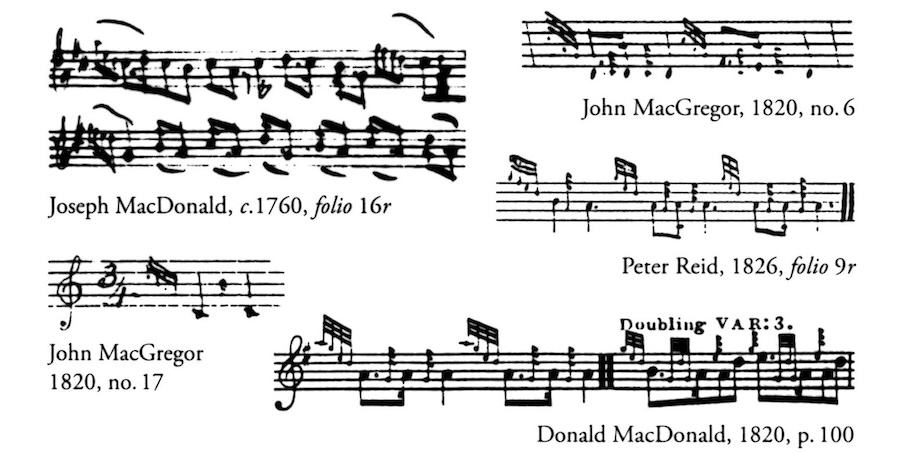

| Donald of Laggan became chief of

the MacDonalds of Glengarry in 1574. He seems

the epitomy of the late-medieval Highland clan

chieftain, his longevity offering a sort of

immortality. His pursuit of territorial rights

in the Earldom of Ross, formerly part of the

Lordship of the Isles, was opposed by leading

families such as the Mackenzies and Grants, who

were more frequently in favourwith king and

government. They took every opportunity to place

Donaldof Laggan in disrepute, and in a legal

action brought against him in Edinburgh it was

alleged that "he had a painter in Lochcarron

(which then belonged to him) painting images;

that he worshipped the image of St Coan, called

in Edinburgh Glengarry's god". These charges

reflect the religious fervor of the Covenanters,

which culminated in the "Act anent the

demolishing of Idolatrous Monuments" (1640)

ordering the destruction of all remaining

"Images of Christ, Mary and saints departed". St

Coan, an eighth-century Irish missionary, had

dedications in Lochalsh and Knoydart. Reverence

for the Irish saints of the Columban church

persisted long after the Reformation, and

Glengarry's continuing adherence to Catholic

ceremony was used by his opponents to smear his

name. Donald of Laggan died at the age of 102 on 2 February 1645, outliving his son, Alasdair Dearg, whose lament opens this disc. Donald appears on official documents as Domhnull MacAonghais mhic Alizstair, but continued to be known as Donald of Laggan because, before his succession to Glengarry, he lived at Laggan, not far from Invergarry Castle. His daughter, Iseabail Mhbr, was maid of honour to the Queen of James VI and I, Anne of Denmark. Iseabail married the 15th MacLeod chief, Sir Rory Mor of Dunvegan, and lived to the age of 103. Tradition records that for several years before her death, she was lulled to sleep every night by one of the MacCrimmon pipers, who was instructed to play her father's lament in the adjoining room. Whether this was at Dunvegan Castle or at her dower house at Scarista, Harris, remains uncertain, as is the attribution to Patrick Mor MacCrimmon. |

Donald of

Laggan は 1574年に Glengarry の MacDonald

一族のチーフとなった。彼は中世後期に於けるハイランド・クラン・チーフテンの典型であり、その長寿は一種の不死性を感じさせる。かつては

Lordship of the Isles(島々の領主権)の一部であった Earldom of

Ross(ロス伯爵領)の領土権を取り戻そうとする意思は、国王や政府からより好まれていた

Mackenzie一族や

Grant一族といった有力な一族からの抵抗を受けた。彼らはあらゆる機会を利用して Donald of Laggan の評判を落

とそう企てた。エディンバラで彼に対して起こされたある訴訟では、「彼は Lochcarron(当時

は彼の所有地)に画家を雇って像を描いている。彼はエディンバラで、Glengarry

の神と崇める聖コーアンの像を崇拝している。」と申し立てられた。これらの告発は長老派教会支持者たちの宗教的信念を反映していて、彼らのその信念は「偶

像崇拝的記念碑の破壊に対する法律」(1640年)に至り、法に基づき残存する「キリスト、マリア、亡

き聖人の像」全てを破壊するよう命じた。8世紀のアイルランド宣教師、聖コーアンは Lochalsh

と Knoydart で奉献式を行った。コルンバン教会のアイルランドの聖人に対する崇拝は宗教改革

後も長く続き、Glengarry

がカトリックの儀式に固執し続けたことは、反対者によって彼の名誉を傷つけるために利用された。 Donald of Laggan は、1645年2月2日に 102歳で死去。この CD の幕開けとなっているラメントの主人公である息子の Alasdair Dearg よりも長生きした。Donald は公式文書に於いては Domhnull MacAonghais mhic Alizstair として記載さ れているが、Glengarry を継承する前は Invergarry 城からそう遠くない Laggan に住んでいたため、その後も Donald of Laggan として知られていた。 彼の娘、Iseabail Mhbr は、 James VI & I 世王の妃でデンマーク王女 Ann の侍女であった。Iseabail は、MacLeod一族の第 15代チーフ、Sir Rory Mor of Dunvegan と結婚し、103歳まで生きた。彼女は、亡くなる前の数年間、続きの部屋で MacCrimmon のパイパーの一人に彼女の父親のラメントを演奏するよう指示し、毎晩その演奏を聴きながら眠りに着いた、と伝えられている。これが Dunvegan 城であったのか、Harris島の Scarista にあった彼女が相続した屋敷であったのかは不明であり、そのパイパーが Patrick Mor MacCrimmon だったかどうかも不明である。 |

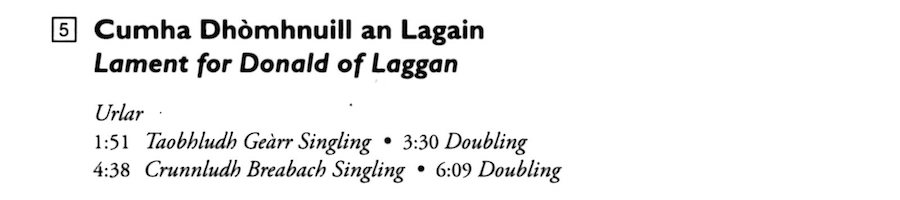

| More often than not, pibroch

variations come in pairs, and this work

exemplifies the distinction between a Singling

and a Doubling variation. In the Singlings,

each phrase ending is marked by a slowing down

and a cadential motif, whereas in the Doublings,

the figuration continues uninterrupted and at a

slightly faster tempo. On this recording, Allan interprets the earliest text, which differs substantially from the version familiar today. When Colin Campbell's 1797 setting was first published, in 1981, Roderick Cannon wrote, "To some players, it may seem like sacrilege to put forward an alternative version of such a well-known tune." Twenty-five years later, the stagnancy of the competition scene continues to discourage exploration of the unfamiliar and Campbell's version remains unknown. The work appears to have been tidied up for publication by Angus MacKay in about 1840, and a similar sanitizing process can be observed in the sources of "Lament for Alasdair Dearg" where, again, Allan brings an earlier text out of obscurity. Here, MacKay's Urlar is in suspiciously close alignment with the variations, whereas in the transcriptions by Colin Campbell and MacKay's brother, John, the musical plot is more creative : eight elastic phrases in the Urlar are transformed into seven tight breaths in the variations, producing a more dramatic crescendo effect. |

多くの場合、ピーブロックのバリエーションはペアで演奏される。この

作品はシングリングとダブリング・バリエーションの区別を示す良い例である。

シングリングでは、各フレーズの終わりはスローダウンし、カデンツのモチーフが示されるのに対し、ダブリングでは、装飾的表現はは途切れることなく、やや

速いテンポで続けられる。 この録音で Allan は、現在親 しまれているバージョンとは大きく異なる、最古のテキストのバージョンを演奏している。 1981年に Colin Campbell によるカンタラック資料の 1797年版が出版されたとき、Roderick Cannon は「ある演奏家にとっては、これほど有名な曲の別バージョンを発表することは神聖を汚す行為に思えるかもしれない。」と書いた。それから25年、コンペ ティション・シーンによる進取の精神のカケラも無い澱んだ空気は、馴染みのない曲への探究心を失わせ続 け、Campbell 版は相も変わらず世に知られないままである。 この作品は、1840年頃に Angus MacKay によって出版されるために整理されていた様で、"Lament for Alasdair Dearg" の楽譜と同様に、ここでも再び清浄化のプロセスが見受けらたので、Allan はおぼろげな中から昔の楽譜を参照した。 一方、Colin Campbell とMacKay の弟 John による楽譜化の作業では、Urlar の8つの柔軟なフレーズがバリエーションでは7つのタイトなブレスに変換され、より劇的な盛り上がり効 果が得られるなど、音楽の筋立てがより創造的になっている。 |

|

|

| This is one of the jewels of the

repertoire. With deft craftsmanship, the Urlar develops and ultimately transfigures the opening pair of phrases. Rather than limiting the music to one key, the drones are the wellspring of variety and tension in pibroch ; against their continuity, subtle melodic transformations cast successive phrases into new tonal light. In this case, the transformations are cumulative. Unassuming elements are worked up into a shapely, dramatic structure bearing the hallmarks of great composers : thematic cogency, structural control, and rhapsodic genius. It is a mistake to imagine that pibroch was cut off from the mainstream of European civilisation. The miniature 'sonata' form of this Unlar supports John Maclnnes's suggestion (page 56) that we should see the Gaelic arts in a wider European cultural context. In the age of sea-travel, the Hebrides was anything but isolated : chiefs and priests finished their education in Paris or Rome ; bardic poetry makes frequent allusion to classical Latin literature ; and chiefs, like Donald Duaghal Mackay (d.1649), were regular guests at court in Denmark, Germany, and Sweden, and might often have brought their musicians with them. "Hihorodo hao" was transcribed in 1820 by John MacGregor, principal piper to the Highland Society of London. He gave it no title, so the work is known by its opening notes as they would have been written down by Colin Campbell. MacGregor was employed by the Highland Society of London to notate pibrochs from the dictation of Angus MacArthur, then an old man and one of the most highly regarded players of his generation. MacArthur was the last in a line of hereditary pipers to Lord MacDonald of Sleat. He grew up at Hungladder, near the castle of Duntuim on the northernmost peninsula of the Isle of Skye. MacArthur accompanied Lord MacDonald to London in 1793 and was based there as part of the chief's household for the last thirty years of his life. This work is rarely performed because it does not fit the competition mould (the same is true of tracks 3 and 10). The lack of taobhludh and crunnludh variations provides a pleasant contrast to the longer works that make prize-winning tunes. Although competitions were intended to save pibroch from decline, the irony is that their single-tune format suffocates a third of the repertory. Their inexorable propagation at the expense of audience-friendly events is ultimately demeaning to the artists, and robs the general public oi a major cultural inheritance. |

この作品はピーブロック楽曲に於ける至宝の一つである。 Urlar は、冒頭の2つのフレーズを巧みな技巧で発展させ、究極的には変容させる。ドローンはその曲を一つのキーに固定するのではなく、ピーブロックの多様性とテ ンションの源泉であり、その連続性に対して、メロディーの微妙な変換が、連続するフレーズに新しい音調 の光を投げかける。 この曲の場合、変容は累積的である。 当初は慎ましい要素が、魅力的でドラマチックな構造へと鍛え上げられて行く。説得力のあるテーマ、構造の統制、叙事詩的な天才、偉大な作曲家を証明する証 である。 ピーブロックがヨーロッパの市民社会の主流から切り離されていたと考えるのは間違いである。この Unlar のミニチュア「ソナタ」形式は、ゲーリック芸術をより広いヨーロッパの文化的文脈で見るべきだという John Maclnnes の示唆(56 ページ)を裏付けるものである。 船旅の時代、ヘブリディーズ諸島は決して孤立していたわけではなかった。チーフテンや司祭はパリや ローマで教育を受け、吟遊詩人の詩は古典ラテン文学を頻繁に引用している。Donald Duaghal Mackay (1649死去) のようなチーフテンは、デンマーク、ドイツ、スウェーデンの宮廷に頻繁に招待されていて、その際にはしばしば音楽家を帯同させていた事だろう。 "Hihorodo hao" は1820年に Highland Society of London の首席パイパー John MacGregor によって書き写された。彼はこの曲にタイトルを付けなかったので、この作品は Colin Campbell が書き留めたで あろう冒頭の音節名で知られている。 MacGregor は Highland Society of London に雇われ、その世代では最も評価の高い奏者の一人だった、当時既にかなり高齢だった Angus MacArthur の口述を元に、ピーブロックの楽譜を作成した。MacArthur は Lord MacDonald of Sleat の家系に連なる最後のパイパーだった。 彼はスカイ島の最北端の半島にある Duntuim 城の近くにある Hungladder で育った。MacArthur は 1793年に Lord MacDonald に同行してロンドンに渡り、晩年の 30年間はチーフの家臣団の一人としてロンドンを拠点に活動した。 この曲はコンペティションの定型に当てはまらないため、稀にしか演奏されない(トラック3と10も同 様)。 Taobhludh と Crunnludh バリエーションが無いため、入賞曲になるような、より演奏時間の長い曲とは対照的な心地良さがある。 コンペティションはピーブロックの衰退を防ぐ事を意図して催される様になったのだが、皮肉なことに、 単一曲という形式がピーブロック楽曲の3分の1を窒息死させることになった。観客に対して親しみ易いイ ベントを犠 牲にしてまで、コンペティションを普及させることは、結局、アーティストを貶める事にな り、一般の人々から重要な文化的遺産を奪ってしまうことになるのである。 |

|

|

| Scottish harp music was

never written down by the harpers themselves,

and this port (or 'tune') was collected by a

lute player, Robert Gordon of Straloch, in the

1620s. It has been restored to its original

instrument by Javier Sainz, guided by Edward

Bunting's careful documentation of a playing

style which died out in 1807. Rev. James Kirkwood (1650-1709) summarised the Gaelic musical world as follows: The Greatest Music is Harp, Pipe, Viol [Fiddle], and Trump [jews harp]. Most part of the Gentry play on Harp. Pipers are held in great Request so that they are train'd up at the Expence of Grandees and have a portion of Land assignd and are design'd such a man's piper. Their women are good at vocal music; and inventing of Songs.It has often been concluded that pibroch is indebted to the older harp tradition, and this track illustrates one particular way pipers may have emulated the music of their respected colleagues. When Allan heard the wire-strung harp for the first time, he was immediately convinced of the likelihood of musical crossover. The ringing brass strings create a rich, drone-like effect, and the sound of each chord ー a falling arpeggio 一 made sense of one of the thorniest debates in pibroch performance practice: the interpretation of introductory runs. These were first written by pipers as follows: |

スコットランドのハープ音楽はハープ奏者自身によって書き留められた

ことはなく、このポート(または「曲」)は、1620年代に Straloch の リュート奏者 Robert Gordon

によって収集されたもの。1807年に廃れてしまった演奏スタイルに関する Edward Bunting

の詳細な記録を参照しつつ、Javier Sainz

によって元の楽器の為に復元されました。 James Kirkwood 牧師 (1650-1709)は、ゲール音楽の世界を次のように要約した。 最も偉大な音楽は、ハープ、パイプ、バイオリン(フィドル)、トランプ (口琴)だ。領主の館での演奏のほとんどはハープで行われる。パイパーは大変人気があり、雇用 主の費用で訓練され、土地の一部が割り当てられ、男性のパイパーとして育てられる。女性たちは 声楽が得意で、歌を創作する。 ピーブロックは古いハープの伝統に負っているとよく言われるが、このトラックは、パイパーが尊敬する 同胞の音楽を模倣したと思われる、ある特定の奏法を示しています。Allan は、ワイヤー弦のハープを初めて聞いたとき、それぞれの音楽の混合の可能性をすぐに確信しました。鳴り響く真鍮弦は、豊かでドローンのような効果を生み出 し、各コードの音(下降するアルペジオ)は、ピーブロックの演奏における最も厄介な論争の1つである、 導入部のランの解釈に意味を与えた。これらの導入部のランは、パイパーによって最初に次のように書かれ ている。 |

|

|

| This style of playing was

extinct by 1900, but seems to correspond with

the wire-strung harp techniques documented by

Edward Bunting in 1796: |

この演奏スタイルは 1900年までに消滅したが、1796年に Edward Bunting によって記録さ

れたワイヤー弦ハープの技法と一致している様に思われる。 |

|

|

| In this track, note how Javier

varies his timing of the falling arpeggios. The

pibroch sources show wide variation in the

timing of introductory runs; sometimes, one or

two of the ornamental notes within the run were

held longer than the others. This was a vital

technique for achieving light and shade on an

instrument that cannot change its volume. By

1900, the exception had become the rule and

pipers always held one note ('cadence E') much

longer. These cadence 'E's are often confused

with melody notes and can seriously obscure the

melody. Their original expressive effect has

been undermined through overuse and pruning them

back is one of the revolutionary features of

Allan's playing. |

このトラックでは、Javier

が下降アルペジオのタイミングをどのように変えているかに注目して欲しい。ピーブロック

の音源では、導入部のランのタイミングに幅広いバリエーションが見られる。ラン内の装飾音の1つまたは

2つが、他の音よりも長く保持されることもある。これは、音量を変えることができない楽器に於いて、陰

影(light and

shade)を表現するための重要なテクニックだった。1900年までに、ある例外がルールとなり、パイパーは常に1つの音

("カデンス E") をずっと長く保持する様になった。これらのカデンスE

は、メロディー音と混同されることが多く、メロディーを著しく不明瞭にする可能性がある。楽曲本来の表現効果は、カデンスEの過度の使用によって損なわれ

ており、これらを削減することは、Allan

の演奏の革新的な特徴の1つである。 |

|

|

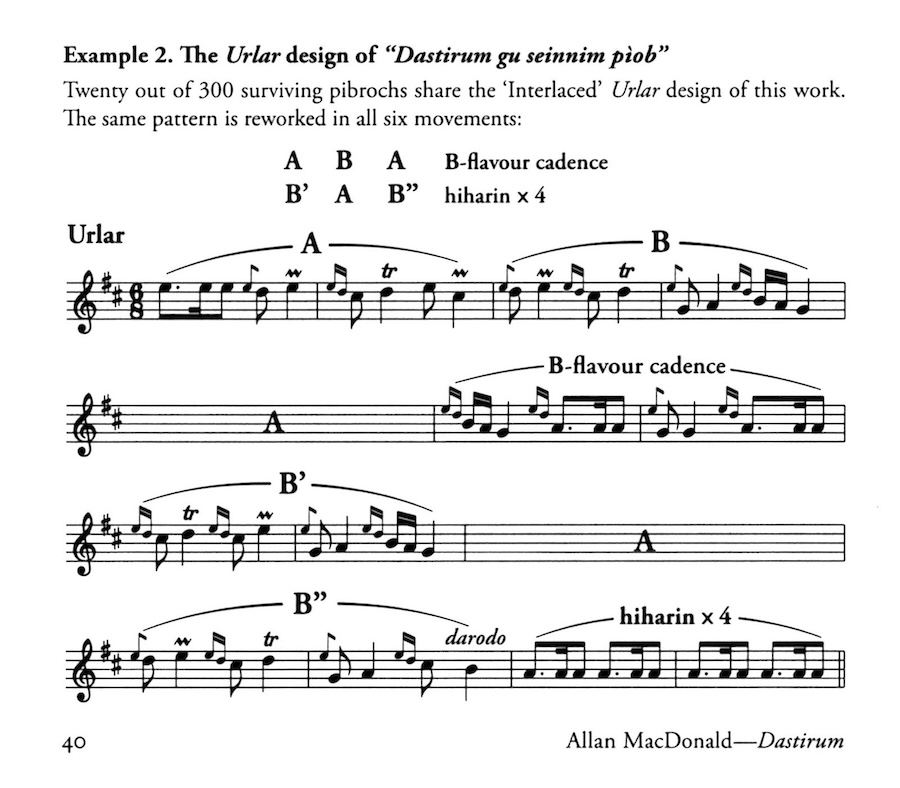

| Dastirum is now an obscure word.

It was used by Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair in a song, "Moladh Mbraig" (c. 1750 or earlier), that imitates pibroch in its structure: Dastram, dastram,In this context, it may mean 'hurray', 'bravo', or possibly 'I'd do anything for'. The pibroch title recorded by Angus MacKay is the only other known use of the word, and his translation is 'I am proud I play a pipe'. Perhaps a hint of indignation or defiance lies in the meaning of dastirum. As the Reformation took hold in the Highlands, the bagpipe became associated with Catholicism and known as the 'Papish' instument. To those attempting to civilise the natives, the pipes were a potent symbol of social disorder and banditry. Seventeenth-century efforts to enforce uniformity of tongue and manners in every corner of Britain and Ireland left cultural scars still felt today. It is in this context of repression that the title "Dastirum gu seinnim piob" perhaps makes most sense. There is an intriguing echo of plainchant in this melody. It would certainly fit the Gaelic psyche to respond to an act of ecclesiastical antagonism creatively, using the church's musical palate to reply in a defiant, mocking tone. Another possibility is that it is a rejoinder to the series of satirical songs ridiculing the pipes that begins in the early seventeenth century, when the cultural institution of learned poetry recited to harp accompaniment was overshadowed by an upwardly mobile pibroch tradition. The first and most famous of these poems is by Niall Mór, one of the MacMhuirich lineage of poets serving the MacDonalds of Clanranald. Two verses give the idea : John MacArthur’s screching bagpipeDuring Niall Mbr's lifetime (c.1550一c.1630), the rise of piping in the chief's household and declining taste for the learned poetic craft went hand in hand. Pibroch gradually became more fashionable and, by the 1650s, the bagpipe was the king of instruments. Feted like heroes, its players developed a haughty, superior attitude, remarked upon by Captain Edmund Burt in the 1720s. He describes how the chief was accompanied on formal visits, or journeys into the hills, by a retinue consisting of his foster brother, his poet, his spokesman, his sword-carrier, a man to carry him over fords, a horseman, a baggage man, "The Piper, who, being a gentleman, I should have named sooner. And lastly, The Piper’s Gilly, who carries the bagpipes". The piper's behaviour attracted further comment: In a morning, while the chief is dressing, he walks backward and forward, close under the window, without doors, playing on his bagpipe, with a most upright attitude and majestic stride. It is a proverb in Scotland, viz. ’the stately step of a piper’. When required, he plays at meals, and in a evening is divert the guests with his music, when the chief has company with him… After Culloden, the bagpipe's fall in status was rapid. By 1780, the pre-eminent MacCrimmon pipers refused to teach their own children, as piping had fallen beneath their dignity. It has taken over 200 years for Scottish society to accept the bagpipe once again as a serious musical instrument. Angus MacKay pencilled above his brother's score, "John MacKay's Favourite," probably referring to his father who was one of the greatest pipers of the early nineteenth century. As in "The Red Speckled Bull", two musical flavours are interwoven in this composition. The design is different, however, and the contrast between the two sonorities more marked. Example 2 (overleaf) shows how the 'Interlaced' design proceeds in the Urlar. The A sonority excludes the spiciest notes on the bagpipe ('B' and 'low G') unlike the B sonority, which gives them prominence. The variations follow essentially the same melody, substituting their particular embellishment and building to a climax of driving isorhythm in each Doubling. Here is the opening of the Siubhal Ordaig ('Thumb Variation'), so called because particular notes in the melody are raised to 'high A', the thumb note: This type of variation probably originates in the harp tradition. In Wales, at least, a major way of forming variations was to raise the thumb by two or three strings) |

Dastirum は今や意味不明の言葉である。 Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair が、ピーブロックの構造を模倣した "Moladh Mbraig"(1750年頃、又はそれ以前)という歌で使っていた。 Dastram, dastram,この文脈では「万歳」「ブラボー」あるいは「何でもしますよ」という意味かもしれない。Angus MacKay が記録したピーブロックのタイトルがこの単語の唯一の使用例で、彼の訳は「私はパイプを演奏することを誇りに思う」である。 おそらく、dastirum の意味には、憤りや反抗の暗示が隠されているのだろう。宗教改革がハイランド地方に定着すると、バグパイプはカトリックと結びけられて「教皇の楽器」と呼 ばれるようになった。先住民を文明化しようとする人々にとって、バグパイプは社会暴動と盗賊の激しいシ ンボルであった。 17世紀、イギリスとアイルランドの隅々まで言語とマナーの統一を強制しようとした奮闘は、今日でも 文化的な傷跡を残している。"Dastirum gu seinnim piob" というタイトルが最も大きな意味を持つのは、恐らくこのような弾圧の状況下に於いてであろう。 この旋律には、単旋律聖歌の響きがある。聖職者の敵対な行為に対して創造的に反応し、教会音楽のテイ ストを使って、反抗的であざけるような調子で応えるという行為は、確かにゲール人の精神に合っていると 言えるだろう。 もうひとつの可能性は、17世紀初頭に始まるパイプを嘲笑する一連の風刺歌への言い返しである。この 頃、ハープの伴奏で朗読する博識な詩の文化は、前途有望なピーブロックの伝統によって影が薄くなって来 ていた。 この類の詩の最初にして最も有名なものは、MacDonalds of Clanranald に仕えた MacMhuirich 系の詩人の1人である Niall Mór のものである。この2つの詩は、このような考えを示している。 John MacArthur のキーキー声のバグパ イプはNiall Mbr が生きていた時代(1550年頃〜1630年頃)には、チーフの屋敷でパイプを吹くことが増え、博識な詩の技術に対する好みが減少していった。 ピーブロックは次第により流行し、1650年代にはバグパイプが楽器の王者となった。 英雄のように祭り上げられたバグパイプ奏者たちは、高慢で人を見下した態度をとるようになる。1720年代に Captain Edmund Burt がそのことを指摘している。 彼は、チーフが公式訪問や丘陵地帯への旅に、乳兄弟、詩人、スポークスマン、剣の運び手、浅瀬を越え る際にチーフを担ぐ男、騎手、荷物持ち、そして「紳士である故にもっと早く名を出すべきパイパー、そし て最後に、バグパイプを運ぶパイパーの付き人」からなる従者を伴っていたことを描写している。 パイパーの振る舞いは、さらなるコメントを得ている。 朝、チーフが着替えをしている間、彼はドアもない窓の下を行ったり来 たりして、最大に背筋を伸ばした姿勢の堂々とした歩調でバグパイプを演奏するのだ。これはス コットランドのことわざで、「パイプ奏者の堂々たる足取り」というものだ。 求められた際には食事のときに演奏し、夜にはチーフが仲間を連れているときに、彼の音楽で客人を楽しませる。 Culloden の戦いの後、バグパイプの地位は急速に低下した。 1780年まで、MacCrimmon 家の優れたパイパーたちは、パイピングが彼らの威厳の下に落ちたとして、自分の子供たちに教えることを拒否していた。バグパイプが再び本格的な楽器として スコットランド社会に受け入れられるようになるまでには、200年以上の歳月が必要だった。 Angus MacKay は、兄弟の楽譜の上に「John MacKay の お気に入り」と鉛筆で書いた。これは、19 世紀初頭の最も偉大なパイパーの1人であった彼の父を指していると思われる。"The Red Speckled Bull" と同様に、この作品には 2 つの音楽的フレイバーが織り交ぜられている。ただし、デザインは異なり、2つの音色の対比がより顕著である。例 2 (次のページ) は、Urlar で交錯するデザインがどのように進行するかを示している。A の音色では、バグパイプの最もスパイシーな音 ('B' と 'LowG') が除外されるが、B の音色では、これらの音が目立っている。バリエイションは基本的に同じメロディーをたどり、そ れぞれの装飾音を置き換えて、各ダブリングで駆動力のある等リズムのクライマックスへと盛り上げる。 次の譜面は、Siubhal Ordaig (「親指バリエーション」) の冒頭である。メロディーの特定の音が 'High A'、つまり親指の音に上げられることから、このように呼ばれている。 このタイプのバリエーションは、おそらくハープの伝統に由来している。少なくともウェールズでは、バ リエーションを形成する主な方法は、親指を2弦または3弦上げることだった。 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In 1580, Vincenzio Galilei,

father of Galileo the astronomer, wrote that the

Irish used the bagpipe to "accompany their dead

to the grave, making such sorrowful sounds as to

invite, nay, compel the bystanders to weep."

This is the earliest reference to piping at a

Gaelic burial, but the custom is likely to be

considerably older. Over 80 laments survive, among them the most soulful and majestic melodies in the repertoire. This nameless work is a keening lament, for it begins on the highest notes of the chanter and gradually sobs its way to the bottom of the scale, breathes, and then repeats the process. This is a stylized evocation of the ritual wailing led by professional female mourners, which characterised Gaelic funerals until only recently. In both Ireland and Scotland, the English-educated ruling class found keening an abominable habit, and the church eventually succeeded in excluding women from funerals altogether. The keening tradition petered out in the 1930s in Scotland, and somewhat later in Ireland after generations of practice in secret. Rev. James Kirkwood (1650-1709) described how keening preceded and followed the piping in a funeral procession: The women make a criying while the corps is carried and when they have done, the Piper plays after the corps with his great pipe. When they come to the churchyard all the women(who always go along to Burial place)make a hideous Lamentation together and then they have their particular Mournfull Song for their other Friends that lye there.More details emerge in the letters of Captain Edmund Burt, written in the 1720s: Not long ago a Highlandman was buried here. There were few in the procession besides Highlanders in their usual garb ; and all the way before them a piper played on his bagpipe, which was hung with narrow streamers of black crape….In 1642, The Synod of Argyll expressed its distaste for this "hideous howl”: Because it is common customers in some of the remotest parts within this province of ignorant poore women to howl their head into the graves, which commonly is called the coronach, a thing unseemly to be used in any true Christian kirk.... it is ordained that every minister both in preaching and catechiseing endeavor to inform them how unseemly to Christians, and offensive to God, and scandalous to others the like practice and carriage must be.In 1666, The Synod of Armagh in Northern Ireland threatened pipers who led funerals or played at wakes with excommunication. Both practices persisted, however, and in 1689, Sir Richard Cox complained that bagpipes "are much used at Irish Burials to increase the noise and encourage the Women to Cry and follow the Corpse.” Like "Hihorodo hao", this work was transcribed in 1820 from the playing and chanting of Angus MacArthur. |

1580年、天文学者 Galileo の父 Vincenzio Galilei

は、「アイルランド人はバグパイプを使って死者を墓まで送り、傍観者を誘い、いや泣かせるような悲痛な音を出していた」と記している。

これはゲール人の埋葬でバグパイプが使われたことを示す最も古い文献だが、この習慣はかなり古くから

あったと思われる。 80曲以上のラメントが残っており、その中には最もソウルフルで荘厳なメロディーが含まれている。 この名前の無い曲は、キーニング・ラメントと呼ばれるもので、チャンターの最高音から始まり、徐々に音 階の底までむせび泣き一息つく、それを繰り返していくものである。 これは、つい最近までゲール圏に於ける葬列の特徴であった、専門の泣き女が率いる葬列の甲高い嘆き声を 様式化したものである。 アイルランドでもスコットランドでも、英語教育を受けた支配階級はキーニングを忌み嫌うようになり、 やがて教会は泣き女を葬列から完全に排除することに成功した。キーニング の伝統は、何世代にもわたって密かに行われてきたが、スコットランドでは1930年代に廃れ、アイルラ ンドでは少し遅れて廃れた。 James Kirkwood 牧師(1650-1709)は、葬列で先行したキーニングの列にパイピングが続く様子を次の様に描写している。 女性たちは隊列が運ばれている間、嘆き声をあげ続け、それが終わると、 パイパーがバグパイプを演奏する。教会の敷地に来ると、女性たち(いつも埋葬地に一緒に行って いる)は皆一緒にぞっととする様な嘆き声を発し、次に、そこに横たわる友人たちのために特別な 哀悼の歌を歌うのである。 1720年代に書かれた Edmund Burt 大尉の手紙には、さらに詳しいことが書かれている。 そう遠く無い昔、ここらでハイランド人が埋葬され時。 1642年、アーガイル教会会議 はこの "hideous howl" に対する次の様に嫌悪感を表明した。 この州の最も遠い地域のいくつかでは、無知な貧しい女性が墓に頭を突っ 込んで遠吠えをするのが一般的であり、これは一般にコロナックと呼ばれているが、真のキリスト 教教会では見苦しいものである... 説教と宗教的な指示の両方で、すべての牧師は、この種の習慣と行動がいかにキリスト教徒にとって見苦しく、神にとって不快で、他の人にとってスキャンダル であるかを知らせることに努めるよう命じられる。 1666年、北アイルランドのアーマー教会会議は、葬列を先導したり、通夜で演奏したりするパイパー たちを破門に値すると脅した。 しかし、どちらの慣習も根強く、1689年、Sir Richard Cox は、バグパイプが「アイルランドの埋葬では、騒音を大き くし、女性たちが泣き叫びながら死体に従うよう促すために多く使われている」と苦言を呈した。 この作品は、"Hihorodo hao" と同様に、1820年にAngus MacArthur の演奏とチャンティングから書き起こされたものである。 |

|

|

| There are two famous "Red

Hectors of the Battles", both Maclean

chieftains. Hector Rufus Bellicosus, the

6th chief, was killed at the Battle of Harlaw in

1411, where he was second-in-command to his

uncle, the MacDonald Lord of the Isles. This Red

Hector and his adversary, Sir Alexander Irvine

of Drum, mortally wounded each other in single

combat. Hector was buried in Iona, and

descendants of both sides commemorated the

swordfight with an annual ceremony in which

swords were exchanged. The other Red Hector, the l7th chief, was killed at the Battle of Inverkeithing in 1651. The coronation of Charles II in Perth prompted Cromwell to send a large division of his army across the Firth of Forth at Queensferry under General Lambert. When news of this reached the King's camp, General Holburne of Menstrie was sent with a cavalry regiment 1000 strong, supported by Sir Hector Maclean with 800 of his clan, the lird of Buchan with 700 men, and Sir John Brown of Fordel with 200 cavalry and two battalions of lowland foot. Here is how Maclean's official poet, Eachann Bacach, recorded the events: The news I heard on Sunday grieves me; there was no talk but of Holburne's treachery. He left Maclean on the field, fighting the battle alone, while they fled in disarray, retreat the order of the day. |

有名な "Red Hectors of the

Battles" は2人居て、どちらもMaclean一族のチーフテンである。6代目のチーフ Hector Rufus Bellicosus

は、1411年の Harlaw

の戦いで戦死した。この戦いでは、彼は叔父で Lord of the

Isles(島々の領主)であった MacDonald 一族の副官だった。この Red Hector と、その対戦相手である

Sir Alexander Irvine of

Drum は、一騎打ちで互いに致命傷を負わせた。Hector は Iona に埋葬され、双方

の子孫たちは毎年戦闘のあった日に、記念の剣闘を催し、その後それぞれの剣を交換する儀式を行なって記

念している。 もう一人の Red Hector は第17代チーフで、彼は1651年の Inverkeithing の戦いで戦死した。Perth に於いて Charles2世の戴冠式 が行われた事を受けて、Cromwell は Lambert 将軍の指揮の下、フォー ス湾を渡って Queensferry に大部隊を派遣した。この知らせが王の陣営に届くと、 Holburne of Menstrie 将 軍が1,000人の騎兵連隊を率いて派遣され、Hector Maclean 卿とそのクランマン 800人、Buchan 卿と 700 人、John Brown of Fordel 卿 とその騎兵 200人、ローランドの歩兵2個大隊が支援した。Maclean一族のお抱え詩人 Eachann Bacach は、この出来事を 次のように書き留めている : 日曜日に届いたそのニュースは私を悲しませた。Holburne の裏切りについてしか語られなかった。彼らは混乱して、Maclean を戦場に残し逃走。撤退が命じられた。 |

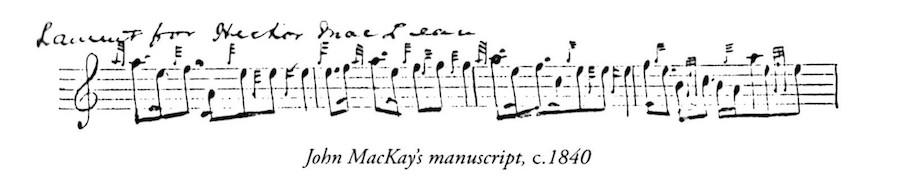

| While identification with the

17th chief seems more likely, this lament may

have been a harp piece or song celebrating the

6th chief, adapted by pipers centuries later. It was first written down in about 1840 by the brothers John and Angus MacKay. Angus later revised his score, but his original transcription corresponds with that of his brother and was chosen for this recording. John's manuscript has been neglected because many of the barlines and grace notes, and all the beams, dots, and titles, were added in about 1905 by Dr Charles Bannatyne. Fortunately, the larger melody notes written by John MacKay are unmistakable: |

(この曲が)17代

目チーフ(の武勇を讃えた曲)として認識されるのは最

ありそうな事だが、このラメントは6代目のチーフを讃えるハープ曲か歌を元に、数世紀後にパイパーに

よってアレンジされた可能性が高い。 この曲は1840年頃、John と Angus MacKay 兄弟によって初めて書き留められた。Angus は 後に楽譜を改訂したが、彼のオリジナルの楽譜は兄のものと一致していて、今回の録音はそれに基づいてい る。John のマニュスクリプトは、1905年頃に Dr Charles Bannatyne に よって、多くのバーラインと装飾音、そして全てのビーム、ドット、タイトルが追加されたため、顧みられ ることがなかった。幸いなことに、John MacKay の書いた大きなメロディー・ノートは見逃しようが無い。 |

|

|

| This is a prime example of

battle music, possibly the oldest genre of

Gaelic piping. In a manuscript written in

Ireland in the 1480s, the hero Fierabras is

advised to sound the pipes (piba) as he lays

siege to a castle. In reporting the Battle of

Flodden (1513), an English poet described the

Scots army "with their shrill pipes: Heavenly

was their melody: their Mirth to heare" And in 1580, Vincentio Galilei wrote:

The antiquity of this

particular battle tune is suggested in the

manuscript "Traditions of the Western Isles",

compiled in Stornoway by Donald Morrison in

the 1820s. He states that Donald Cam, chief of

the MacAulays of Lewis, took part in an

expedition to Ireland during which he was the

victor in a single combat with "the great

McBane"一a champion of the opposing army.

Morrison writes, "there was a song composed in

honour of this victory一the song is Cean na

Drochaid, or the Head of the Bridge".

William Matheson points out that Donald Cam is on record in 1610, and suggests that the tradition refers to the expedition in 1594 of an army of Islesmen to aid Red Hugh O'Donnell in his rebellion against Queen Elizabeth I. Other pibrochs that arose from this campaign are "Lament for Hugh", "Lament for Samuel", and later the "Lament for the Earl of Antrim". Curiously, a Victorian obelisk on the bridge in Golspie, Sutherland, bears the inscription: Mor-fhear Chatt do cheann na drochaide bige - gairm clan Chattich nam huadh (The Chatt chief to the end of the little bridge - war cry of the victorious clan Chattan). A gairm was shouted before charging into battle, sending a wave of courage through the warriors. Although there was no bridge on this site before 1810, and the obelisk looks even later, it seems unlikely that anyone would invent this gairm. It probably refers to a historic event, possibly the same 1594 expedition. On more solid ground, we have a note written by Niel MacLeod of Gesto based on information from one of the last hereditary pipers to MacLeod of MacLeod, lain Dubh MacCrimmon (c.1731-c.1822): Played by MacLed's piper, inviting the Clan Cameron to follow him and his party across the bridge to attack the enemy, which the Camerons did, during a rebelion in Ireland; and, as far as l can understad, it was in King William the Third's time (1689-1702). MacLeod of MacLeod calls the tune his gathering or battle tune, and the Camerons call it their gathering or battle tune, and from the account given to me of it, they seems to have equal right to it, with this defference, that it was played by MacLeod's piper at the head of his party, inviting the Cameron to follow and join themThis story was in circulation by 1785, when the title "Cean Drochaid Beg - Head of the Little Bridge, or the Cameron's Gathering" appeared on a poster for a competition in Edinburgh. In Colin Campbell's manuscript, however, these titles belong to different, albeit similar, compositions. Did two works become fused over time? More likely, one work divided into variants later distinguished as separate compositions. At least five works in Campbell's manuscript could be described as close relatives of "The End of the Little Bridge”. This recycling of phrases occurs in all orally-transmitted heritage, a phenomenon termed 'centonisation'. In common with Homeric poetry, Gregorian chant, and many books of the Bible, pibroch enjoyed centuries of creative fluidity before crystallising in authoritative editions. As literacy levels rose, the power and prestige of storytellers, church singers, pipers, and priests as the sources of knowledge in the Western world gradually transferred to the book. In pibroch, as in plainchant, this caused the birth of rigidity and undermined the skill of extemporaneous composition, for which this constellation of works is prime evidence |

これは戦闘曲の代表的な例であり、おそらくゲール・パイピングの最も

古い部類である。1480 年代にアイルランドで書かれたあるマニュスクリプトには、英雄 Fierabras が城を包囲する時、パイプ

(piba) を奏でる様に促された、と書かれている。Flodden の戦い (1513年)

の記録で、あるイギリスの詩人はスコットランド軍の様子を「甲高いパイプの音色。彼らの旋律は楽しげで、彼らの陽気さが伝る。」と描写しています。 そして、1580年に Vincentio Galilei は次のように書き記している。 この楽器の使用はアイルランド人の間で広く行われており、その音に合わ せて、不敗の勇士たちが遠征に出撃し、戦いの最中に互いに勇敢な行動を奨励し合う。この戦闘曲の古さは、Donald Morrison が 1820 年代に Stornoway で編纂した「西部諸島の伝統」というマニュスクリプトで示唆されている。Morrison は、Lewis 島の MacAulay 一族のチーフ、Donald Cam がアイルランド遠征に参加し、敵軍の勇士 "偉大な McBane" との一騎打ちで勝利したと述べている。Morrison は、「この勝利を記念して作曲された歌がある。その歌は "Head of the Bridge" という意味の "Cean na Drochaid", だ。」 と、記している。 William Matheson は、Donald Cam が 1610年に記録に残っていることを指摘し、その伝承からは1594 年に女王 Elizabeth I 世に対する反乱を起こ した Red Hugh O'Donnell を支援するために、島々のクランたちが行った遠征を指しているのではないかと示唆している。この遠征か ら生まれた他のピーブロックには、"Lament for Hugh", "Lament for Samuel"、そして後に "Lament for the Earl of Antrim" がある。 興味深いことに、Sutherland の Golspie にある橋の上のビクトリア朝の記念碑には、"Mor-fhear Chatt do cheann na drochaide bige - gairm clan Chattich nam huadh" (小さな橋の端にいる Chatt 一族のチーフ ー 勝利した Chattan 一族の雄叫び)という碑文が刻まれている。"gairm" は 戦の際、突撃する前に叫んで、戦士たちに勇気の波を送る叫声。1810年以前にはこの場所に橋はなく、 記念碑はさらに後世の作のように見えるが、誰かがこの "gairm" を発明したと は考えにくい。これはおそらく歴史的な出来事、おそらく同じ1594年の遠征を指しているのだろう。 より確かな根拠として、MacLeod of MacLeod の最後の世襲パイパーの一人、lain Dubh MacCrimmon(1731 年頃〜1822年頃)の情報に基づいて、Niel MacLeod of Gesto が書いた次の様な記述がある。 MacLeod 一族のパイパーが演奏し、Cameron一族に橋を渡って敵を攻撃するよう求め、Cameron一族はアイルランドの反乱の際に実際に攻撃した。私の理解 する限りでは、William3世王(1689年〜1702年)の時代だった。MacLeod of MacLeod は この曲をギャザリング曲或いは戦闘曲と呼び、Cameron一族もまた、ギャザリング曲或いは 戦闘曲と呼んでいた。私に伝えられた話によると、彼らはこの曲を同等に権利を持っているようだ が、違いは、この曲は MacLeod一族のパイパーが一族の先頭で演奏し、Cameron一族に続いて合流するよう誘ったという点だ。この物語は1785年には流布しており、エディンバラで行われたコン ペティションのポスターに "Cean Drochaid Beg - Head of the Little Bridge, or the Cameron's Gathering" というタイトルで掲載されていた。 しかし、Colin Campbell のマニュスクリプトでは、これらのタイトルは、似ているとはいえ、別の曲に付けられている。2つの作品 は、時間の経過とともに融合したのだろうか。よりあり得そうな事は、1つの作品がバリエーションに分か れ、後に別作品として区別された可能性が高い。Campbell のマニュスクリプトでは、少なくとも5つの作品が "The End of the Little Bridge” の類似曲と言える。 このようなフレーズの再利用は、口頭で伝えられる文化遺産には必ず起こりる「セントニゼーション」と 呼ばれる現象である。ホメロス詩、グレゴリオ聖歌、聖書の多くの書物と同様に、ピーブロックは何世紀に もわたって創造的な流動性を保ち、やがて権威ある版として確立していった。 識字率が高まるにつれ、西欧世界における知識の源泉としての語り部、教会の歌い手、パイパー、司祭の 権力と名声は、次第に書物に移っていった。ピーブロックでは、短旋律聖歌と同様に、このことが硬直化を 招き、即興的な作曲の技量を低下させた。このアルバムに収録されているこれらの作品群が、その最も明ら かな証拠である。 |

|

|

| There were three lairds of

Dungallan, but only one who died young: John

Cameron, the second laird, who was in his 20s

when he died in 1739. This lament is almost

certainly his, and the song associated with it

could express concern for John's health when he

inherited the Dungallan estate as a child in

1719. Allan sings two versions of the song: the

first is from a manuscript by Angus Fraser

(d.1874), the second, from Angus MacKay's book

of 1838. Archibald Cameron, the first laird, and his elder brother, Allan of Glendessary, each married daughters of Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel, and thereby became the leading men of clan Cameron, next to the chief. The small estate of Dungallan was part of the lands of Glendessary. It took its name from a ruined fort on a tidal island on Loch Sunart, which opens out to the Sound of Mull on the southerly side of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. The family seat was at Glenahurrich The young laird's lament survives in four independent sources, each with its own distinctive characteristics 一 evidence of master players making the work their own in the days before mass-produced texts and bookish judging curbed pibroch players' creativity. In this recording, Allan follows Angus MacKay's book, leaving his personal mark in the timing of A' Cheud Shiubhal, (The First Motion). Although MacKay calls it a "Salute", earlier sources agree it is a lament: In handwritten notes recently discovered by Roderick Cannon, Gesto offers more background: Mac mhic Thormoid (son of the son of Norman) is Gesto's own patronymic. It appears lain Dubh MacCrimmon told him that this lament was traditionally played at MacLeod of Gesto's funeral. If this is accurate, then the work was in circulation before the Dungallan song and title became attached to it. This conclusion is supported by the fact that, in 1820, Angus MacArthur, Lord MacDonald's piper, could not remember the work's title at all. |

Dungallan 領地には3人の領主が居たが、若くして亡くなっ

たのは1人だけだ。2代目の領主 John

Cameron は

1739年に20代で死去した。このラメントはほぼ間違いなく彼のものであり、この件に関連する歌は、1719年に John が幼子として Dungallan

領地を相続した時の健康問題を懸念していたことを表している可能性がある。Allan

はこの歌の2つのバージョンを歌っている。最初のバージョンは Angus Fraser (1874 年没)

のマニュスクリプトから、2番目のバージョンは Angus

MacKay による1838年の楽譜集からである。 初代領主 Archibald Cameron と彼の兄である Allan of Glendessary は、それぞれ Ewen Cameron of Lochiel 卿の娘と結婚し、それによって Cameron一族のチーフに次ぐ指導者となった。Dungallan という小さな領地は Glendessary の土地の一部であった。その名は、 Ardnamurchan 半島の南側、Mull 海峡に面した Loch Sunart の潮汐島にあった廃墟となった砦に由来する。一族の居城は Glenahurrich にあった。 この作品は4つの独立した楽譜に残されており、それぞれが明確に独自 の特徴をもっている。つまりそれは、ピーブロック奏者の創造性を奪い取る、大量生産された楽譜集や楽譜に固執したジャッジされる以前には、熟達したプレイ ヤーたちが個々に、個々の作品をそれぞれ独自の解釈で表現していた証拠である。 この録音で Allan は Angus Mackay の楽譜集に従ってい るが、A' Cheud Shiubhal, (The First Motion)のタイミングに Allan 自身の足跡(解釈)を記している。MacKay はこの曲を "Salute" と呼んでいるが、それ以前の資料ではこの曲は "Lament" であるとされている。 Roderick Cannon がつ い最近発見した手書きのメモの中で、Gesto は さらに詳しい背景に触れている。 Mac mhic Thormoid (son of the son of Norman)は Gesto 自身 の父称である。Lain Dubh MacCrimmon によると、このラメントは MacLeod of Gesto の葬儀で伝 統に則って演奏されたようである。もしこれが正確な ら、この作品は Dungallan の歌とタイトルが付く前に流布していたことになる。この結論は、1820年に Lord MacDonald のパイパーであ る Angus MacArthur が、この作品のタイトルを全く覚えていなかったという事実からも裏付けられる。 |

楽曲解説に続く識者による文章にも、随所に印象的な記述が見受けられ、どれも外せません。 全文を対訳で紹介します。

| 原 文 |

日本語訳 |

|---|---|

|

|

| Awealth and variety

of music and one of the most powerful and

successful of wind instruments are among

Scotland's familiar and celebrated attributes.

This cultural success story, the bagpipe, has

been played in Scotland for most of six hundred